The Iraqi judges fighting to reform the system from within

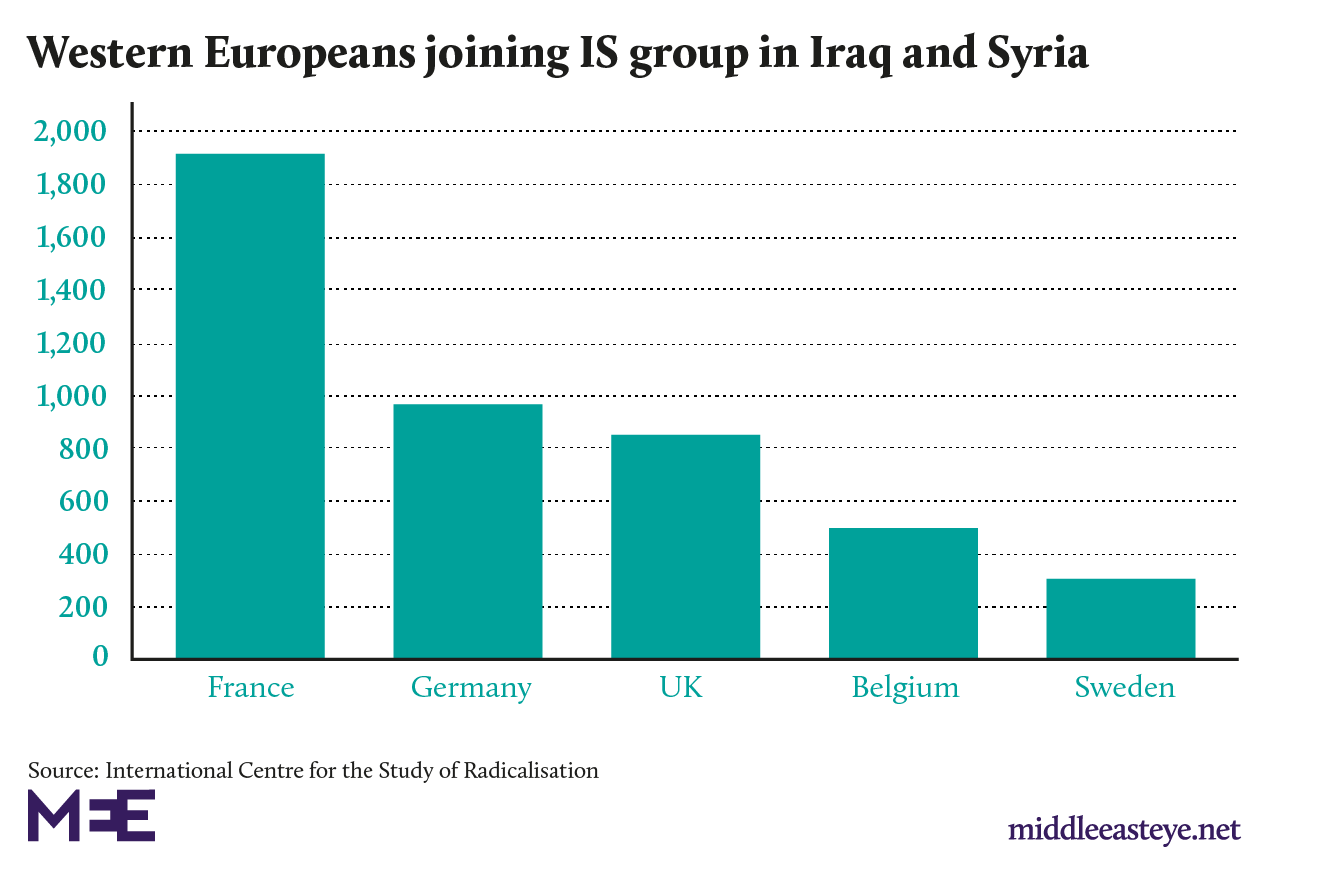

Last month's decision by a Baghdad court to sentence to death two more French nationals for belonging to the Islamic State group (IS), leaving all 11 Frenchmen transferred from Syria facing the gallows, has brought international attention to Iraq's judicial system.

Iraq has also tried thousands of its own nationals arrested on home soil for joining IS, including women, and begun trial proceedings for nearly 900 Iraqis repatriated from Syria.

The country remains in the top five "executioner" nations in the world, according to an Amnesty International report in April.

The number of death sentences issued by Iraqi courts more than quadrupled between 2017 and 2018, to at least 271.

But only 52 were actually carried out in 2018, according to Amnesty, compared with 125 the year before.

Judges in Mosul and Baghdad have repeatedly come under attack over their rulings, from so-called 10-minute trials to long prison sentences for the wives of IS members.

While it is undeniable that many flaws persist in a mostly corrupt and excessively bureaucratic system, improvements and attempts to reform the process also need to be acknowledged.

Several judges have spoken out against the country's counter-terrorism laws, especially the use of the death penalty, and some have travelled to the International Criminal Court in The Hague to gain valuable knowledge.

The Babylonian code of law

On a small shelf beside his desk, Salem Nuri, chief judge of the Appeal Court in Mosul and one of the judges trying to make a change, keeps a small sculpture of the Code of Hammurabi, the Babylonian code of law of Ancient Mesopotamia.

"This is the history of Iraq," he told Middle East Eye, taking it from the shelf and placing it on the stack of papers on his desk.

"The first codes of law in the world were born in this land. We believe in justice and the rule of law, and this is why judges in Mosul were the first target of the Islamic State in 2014 and before.

"We are now trying to work to restore our society."

Nuri left the city in 2014, together with his family, and moved to Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan Regional Government.

The Iraqi army retook Mosul in 2017, after a nearly nine-month-long offensive against IS.

Nuri's house was bombed and destroyed, along with it "all its memories," during the battle for Mosul.

Today, he can work again in his city, but every afternoon after finishing work he travels to Erbil

This is something Chief Investigative Judge Raed al-Maslah, another reforming judge, cannot do.

Maslah's family is in Baghdad, and every night he sleeps in a small room next to the office of the Special Court for Terrorism Cases in Tal Kayf, Nineveh's counter-terrorism court, 12km north of Mosul.

"I have to read all the files of the cases," he said, pointing to piles of papers.

"I have to see the newly arrested, to check the procedures. I go to visit some prisoners. But also for some security reasons, I don't move too much. Only every 40 days I travel to visit my family for a weekend."

'Ten-minute trials'

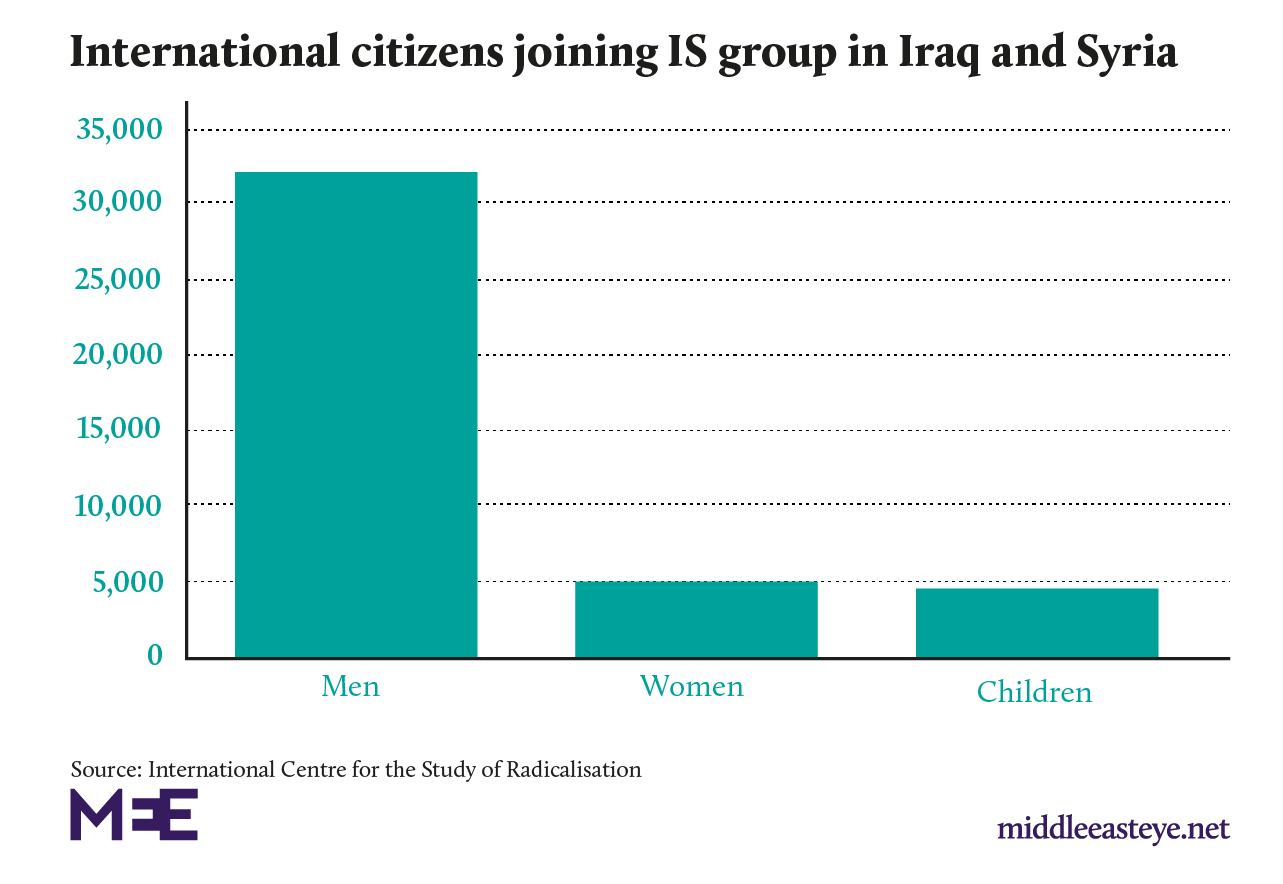

Following the battle for Mosul and the "defeat" of IS, Iraq's criminal justice system had to carry a heavy burden, having to investigate and prosecute the large numbers of IS detainees.

It quickly became the target of criticism from international human rights organisations for flaws in the trial of suspected IS members.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) documented and denounced harsh sentences given to several hundred people, including death sentences handed out under the number 13 counter-terrorism law of 2005.

So-called 10-minute trials by the Central Criminal Court in Rusafa, Baghdad - where critics said defendants were briskly dealt with without due procedure - especially drew the ire of the international media last year.

What went largely unnoticed were the investigations behind these hearings.

Recently, an HRW report recorded improvements in the procedures, detailing the work done in Tal Kayf, mostly under the guidance of Maslah.

"Our investigation work is based on documentary evidence and not only on confessions: we have witnesses' accounts of victims and survivors, but also videos, social media and forensic materials, and all the kinds of evidence supporting the investigation," Maslah told MEE.

"The media sometimes ruins our investigative work. On the contrary, we need international support because terrorism is a danger for all the countries in the world."

David Marshall, a former team leader of the accountability and administration of justice section of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI), told MEE last November that merely criticising the Iraqi justice system was "a little bit unfair".

Marshall has assisted many court sessions in Kharkh, Baghdad, where the process was significantly more professional than in Rusafa, he noted.

"Investigation files are thick. The 10-minute trials are the final hearings which summarised months of fact-finding and investigation that consists of numerous sessions," he told MEE.

Support from The Hague

Last July, Maslah took part in a pilot training scheme for Iraq at the International Criminal Court in The Hague, the Netherlands, supported by United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (Terrorism Prevention Branch).

The topic of the workshop was: "The Accountability of ISIL/Daesh in Iraq: Collection of Evidence, Trials and International Cooperation."

Maslah contributed together with the president of the Higher Judicial Council, Chief Judge Faeq Zeidan, to explain the challenges of the investigations, the collection of evidence, and the workings of the trials.

"We need an alliance to combat IS: we call on the countries in the world to share all the information, and if they don't want to judge the foreign fighters in their countries of origins, we will judge them here. This is necessary to do," Maslah said.

Gathering Iraqi judges in The Hague with practitioners from the international criminal tribunals allowed them to share their experiences as well as highlighting the international dimension of criminal trials taking place in The Hague.

In May last year, the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres appointed Karim Asad Khan as special adviser and head of an investigative team to support domestic Iraqi efforts to hold IS accountable for its actions.

The position arose out of a resolution passed in 2017 calling on the creation of such a team "to support domestic efforts to hold IS accountable by collecting, preserving and storing evidence in Iraq of acts that may amount to war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide committed by the terrorist group".

Khan, an international criminal and human rights lawyer, is currently working in collaboration with the Iraqi government and courts with a two-year mandate.

Counterterrorism law criticised

"But the problem is the [counter-terrorism] law of 2005," defence lawyer Firas al-Khazali told MEE, referring to law number 13.

"According to this law, every person accused of having a role – either a major or minor role - in a terrorist organisation is guilty and can be sentenced to a life sentence [20 years in Iraq] or death sentence.

'The media sometimes ruins our investigative work'

- Chief Investigative Judge Raed al-Maslah

"Iraqi judges and lawyers feel under pressure and are under threat because if they defend or forgive an accused, they might be considered IS supporters. We need first to reform the law."

Another judge in Baghdad, who asked not to be named, also told MEE about his discomfort with the Iraqi counter-terrorism law.

"I am against the death penalty, but sometimes according to the evidence collected during the investigations and so following the law, I have to sentence some accused to death.

"This doesn't belong to my being; it doesn't belong to my culture."

The same judge told MEE that in some cases he understood from the hearings that some women had nothing to do with IS and so he had ordered their release.

But then the cases were re-appealed, and he had to sentence them just for the affiliation to their husbands' organisation.

Same old faces

Iraqi judges and prosecutors are well experienced with terrorism-related cases to the point that they sometimes recognise some accused from previous trials.

"Many of the Camp Speicher massacre's criminals escaped from Abu Ghraib prison in 2013," Jawwad Hussein, previously an investigation judge, now appointed as criminal judge in Rusafa, told MEE.

"They found shelter in the desert in Anbar, and then they moved to all the provinces when IS took power.

"I know them personally, I already condemned some of them in 2010.

"Many others were in the local prison in the Salah al-Din province, I was dealing with their cases.

"They escaped on 10 June 2014 and in order to prove their loyalty to Daesh, they were ordered to participate in the mass killing of Speicher cadets two days later," he revealed, using the Arabic acronym for IS.

On 12 June 2014, IS killed around 1,700 Shia Iraqi air force cadets in an attack on Camp Speicher in Tikrit.

Mistaken identity

According to the law, the accused have the right to defend themselves, and a fair trial has to be guaranteed, but the accused often declare to have confessed their crimes under torture.

Defence lawyer Nour Khaled, who has dealt with terrorism cases for the past five years, told MEE: "I gained the trust of the families and so they call me.

"I take the cases when I am sure that the accused is innocent and he is unfairly in jail.

"I have to provide a medical report to prove that my client was tortured to confess crimes he never committed."

One of her clients, who talked to MEE after a court session and asked not to mention his name, was a former football player.

"I am accused of having put a hand grenade in an army car, but I am innocent," he said.

The lawyer said he is probably a victim of mistaken identity.

"We have many similar names in Iraq, and many innocent men are in jail for this reason," Firas al-Khazali said.

"Another problem is the secret informants. Some are working for the security services, some others are simply citizens who can accuse a neighbour for his or her own interests."

'Better to see a guilty man free than an innocent one in jail'

In investigations, all the information and declarations to find the truth have to be checked.

The judge should also open investigations on alleged cases of torture, but it rarely happens.

Khaled al-Mashadani, the chief judge of appeal in Kharkh, Baghdad, still has trust in the judges' work.

"I worked in Anbar from 2006 on, working on al-Qaeda crimes, I know their styles and methods, but it's very hard to judge all these cases," said Mashadani.

"In the difficulties or uncertainty, we will go on every day to condemn or set free a man, or a woman, in this country,” he told MEE.

"The principle we follow is written in a hadith [the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad], whose meaning is: 'It is better to see a guilty man free than an innocent one in jail,'" he said.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.