From Sudan to Mali, how climate wars are breaking out across the Sahel

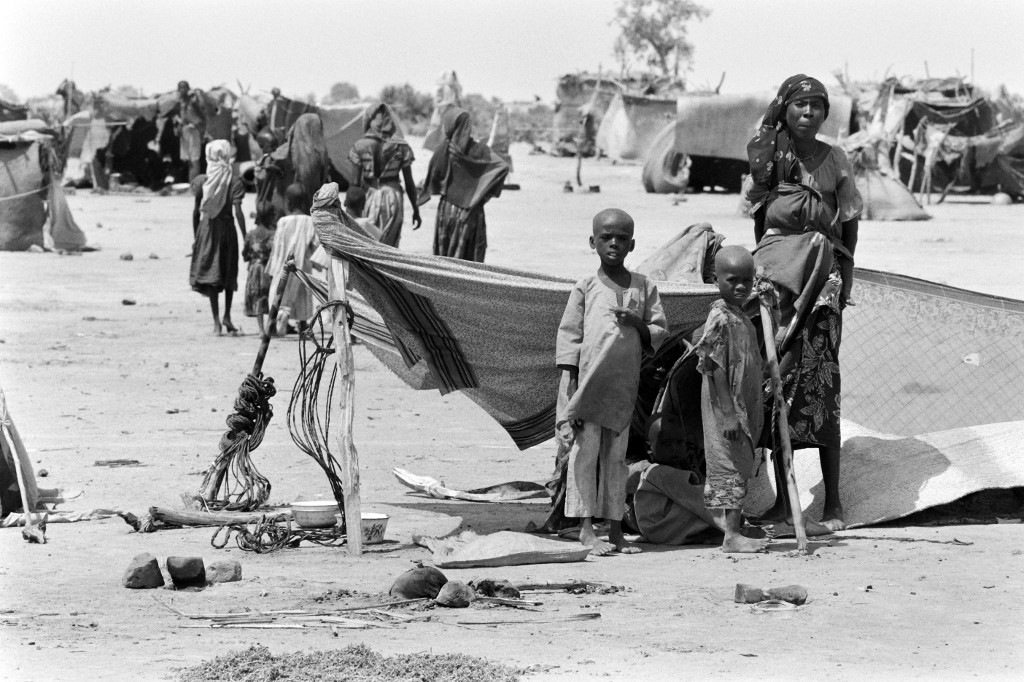

The bus to Khartoum delivered Maryam, and those of her neighbours who had survived with her, an escape from siege.

For months they had been hounded by horse-mounted gunmen roaming their village in central Darfur, forcing them inside and away from their farmlands until some of them could bear their imprisonment no longer and left their homes to confront their tormentors.

Maryam’s brother, Adam, was shot and his ear cut off. Her parents were killed.

“They burned our homes, they burned our farms. They killed my mother for riding a donkey. They said ‘you, you’re a slave, this donkey doesn’t belong to you.’ They shot her in the leg and they shot her in the heart,” Maryam told Middle East Eye.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

She has since spent seven years living precariously, selling tea on the streets of the Sudanese capital, and unable to return to her village after it was razed by the pro-government Janjaweed militias, who drew fighters from Darfur’s nomadic herder communities.

The ongoing violence that was inflamed in Darfur in the early 2000s killed at least 300,000, according to the UN, and led to allegations of genocide.

While the government’s Janjaweed enforcers were nominally deployed against rebels, the violence against civilian populations betrayed a wider conflict that is becoming increasingly urgent far beyond Sudan - one between transnational, nomadic pastoralist communities who seek space to graze, and land-bound farmers.

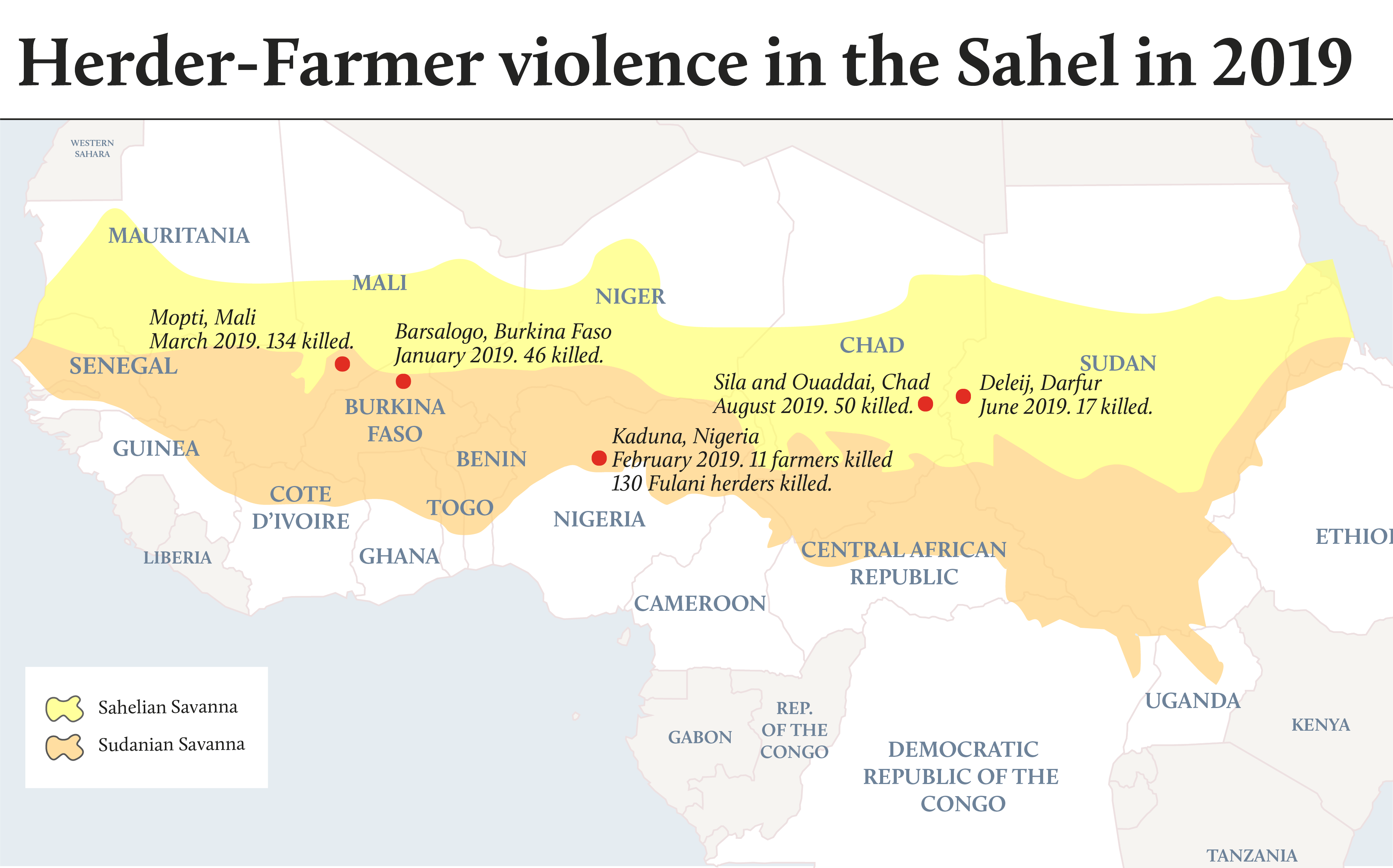

Since the height of Darfur’s violence, the whole Sahel region, which spans Africa just south of the Sahara desert, has become riven with such conflicts between herders and farmers over shrinking access to land and natural resources.

It has often been portrayed as a security, or sectarian, issue where groups like Al-Qaeda and Boko Haram have preyed on pastoralist grievances, but experts and the communities themselves say the conflict has been driven by climate change and exacerbated by government failures.

At least 37 people have been killed in 25 incidents in Darfur in 2019, according to local media reports which also highlight abductions and rapes by raiding gunmen.

An estimated 50 people were killed in neighbouring Chad in August, leading to a state of emergency declared in two states and the closure of the border with Sudan.

In March, at least 130 Fulani herders were killed in Mali, while other Fulani herders have routinely been blamed for violence in Nigeria.

“It is becoming a very serious issue in the whole Sudano-Sahelian region. I think it has very serious regional implications. It also has a very serious international implication in terms of security,” Abdal Monium Osman, senior emergency and rehabilitation officer at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), told MEE.

The root of the conflict was over access to natural resources which, for a variety of reasons, he said, brought communities into competition not only with each other but also among themselves.

“Livelihoods are basically dependent on natural resources and the issue is of access control. Any disturbance in terms of access has these kinds of implications.”

The greatest example of that kind of disturbance was a critical drought in the early 1980s that killed more than 1 million people in eastern Africa and saw Darfur’s communities come into conflict in ways that were described as a civil war.

This was two decades before the Darfuri rebel groups were fighting the Janjaweed, though some of the communities involved were the same.

They burned our homes, they burned our farms. They killed my mother for riding a donkey

- Maryam, Darfuri tea seller

“There are lots of communities who really haven’t recovered from that drought,” Alex Orenstein, a freelance analyst who uses satellite imagery to map and track the environments herders work in, told MEE.

The drought of the early 1980s, he said, is “what everyone’s scared of happening again”.

“Rainfall in West Africa, the Sahel and into Darfur as well, is so fragile. If you get this period when it doesn’t rain, it is costly.”

Orenstein’s analysis of satellite imagery in the Sahel has led to him warning of a potential threat emerging between Senegal and Mauritania because of a weak rainy season that is likely to mean not enough grass growth for livestock grazing.

Some analysts have boiled the conflict down to a phenomenon known as desertification, which describes the encroachment of the desert into the ever-shrinking space used by pastoralists, forcing them into conflict with farmers as they compete for resources.

Orenstein said that in recent years, at least some parts of the Sahel have had serious problems with a lack of rainfall, though there are other factors exacerbating conflict.

“Every year there’s going to be one spot that isn’t going to do well. And some of the spots are going to be recurrent,” he said.

“Drought is definitely a factor. Drought’s going to get worse. [In] West Africa and the Sahel, there aren’t mechanisms in place that can protect people and protect herders and farmers from the impacts of drought.”

Beyond security

Many of these same conflicts, though rooted in long-brewing tensions and competition, have been reported relatively recently purely through a security lens.

The violence between Fulani herders and Mali’s Dogon community is often connected to an armed rebellion in the country’s north in 2012 that included groups accused of connections to Al-Qaeda. The conflict involving the Fulani in Nigeria is likewise regularly associated with Boko Haram.

Earlier in September, Darfuris living in displacement camps after being forced from their villages since the early 2000s protested against being denied access to their farming land, claiming herders harassed them and were often accompanied by uniformed men in vehicles with mounted machine guns - an allusion to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary that evolved from the Janjaweed.

Osman said that there is a real danger that these long-standing hostilities caused by competition over resources are becoming militarised, by both armed groups and governments, and crossing borders.

The arming of Darfuri herders in the 1980s was, in part, linked to a flow of weapons from Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi channelled into Darfur to support Chadian rebels based there.

In more recent times, the UN has claimed Libya’s instability after Gaddafi’s fall has allowed advanced weaponry to reach herders across the Sahel.

“Over time it evolves. It starts local, over access to natural resources, and then it interacts with other actors and becomes a kind serious threat to regional, national and international security,” Osman said, suggesting as an example that groups like the RSF were using their substantial wealth to recruit mercenaries from other herding communities.

He said that is also distracting policymakers, with foreign aid providers focusing on security issues they feel are most relevant to their own interests.

“What I see in terms of intervention in this region is much more from a security perspective rather than development,” Osman added.

“If you look at the US and Europeans, what they’re looking at right now is much more security [focused], related to the Islamic fundamentalism. Unless there’s a shift in terms of how to look at those issues, I don’t see a way out right now.”

Herders shouldering the blame

“If you go on Twitter and go down the rabbit hole,” Orenstein said. “In Nigeria, on Twitter, you see people talking about Fulani herders and talking about them as foreigners.”

The narratives about the conflict, partially thanks to the security-focused framing, often gives the impression that aggressive pastoralists are to blame for the conflict. The reality is more complex.

Though herders are blamed for violence, they are as much a victim of insecurity when violence prevents them from reaching their preferred locations for grazing, and they are given no support from the government to sustain their livestock, despite comprising 40 percent of the agricultural economy in the Sahel.

Government policy failures have also exacerbated the environmental damage and competition, as well as the marginalisation of communities far from the capitals of affected countries.

In other cases, the problem is less about a lack of resources and more about rights over land, with herders grazing on farmland as well as farmers cultivating on land traditionally used by pastoralists.

A 2018 study by Sudan’s University of Gedaref estimated the amount of communal land used for farming in an area eastern of Sudan increased seven-fold between 2000 and 2014.

“People are always blaming the pastoralists,” said Osman, who pointed out that there can also be internal conflict within these communities.

“We also have to look at the historical neglect of the pastoralists and pastoral system and the marginalisation of the people who depend upon it.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.