Pipelines, pulp fiction and Maradona's 'Hand of God'

“I always say that if you look closely at your surroundings, you are bound to find something that will trigger the imagination," says Lebanese artist Rayyane Tabet, speaking at London’s Parasol Unit . "I am always after those moments, so whenever they happen, I note them down."

Much like a detective, Tabet takes incidents from his personal life and delves deeper into their context, uncovering a wider narrative that speaks of a collective experience. Steel Rings, main image, and the Three Logos of oil companies Caltex, Esso and Mobil, seen above, are part of his work on the Trans-Arabian pipeline.

(All photos by Benjamin Westoby, courtesy of Parasol Unit)

The Sea Hates a Coward consists of two great wooden oars suspended from the ceiling. The oars belonged to a boat that Tabet’s father rented in 1987 during the Lebanese civil war: his mission, which ultimately failed, was to row the family to Cyprus, away from the conflict. Now they stand suspended over the viewer, as if in remembrance of the journey of Tabet’s family - and the devastating impact of the civil war on millions of lives.

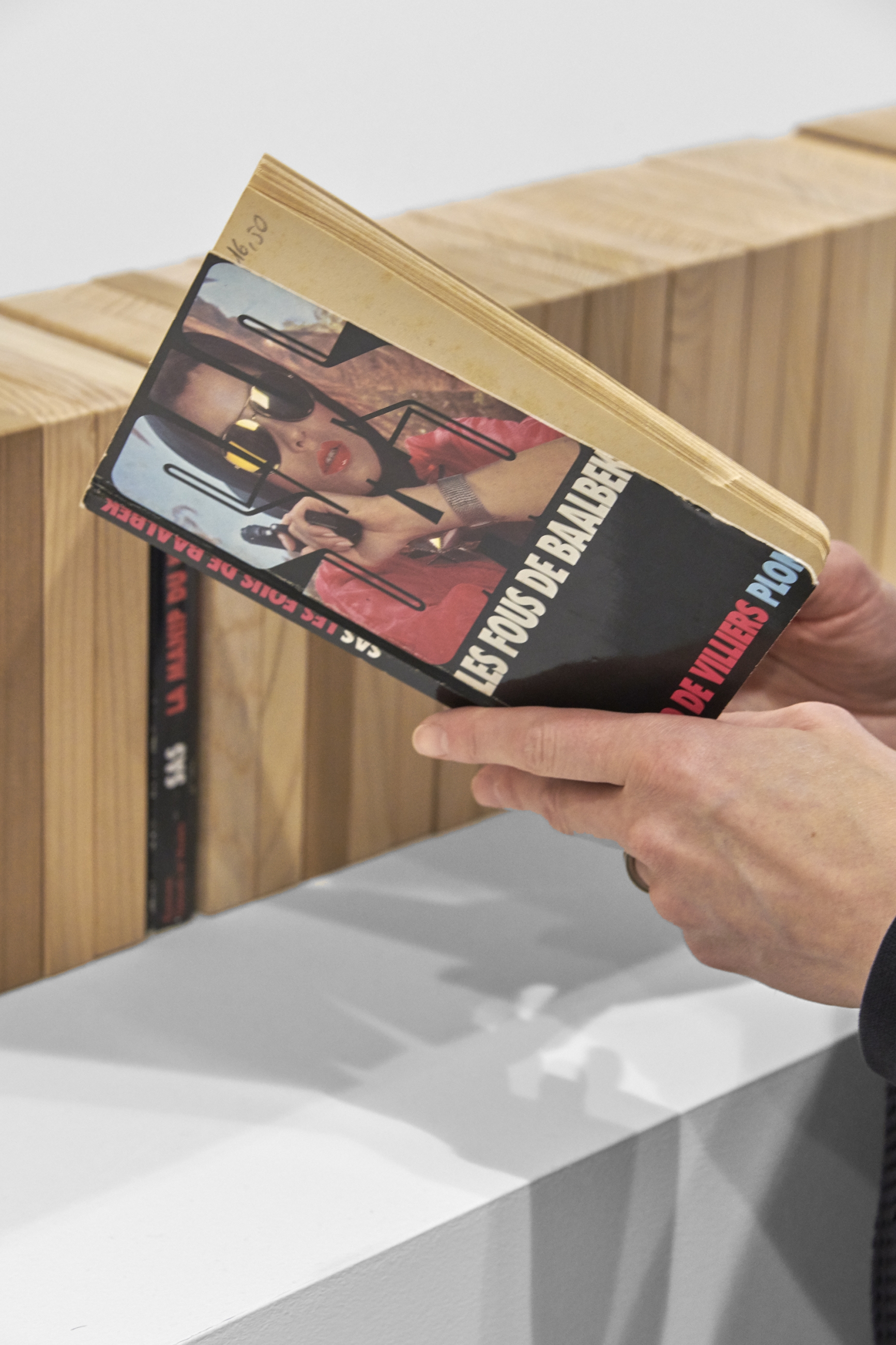

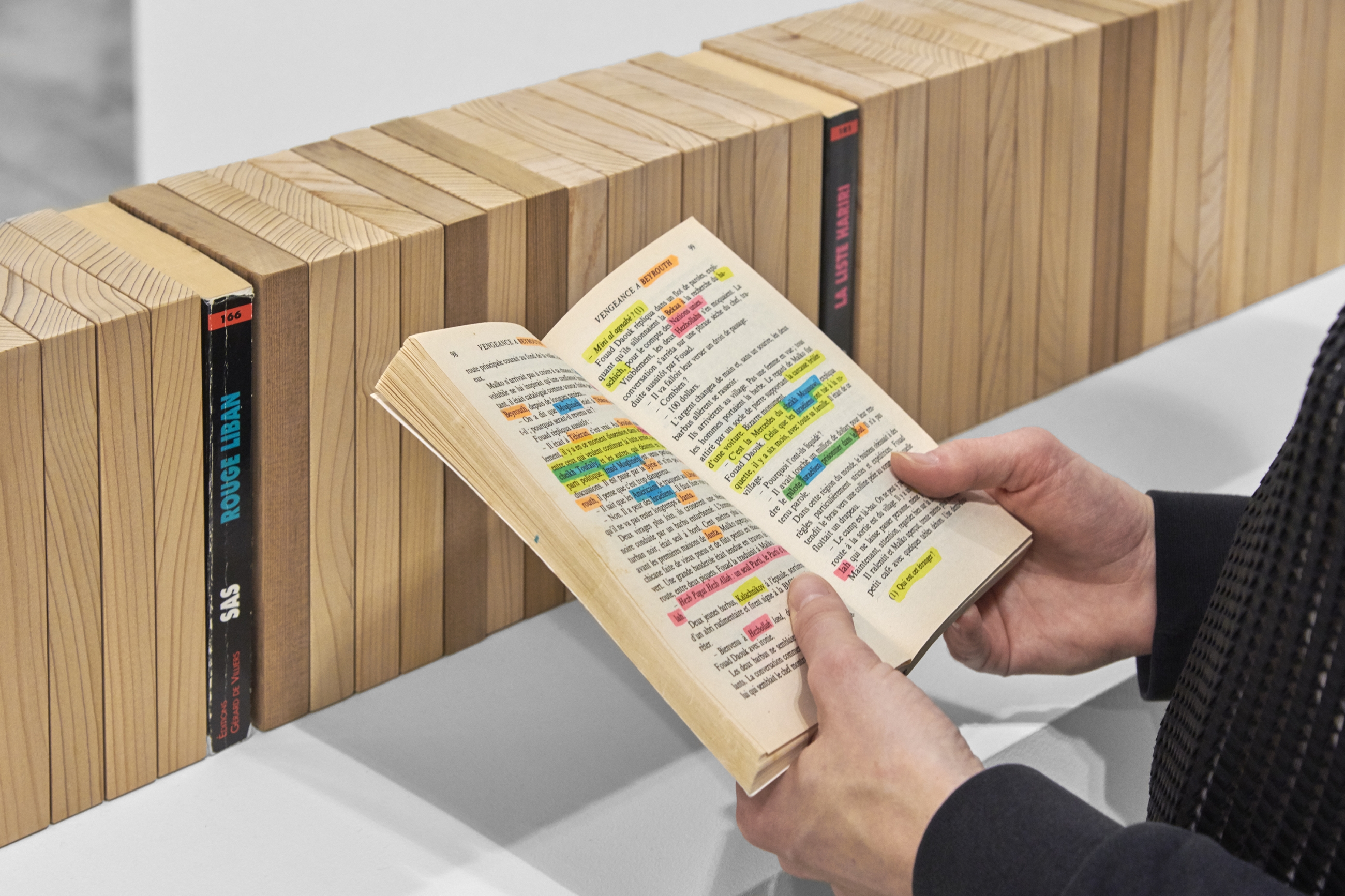

In the middle of the gallery floor lies a bookshelf containing a row of book-shaped wooden sculptures. Books have been inserted intermittently: they are taken from the SAS series by Gerard de Villiers, a French journalist-turned-writer, who wrote 200 pulp novels, six of which are set in Lebanon. On each cover, a woman poses suggestively with a gun. “You encounter these [books] in the Sunday market in Beirut, they are everywhere but you don’t take them seriously,” says Tabet.

Tabet discovered that not only did the novels span a crucial period in Lebanese history - from the start of the civil war to the tribunal for the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in 2005 - but also contained the real names of politicians, political parties and events from the conflict. “It not only follows a history of the country but it also does the thing that we [Lebanon] have not done yet," says Tabet, "it actually writes that history down, it is just that history is now hidden inside the pages of an erotic novel."

A Sanyo radio, which once belonged to Tabet’s parents, sits in the centre of the floor, playing the announcement of Diego Maradona’s infamous goal during the 1986 Argentina vs England World Cup match. The disputed goal, known as the "Hand of God", is one of Tabet's earliest memories. At the height of the Lebanese civil war, he says, radio presenter Charif al-Akhawi would broadcast a siren declaring incoming bombs, followed by advice on where to take shelter. But on this occasion, after the siren, he announced Maradona’s goal, bringing a brief moment of relief to the family of Tabet and others.

“What’s interesting is that it is not really about Lebanon, it is about another war", Tabet says, referencing the Falklands conflict of 1982, "and another moment and this idea that sometimes sports events mimic political tensions."

Extending across the gallery floor and outside onto the terrace are 28 rolled sheet rings. On closer inspection, each is engraved with the longitude, latitude and elevation of the Trans-Arabian pipeline. Opened in 1947, the pipe is the only physical structure to cross the borders of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon: it shut during the 1980s due to conflict but it is still in place.

Tabet recreated the pipeline with the same height, width and material as the original. “There is a tension between something that is formally quite elegant but then references this history of division, of borders and of socio-political tension,” he explains.

Across the top floor of the gallery stands an array of marble, sandstone and concrete columns and cylinders, some of which stand upright, while others rest on their sides. Colosse Aux Pieds D’Argile (The Giant With Feet of Clay), are the remnants of a 19th-century Beirut house, demolished like many older properties in favour of a skyscraper. “Beirut is a very interesting city where you have these contradictory, historical moments that have all left their mark on the urban environment of the city,” says Tabet.

Tabet gathered the broken columns from a house that was demolished, then combined these with used concrete samples from the skyscraper's foundations, drawing parallels between the two. “If you look at the Roman layer or the Ottoman layer or French mandate or even the post-war layer, these are projects that, if you look at the plans, think that they are going to transform the entire city but they end up transforming only part of it. So, you always have different styles clashing.”

Encounters by Rayyane Tabet is at the Parasol Unit, Wharf Road, London N1 until 14 December.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.