Arms, assets and war: Why Britain is betting on the Gulf after Brexit

One could follow the media’s coverage of the contest to become Britain’s next prime minister and learn almost nothing about Jeremy Hunt and Boris Johnson’s involvement in the war in Yemen. The omission is as striking as it is dismaying.

In their respective periods as foreign secretary, both men have played a key part in the creation of the world’s worst humanitarian disaster, while actively enabling the Saudi-led coalition’s indiscriminate killing of civilians.

As the Conservative leadership contest draws to a close, it is time to bring senior ministers’ guilt over Yemen to the foreground

As the Conservative leadership contest draws to a close, it is long past time to bring senior ministers’ guilt over Yemen to the foreground, and to examine the wider issue of the UK’s relations with the Gulf Arab monarchies as Britain contemplates a likely Johnson premiership and an uncertain post-Brexit future.

Bombing by a Saudi-led coalition is responsible for the majority of the tens of thousands of deaths in Yemen over the past four years since the start of the war. Experts reporting to the UN Security Council describe “widespread and systematic” targeting of civilians, while a blockade enforced by the coalition is the primary cause of a humanitarian catastrophe affecting millions of people.

Save the Children estimate that 85,000 infants have died from starvation or preventable disease since the war began.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A vital facilitator

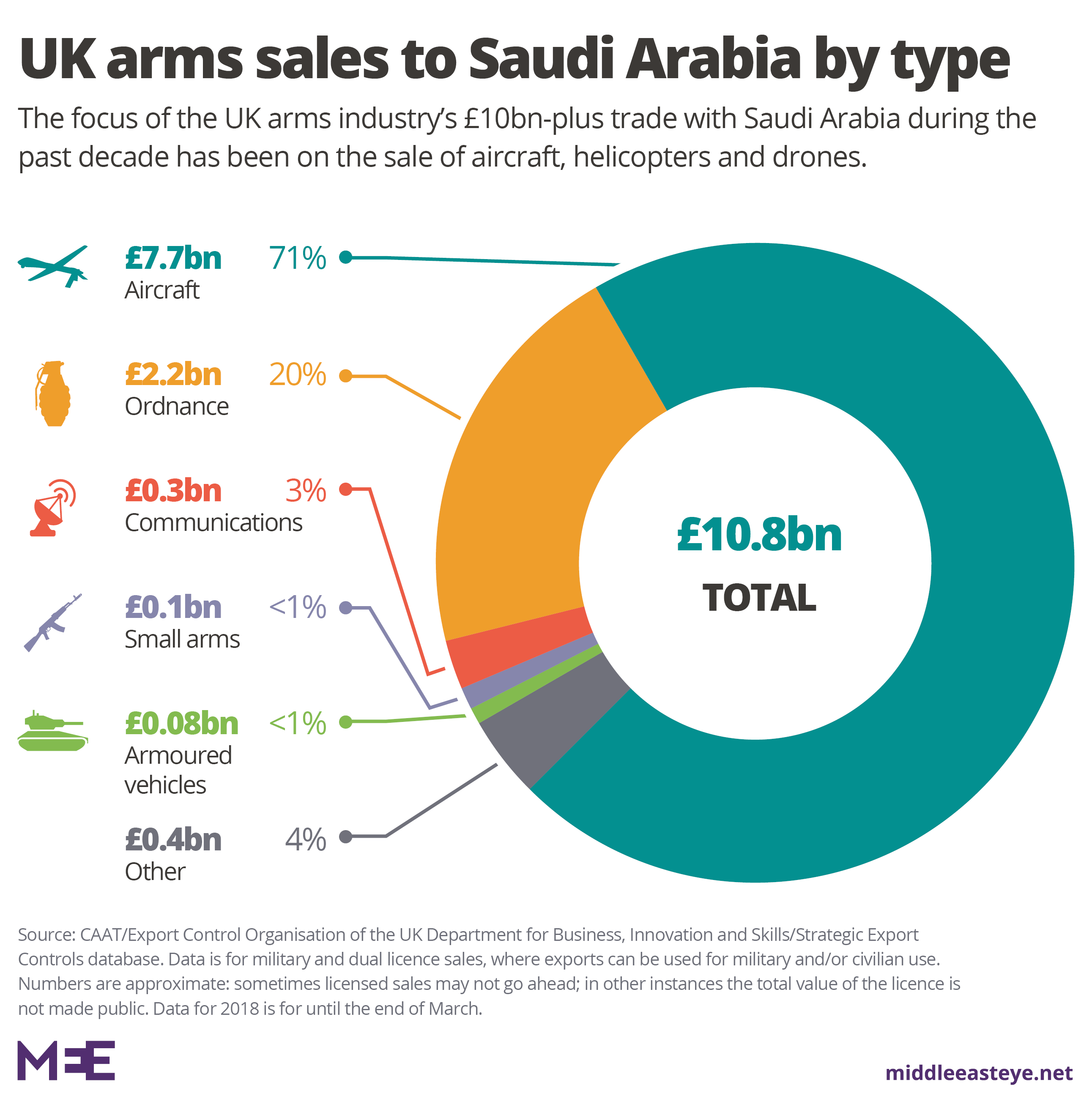

Senior ministers share responsibility for these deaths because Britain is a vital facilitator of the Saudi-led campaign. Around half the Royal Saudi Air Force comprises of British-built military jets which could not function without the technical and logistical support the UK provides.

This includes maintenance, spare parts and components, and, above all, replenishment of the bomb and missile stocks that have been pulverising the Middle East’s poorest country for the past four years.

But the significance of UK relations with Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf Arab monarchies goes well beyond the profitability of arms sales.

The then foreign secretary Philip Hammond pledged in 2015 to support the Saudis “in every practical way short of engaging in combat”. That support has been unrelenting ever since, under his successors, Johnson and Hunt, irrespective of the human cost.

Britain’s participation in the Yemen war is the product of a multifaceted relationship with those regimes that grew directly out of the days of empire.

Authoritarianism on the Arabian peninsula is not the product of the region’s culture, but of a set of socio-economic processes in which the British (and later the Americans) intervened to entrench and buttress monarchical rule over the better part of two centuries.

In the modern era, it is the Gulf’s "petrodollar" wealth that has shored up the ruling families and kept the Western powers committed to their survival.

A valuable trade surplus

Britain’s chronic and growing current account deficit is mirrored by the vast sovereign wealth accumulated by the current account surpluses of its Gulf allies. Net inward investment from the Gulf, particularly from Saudi Arabia, plays a major role in financing that deficit and stabilising an increasingly vulnerable pound.

British ‘free market’ capitalism has developed, to some degree, in symbiotic relationship with authoritarian Gulf rentierism

The City’s - and the wider economy’s - appetite for Gulf capital is matched by the Gulf elites’ desire to strengthen ties with their global north allies, particularly in the wake of the Arab uprisings.

The 2008 Qatari-Emirati rescue of Barclays Bank, alongside any number of high-profile investments, from Manchester City Football Club to the Shard skyscraper, should be seen in this wider context.

Meanwhile, the six Gulf monarchies collectively constitute the UK’s leading global south export market, with which it runs a rare and valuable trade surplus, thus reducing somewhat its burgeoning worldwide trade deficit.

Britain’s trade deficit and wider current account deficit are direct symptoms of the neoliberal economic turn taken by late prime minister Margaret Thatcher and consolidated and extended by her successors, wherein export industries declined markedly relative to the dramatic expansion of financial services.

In other words, British "free market" capitalism has developed, to some degree, in symbiotic relationship with authoritarian Gulf rentierism.

Petrodollar investment flows to the UK not only because Britain has the world-leading financial industry to absorb and process it, but also because Gulf elites know that Britain is one of a tiny few major powers that they can rely upon to ensure their survival.

An imperial decline

This factor is particularly pertinent when it comes to arms sales. Britain’s key strategic aim after World War Two – to remain a global power in spite of imperial decline - rests to a high degree on its rare ability to project military power on an intercontinental basis. This in turn requires a domestic arms industry, which is becoming increasingly reliant on major export orders.

Those orders have been drying up everywhere since the Cold War ended, except that is, for the Gulf, which now accounts for around half Britain’s arms sales. Those exports therefore help Britain cling on to its status as a second-tier global power, one capable of continuing to project power into the Gulf region in defence of its monarchical allies.

The violence of the Arabian monarchies is effectively British violence as well. Major exports such as the Typhoon jets now devastating Yemen form part of a wider relationship of military cooperation encompassing the arming and training of human rights abusing security forces.

Britain’s de facto support for the crushing of a peaceful and broad-based pro-democracy movement in Bahrain in 2011 was a chilling example of the strength of its commitment to the conservative regional order.

An ignoble role

Pro-Brexit ministers have placed much emphasis on the Gulf monarchies as part of their hoped-for reorientation of Britain’s foreign economic relations away from the European Union. But the bet is not a promising one.

The long boom in oil prices that began at the turn of the millennium has faded significantly in recent years, and if the world gets serious about dealing with climate change then a collapse in demand for fossil fuels could choke off the supply of petrodollars altogether, eliminating the entire basis of UK-Gulf relations.

Growing public revulsion over the Yemen war and the murder of Jamal Khashoggi may render those ties politically unsustainable in any event. Britain’s historic, ignoble role in the Gulf region may continue for a while longer, but at this moment nothing is guaranteed.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.