Lebanon protests: The people want the downfall of the banks

There is no shortage of corruption in Lebanon. According to Transparency International, people in Lebanon are the most likely in the MENA region to describe their politicians and state institutions as highly corrupt.

From the smallest bureaucratic transaction to the largest government contract, billions of dollars are drained from people’s pockets through bribery and from the public purse through embezzlement.

But the focus on liberal forms of corruption, as defined by Transparency International and other international actors, has reduced the crisis to a problem of bad governance. The ready accusation of “endemic” or “rampant” corruption is proposed by global consultancy groups, parroted by Western political leaders, and put to government officials by Western mainstream media.

Such accusations are coupled with a rehearsed formula to solve the crisis: austerity, more transparency, an end to clientelism, and drastic fiscal reforms.

Repaying the lender

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Such a diagnosis sits well with elites in the Global North eager to exonerate themselves and lay all the blame on their Global South counterparts. It also drowns the debate in legal and financial jargon about the rule of law and fiscal mismanagement, with few results.

Lebanon’s law against unlawful enrichment was passed 20 years ago but undermined whistleblowers rather than perpetrators.

Meanwhile, other major and invisible sources of corruption, such as chronic debt, are either discussed in passing, or invoked to justify more of the same antidote: austerity measures that include cutting major social services, and subsidies that benefit the majority of the population.

In Lebanon, corruption induced by debt has reached gigantic proportions, with serious consequences for the state and society alike

Outwardly, these cuts are about ending corruption. In effect, they redirect government expenditures to service public debt - that is, pay the rich lenders - and make way for profitable foreign investment.

In Lebanon, corruption induced by debt has reached gigantic proportions, with serious consequences for the state and society alike. Debt is the primary source of lawful enrichment. Lebanon has become the world’s third most indebted nation, with public debt estimated at $80bn in 2018 - a whopping 151 percent of GDP.

Understanding the structure of this debt, including the ratio of internal to external debt, is key to comprehending the current socioeconomic crisis that has spilled into the streets. It also helps to assign blame where blame is due, and to find remedies that would hold those responsible accountable, while minimising the price paid by their victims - the people.

Confiscating wealth

Public debt as a means of corrupting government administrations, avoiding taxation of the rich, draining the public purse, and confiscating the wealth of other nations is a centuries-old practice. Colonising by lending was common in the 19th century, when imperialist powers such as Britain invaded countries such as Egypt after the latter failed to pay their debts.

In the 20th century, international financial institutions took the lead role in imposing austerity conditions on Global South countries in return for securing loans.

These conditions followed a basic logic: cut down on government spending in order to keep servicing the debt, and create a favourable and stable financial environment for foreign investments. Exorbitant debt payments would lead to reduced public investment, social turmoil, de-development, and increased vulnerability to foreign interference.

As Michael Fakhri rightly points out, international lenders bear responsibility for the snowballing crisis in Lebanon, and Lebanon needs to free itself from the grip of imposed austerity.

But this is only half the picture: the history of Lebanese debt is atypical among Global South nations. More than half of Lebanon’s total debt is internal - held by local private banks - and is held both in Lebanese pounds and a foreign currency, the dollar.

In the post-civil-war era, then Prime Minister Rafic Hariri relied mostly on local debt to finance unproductive real estate booms and infrastructure. Sovereign debt grew at its fastest pace between 1993 and 1998.

At the turn of the century, the government turned to international markets and started borrowing in dollars (Eurobonds) under the political patronage of Paris. This created the second, dangerous feature of Lebanon’s public debt: a good chunk of it is denominated in a foreign currency. Should the local currency devalue, the cost of the dollar portion will skyrocket.

Pocketing the difference

Internal debt meant that local banks have reportedly raked in tens of billions of dollars in profits, thanks to generous interest rates offered by the central bank on recycling government debt. They were also subsidised by the central bank to facilitate personal, including housing and consumer, loans.

Private banks borrowed from the central bank for cheap and loaned money to ordinary people at a higher rate, pocketing the difference with few productive investments to show.

More than 700,000 Lebanese people have borrowed more than $20bn, more than half of which constitutes housing loans for close to 130,000 families unable to find affordable rents. This has created a debtor middle class nation, on top of an indebted state.

As long as the central bank was able to attract dollars to finance these schemes, the wheel of debt was turning. Traditionally, these sources were tourism, remittances, and shady capital seeking high interest rates and protected by banking secrecy laws. All three sources dried up in the past few years.

US financial sanctions sought to drain funds for armed resistance against Israel, the economic squeeze in the Gulf and West Africa reduced remittances, and private encroachment on public beaches and other attractions drove potential tourists to neighbouring countries.

With no productive export sector to generate foreign currency, the power-sharing elite turned to their last lifeline: international lending.

The CEDRE conference in Paris in April 2018 marked the latest attempt to refinance Lebanon’s debt and shift its composition more towards external rather than internal debt. Countries and international donors pledged an estimated $10bn in loans in return for the same old austerity fix: reduce government spending.

The WhatApp tax was one of many measures to find alternative sources of money, other than debt reduction. That’s when all hell broke loose.

Even after the eruption of mass protests, the now-resigned government tried to pass CEDRE recommendations under the pretext of reform, in hopes of getting the much-needed cash. Proposals for increasing taxes on bank profits were also included, but it was too little, too late.

The collapse of confidence in the state’s ability to pay its debts translated into a currency crisis. The hybrid composition of the debt makes for tough choices: slashing the internal debt means less foreign interference and requires a simple government decision, but is of higher risk to the thousands of Lebanese whose deposits were recklessly used to finance government debt.

Slashing external debt is harder to implement without international approval, but is likely to reduce the costs for the Lebanese population.

Risk of collapse

Both options, or a mix of both, are likely to lead to a devaluation of the Lebanese lira, which has been pegged to the dollar for a quarter century. An abrupt devaluation would impact the majority of people who earn and save in Lebanese pounds.

To avoid a national collapse, the banks have already started implementing informal capital controls by either shutting down or discouraging withdrawals on a case-by-case basis. It is not clear whether such restrictions apply to large depositors and the powerful political class.

The alliance between the banking lobby and the central bank has yet to be broken, and its liberal ideological foundations toppled

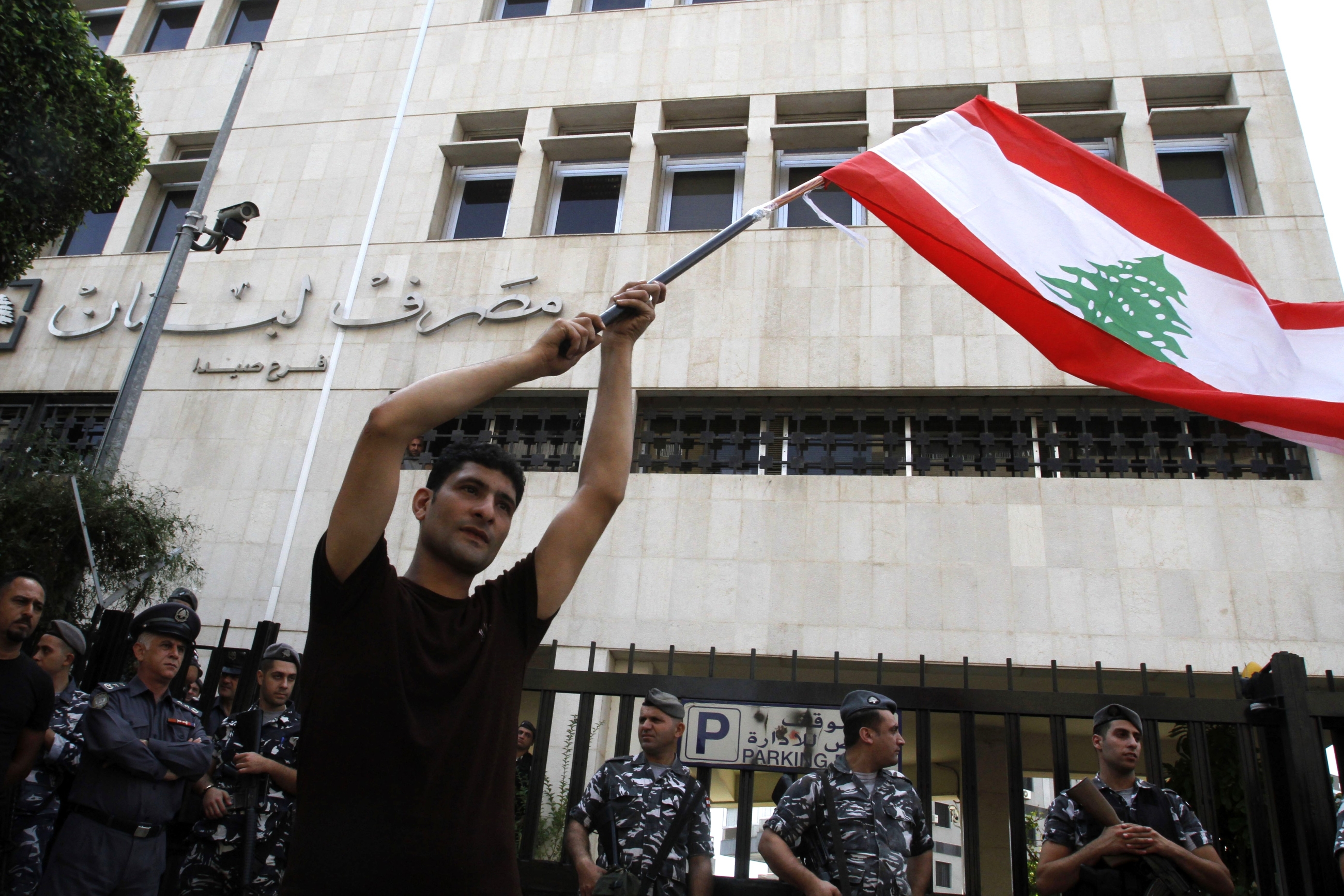

Thanks to the economic crisis, the longtime adulation of central bank governor Riad Salame has come under attack, as protesters have chanted against his governance in public squares.

Private banks have also felt the heat: two weeks into the uprising, several young activists stormed the country’s Association of Banks in downtown Beirut. The association, they protested, was the party of the rich seeking to exploit the poor.

They locked themselves in and issued a list of demands, including the recuperation of exorbitant profits earned by private banks on public debt, the denomination of housing loans in Lebanese pounds rather than dollars without interest rate hikes, and the outlawing of the use of dollars in the domestic market.

Soon after, they were detained by security forces, but later released under pressure from fellow activists.

These actions are significant but far from reaching a tipping point. The alliance between the banking lobby and the central bank has yet to be broken, and its liberal ideological foundations toppled. In the logic of protest, the downfall of banker power may be necessary for the downfall of the regime.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.