What will Bolton's dismissal mean for US policy in the Middle East?

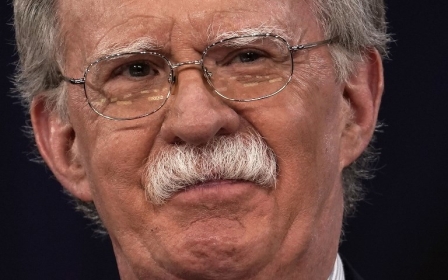

US President Donald Trump has finally fired his national security adviser, John Bolton.

The decision has been widely lauded in the US and internationally, but it should not be forgotten that it was Trump himself who initially hired him, sowing further uncertainty and fears about US foreign policy, which has rarely reached such levels of inconsistency.

Suffice to say that until a few days ago, the US was close to concluding after 18 years of apparently inconclusive war, a peace agreement with the Taliban, a group guilty of having offered logistical support to Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda for the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

At the same time, the US has been intensifying its economic warfare against Iran for months - the same Iran that in 2001, helped the US to overthrow the Taliban government in Afghanistan, and that in 2014-17 played an important part alongside the anti-IS coalition in defeating the self-proclaimed Islamic State on Iraqi territory.

Personal obsession

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

All this because Trump, who has cultivated a sort of personal obsession with what was achieved by his predecessor, last year decided to throw away the Iran nuclear deal, laboriously negotiated and signed just three years earlier - introducing an additional, unnecessary tension into an already worrying and complex international scenario.

For two years, we have also been waiting for the mysterious “deal of the century” to settle the Middle East conflict, entrusted to Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, who boasts a strong expertise in … real estate?! … and whose main concern for Palestinians was to allow them to “pay their mortgage”. That’s not a joke - he actually declared it.

While there is never a limit to the worst, it may be difficult to find in Washington a more hawkish exponent than Bolton to serve as national security adviser

Something must have gone really wrong if the US, which created and protected for decades the international political order, has started to tear it down, while the last great communist power has rushed to defend it, as Chinese President Xi Jinping did at the 2017 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

What Washington has produced so far is an exercise in vertigo, not foreign policy. This behaviour, unfortunately resembles a teenager in a hormonal storm.

While there is never a limit to the worst, it may be difficult to find in Washington a more hawkish exponent than Bolton to serve as national security adviser - but it would be ungenerous to attribute only to him this bleak landscape. It would be foolhardy to expect that US foreign policy could undergo a healthy shift with his departure.

Deeper malaise

Bolton is merely a more extreme manifestation of a deeper malaise that has long plagued Washington’s policy, related to the way in which the US conceives itself and its role in the world.

The US considers itself to be an exceptional country. It is difficult to deny it this quality, considering what it has achieved in the course of its history, and how much it has helped mankind to progress.

France cultivates this belief in its own way; even China is growingly and assertively showing its own form of exceptionalism.

The US, however, is the only country that genuinely aspires to export its political and cultural model around the world, starting from the belief - embedded in its citizens’ DNA - that only when the whole world is like the US, mankind will be realised, prosperous and happy.

Other countries might prefer other models for reasons linked to their cultures, religious beliefs and traditions - but the US political establishment seems to be a victim of a grossly distorted representation of reality, leading it to believe that those countries are without legitimacy, and thus a threat to the leadership and security of the US.

This demonisation of the “other” is being manifested against Russia, China and Iran.

The dynamics in relations between the US and China in recent years can be seen as a case study. While China might have adopted unfair commercial practices over time, to explain its extraordinary rise only through this prism - as the current US administration tends to do - further distorts reality. China’s rise is yet another self-inflicted US wound.

Expensive wars

In the last three decades, Washington has launched endless, expensive wars in the Middle East, and seen its economic activity spasmodically decline amid speculative finance.

Both choices have damaged the US and the rest of the world, from the 2008 financial crisis to the waves of refugees pouring into Europe.

China, meanwhile, has invested and innovated massively, taking hundreds of millions of its citizens out of poverty. Today, the bill for these different strategies has arrived.

The show recently put on by the US State Department, which offered millions of dollars, coupled with explicit threats, to prevent the Iranian oil tanker Adrian Darya 1 from delivering its cargo to Syria, has been depressing and embarrassing.

Such behaviour belongs to the world of organised crime, and should not constitute the modus operandi of a great power such as the US.

Trump may be able to identify an exceptional personality and pre-eminent expert on global affairs as his next national security adviser, but that person will have little room to improve the image of the US and the consistency of its international action, without changes to other aspects of US culture and the elaboration of its foreign policy.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.