What the latest secret government file tells us about UK Middle East policy

The British government is refusing to release a 1941 file on Palestine, as it might “undermine the security” of Britain and its citizens.

Why would a 78-year-old document be seen as so sensitive in 2019? One plausible reason is that it could embarrass the British government in its relations with Israel and Iraq, and may concern a long but hidden theme in British foreign policy: creating false pretexts for military intervention.

The Colonial Office document, at the National Archives in London, was uncovered by journalist Tom Suarez and concerns the “activities of the Grand Mufti [Haj Amin al-Husseini] of Jerusalem” in 1940-41.

After the assassination of Lewis Andrews, British district commissioner for Galilee, in September 1937, the British Government dismissed al-Husseini from his post as president of the Supreme Muslim Council and decided to arrest all members of the Arab Higher Committee, including Husseini.

He took refuge in the Noble Sanctuary (al-Haram al-Sharif), fled to Jaffa and then Lebanon, and ended up in Iraq, where he played a role in the Iraqi national anti-British movement.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

He spent the Second World War moving between Berlin and Rome and took part in the propaganda war against Britain and France through Arabic radio broadcasts.

A plan ‘to clip the mufti’s wings’

In April 1941, nationalist army officers known as the Golden Square staged a coup in Iraq, overthrowing the pro-British regime, and signalled they were prepared to work with German and Italian intelligence. In response, the British embarked on a military campaign and eventually crushed the coup leaders two months later.

But Suarez discovered in the files that the British were already wanting such a “military occupation of Iraq” by November 1940 - well before the Golden Square coup gave them a pretext for doing so.

The reason was that Britain wanted to end “the mufti’s intrigues with the Italians”. One file notes: “We may be able to clip the mufti’s wings when we can get a new government in Iraq. FO [Foreign Office] are working on this.” Suarez notes that a prominent thread in the British archive is: “How to effect a British coup without further alienating ‘the Arab world’ in the midst of the war, beyond what the empowering of Zionism had already done.”

There have long been claims that these riots were either condoned or even orchestrated by the British to blacken the nationalist regime

As British troops closed in on Baghdad, a violent anti-Jewish pogrom rocked the city, killing more than 180 Jewish Iraqis and destroying the homes of hundreds of members of the Jewish community who had lived in Iraq for centuries. The Farhud (violent dispossession) has been described as the Iraqi Jews’ Kristallnacht, the brutal pogrom against Jews carried out in Nazi Germany three years earlier.

There have long been claims that these riots were condoned or even orchestrated by the British to blacken the nationalist regime and justify Britain’s return to power in Baghdad and ongoing military occupation of Iraq.

Historian Tony Rocca noted: “To Britain’s shame, the army was stood down. Sir Kinahan Cornwallis, Britain’s ambassador in Baghdad, for reasons of his own, held our forces at bay in direct insubordination to express orders from Winston Churchill that they should take the city and secure its safety. Instead, Sir Kinahan went back to his residence, had a candlelight dinner and played a game of bridge.”

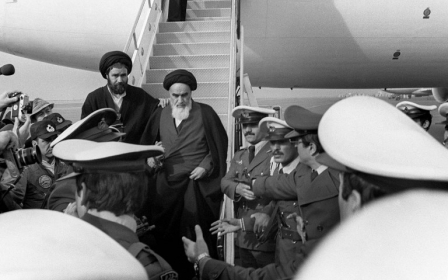

1953 coup in Iran

Could this be the reason that UK government censors want the file to remain secret after all these years? It would neither be the first, nor the last time that British planners used or created pretexts to justify their military interventions.

In 1953, the covert British and US campaign to overthrow the elected nationalist government of Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran included a “false flag” element. Agents working for the British posed as supporters of the communist Tudeh party, engaging in activities such as throwing rocks at mosques and priests, in order to portray the demonstrating mobs as communists. The aim was to provide a pretext for the coup and the Shah of Iran’s taking control in the name of anti-communism.

Three years later, in 1956, Britain also secretly connived to create a pretext for its military intervention in Egypt. After Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal and Britain sought to overthrow him, the British and French governments secretly agreed with Israel that the latter would first attack Egypt. Then, London and Paris would despatch military forces on the pretext of separating the warring parties, and seize the canal. The plan went ahead but failed, largely owing to US opposition.

Five years later, in 1961, it was a similar story in Kuwait. This little-known British intervention was publicly justified on the basis of an alleged threat from Iraq, but the declassified files that I have examined suggest that this “threat” was concocted by British planners. When Kuwait secured independence in June 1961, Britain was desperate to protect its oil interests and to solidify its commercial and military relations with the Kuwaiti regime. The files suggest that the British therefore needed to get the Kuwaitis to “ask” Britain for “protection”.

Kuwait intervention

On 25 June 1961, Iraqi ruler Abdul Karim Qasim publicly claimed Kuwait as part of Iraq. Five days later, Kuwait’s emir formally requested British military intervention, and on 1 July, British forces landed, eventually numbering around 7,000.

But the alleged Iraqi threat to Kuwait never materialised. David Lee, who commanded the British air force in the Middle East in 1961, later wrote that the British government “did not contemplate aggression by Iraq very seriously”.

Indeed, the evidence suggests that the emir was duped into “requesting” intervention by the British, and his information on a possible Iraq move on Kuwait came almost exclusively from British sources. The files show that the “threat” to Kuwait was being pushed by the British embassy in Baghdad but contradicted by Britain’s consulate in Basra, near the Kuwaiti border, which reported no unusual troop movements.

British intervention was intended to reassure Kuwait and other friendly Middle Eastern regimes that were key to maintaining the British position in the world’s most important region. The prime minister’s foreign policy adviser said that letting go of Kuwait would have meant that “the other oil sheikhdoms (which are getting richer) will not rely on us any longer”.

By the time we reached the invasion of Iraq in 2003, creating false pretexts for interventions had become a familiar theme in British foreign policy.

A matter of routine

To return to the 1941 document, British authorities have had a policy of either censoring, “losing” or destroying historical files that could undermine relations with current governments.

The files covered policies such as the abuse and torture of insurgents in Kenya in the 1950s... and the army’s secret torture centre in Aden in the 1960s

In 2012, an official review concluded that “thousands of documents detailing some of the most shameful acts and crimes committed during the final years of the British empire were systematically destroyed to prevent them falling into the hands of post-independence governments”, according to a report in The Guardian.

The files covered policies such as the abuse and torture of insurgents in Kenya in the 1950s, the alleged massacre of 24 unarmed villagers in Malaya in 1948, and the army’s secret torture centre in Aden in the 1960s.

Other papers have been hidden for decades in secret foreign office archives, beyond the reach of historians and members of the public, and in breach of legal obligations for them to be transferred into the public domain.

Whatever is in the 1941 document, if the British government is withholding its release for fear of upsetting relations with key allies, this would be less than surprising and more a matter of routine.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.