'Bodies and blood': Libya war exacts heavy psychological toll on civilians and fighters

On a hot and dusty afternoon behind southern Tripoli’s fluid battlefront, adrenaline-filled fighters with mismatched clothes and battered weapons are either heading to or returning from the barrage of gunfire, mortar rounds, and air strikes that have lasted for over a month.

“Every night we are under air strikes,” says Ali breathlessly.

He is a 22-year-old fighter from the coastal town of Zawiyah, and part of the loose military coalition from across western Libya that has united to defeat an offensive by eastern commander Khalifa Haftar.

That morning, as they pushed their opponents back, Ali says, they found corpses of sub-Saharan migrants on a farm, and encountered wounded residents who had refused to flee their homes, along with burning buildings.

'We wish the war was over so we can live in peace'

- Lutfi, a former naval official

“They are using everything on us,” he tells Middle East Eye, as the wreckage of a plastics factory smoulders behind him.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Young men like Ali are the first line of defence of Tripoli and the internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) under Prime Minister Fayez Serraj.

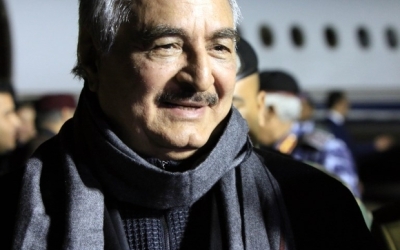

They are fighting against Haftar, a former general under Muammar Gaddafi, and his self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA).

While the numbers of combatants on either side are estimated to be roughly equal, it’s the LNA’s newly imported firepower - breaking the UN arms embargo in Libya - that has proved to be formidable.

Haftar launched a surprise attack for control of Tripoli on 5 April, interrupting the visit of the UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres and efforts to bolster the national political process.

This is the latest in battles for power and wealth that have convulsed Libya since the overthrow of Gaddafi's rule in 2011.

Lost friends

According to the World Health Organisation, more than 430 fighters and civilians have been killed in Tripoli so far, with over 6,000 people wounded and more than 50,000 residents forced to flee their homes in the suburbs.

But the psychological damage for fighters and civilians is harder to trace.

Many have been casualties and displaced, whether now, or during the fight between militias for Tripoli international airport in 2014, or in repeated conflicts around oil infrastructure and military bases in Libya’s centre, south and west, as well as from the devastating wars in Benghazi and Derna, and the brutal fight against Islamic State (IS) group militants from Sirte in 2016.

Many fighters on the current Tripoli frontline have survived violence while losing friends in the battle with IS for Sirte.

'Living nightmare'

For civilians, the death of family members, loss of property, and years of living under the thumb of heavily armed groups have taken a heavy toll.

“During clashes, when fighters are high on adrenaline, they don’t see it,” says Tripoli psychosocial counsellor Khalid Hamidi.

“It’s afterwards, when they are sitting at home – they may have flashes of a friend killed, bodies and blood. This can become a living nightmare,” he tells MEE.

Hamidi reports that some surround themselves with friends to block out violent memories.

Others resort to self-medication, using illicit alcohol or drugs from dealers, like the popular painkiller Tramadol, to erase anxiety.

This means, he says: “They can easily get into trouble. They just bring out their weapons and start shooting.”

Hamidi, a frontline responder who provides emergency psychological first aid, spent months counselling fighters after the Sirte fight was won.

“They found it difficult to return to normal life,” he remembers.

“They wanted action, not to wake up, go to a local cafe and play cards. This was boring. They needed psychological help – which didn’t happen then, and now it will be the same.”

'People turn to drugs and criminal behaviour'

Ali Abusetta, a Misrata municipality member who campaigns for psychological treatment to be taken seriously, agrees.

“We feel a great responsibility for the revolution to succeed,” he tells MEE.

“But because of successive wars and those exposed to constant psychological fear, people turn to drugs and criminal behaviour.

"This has affected marriages, poor social relations and weakens the social fabric of our town.”

At a school building in Tripoli, now housing those displaced in the fighting, Sabah, a middle-aged woman, starts to cry.

She, her husband Lutfi and their diabetic child, ran to the shelter on foot, and like many families, this is not the first time they’ve been uprooted by conflict.

Lutfi, a former Navy official, says when their electricity and water were cut, and gunfire and bomb explosions surrounded them, they panicked.

“We wish the war was over so we can live in peace,” Lutfi says.

But they had just heard from a guard left behind that their home had been looted and it was unclear what they would find on their return.

People react to the extreme danger that the fighting presents by fleeing, explains Hamidi.

“It's only when they get to a safe place that they start fretting about their property, and what will happen to it.

"Often the father will stay behind to guard it, and they worry he will be killed. This creates extreme stress.”

Children, on the other hand, are often more resilient and need activities to keep them busy.

Kidnapping and torture

While wars have torn up lives and homes, Libyans have also had to cope with daily life under a divided government, with war and stringent military rule in the east, and brutal and corrupt militias in the west.

As weapons flooded the streets after the 2011 revolution, militias proliferated, enriched by the weak Libyan currency for dummy business deals, property grabs, kidnappings and a monopoly over the smuggling of illicit goods.

While Benghazi was embroiled in war, for those in Tripoli the lack of readily available cash, decrepit services, and a constant threat of violence - including the widespread practice of kidnapping and torture - terrorised the civilian population.

When the UN-backed GNA arrived in 2016, they only exacerbated militia rule, by paying dominant armed groups to ensure their safety.

'We try to earn trust so people will talk, help them through anxiety, and let them know they are not alone'

- Safinaz al-Baz, a Tripoli-based counsellor

One Tripoli business owner, Mustafa Mohamed, 27, found himself and his cousin hijacked along the road to their farm by armed men, whom they recognised as old schoolmates.

They were tied up, thrown into the trunk of a car, and held in a house for ten days under severe duress.

“It was a bad place,” Mohamed tells MEE. “A dirty room, with blood on the floor.”

He describes how they beat him while holding up a telephone for his father to hear his cries, and asked for a ransom.

Handcuffed, without food or drink, Mohamed says he was forced to drink his own urine.

After the money was paid, he says, he flew to Egypt to recuperate for four months.

He then heard criminals attacked his father too. “We have nothing now. They stole everything,” he says.

'We’ve got to do something good for our country'

Safinaz al-Baz, a Tripoli-based counsellor with a local organisation, the Psychosocial Support Team, has spent years counselling grief-stricken families as well as victims of domestic violence, and fighters.

For her, finding a way to comfort a mother during the three-year-long kidnap and ultimate killing of her three young children in western Libya was extremely challenging.

She has remained in touch with the family ever since.

“We try to earn trust so people will talk, help them through anxiety, and let them know they are not alone,” she says.

While the dominance of a few large militias in the capital has contributed to a crackdown in small-time criminals, many of Libya’s university-age youth, whose schools are shut down again because of the fighting, and see little opportunity for jobs, just want to leave.

But they are hobbled by few opportunities to get visas and study abroad.

In a crowded Martyr’s Square in central Tripoli, Anas Mohamed, 18, is despondent.

“Haftar is a dictator - we need freedom of speech and a civil society. But the militias aren’t good either,” he says.

“We need to get rid of Haftar first, and then the militias. We’ve got to do something good for our country.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.