Former Israeli soldiers read out public testimonies against the army

The Israeli organisation Breaking the Silence held a 10-hour session on Friday 6 June in which public readings of testimonies of former and current Israeli Defense Force soldiers were read out. They were listened to by an influx of curious and like minded Israelis in central Tel Aviv’s Habima Square.

The 10-hour marathon event was set to mark the 10-year anniversary of the organisation which was founded in 2004 during the Second Intifada by a group of ex-IDF soldiers. Breaking the Silence was formed to give soldiers a chance to speak out about their experiences working in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Since its foundation, the organisation has collected over 700 testimonies from soldiers serving in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem.

An estimates 350 to 400 readers are estimated to have taken part, stepping up to the microphone and voicing the testimonies of the soldiers as a way to bring more attention to aims of the charity and the 47-years of Israel's military involvement within the West Bank.

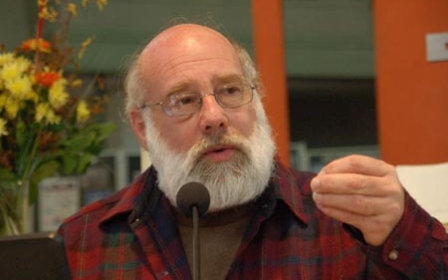

Below are a few of the former soldiers who participated in the event along with a section of their own testimony that they read out loud to the crowd.

Avner Guaryahs

You go into a house; just a family. You see the angry look in the child’s eyes. I think there is no doubt that you are just throwing more wood onto that fire. The child looks in your eyes. You humiliate his dad. You wake him up in the middle of the night. You enter his house again and again. His father says, ‘the army broke the door already and no one gives the money back for that’. The look in the child’s eyes; the anger. The parents quieting the child down, ‘quiet - quiet.’ You want the kid to yell at you, to scream at you. You want him to burst at you a little. Those are the small things that happened.

Itamar Shwartz

It was 2002 so there was the World Cup Final. In Israel this was around one or two o’clock. We were tired. The heat was killing us. What happened is that we stopped in one of the houses and they were talking in the radio ‘we need to find places with television. We need to see the Final’. This was the most absurd thing.

They went into a house with the women and the children. They put them into the kitchen and all of the soldiers watched the game. For two hours. I couldn’t even conceive what was happening.

Adi Mazor

I remember at first I was so proud of myself. Then from this feeling of being a hero, I felt so ashamed of myself. I felt like the Palestinian Territory was our playground, we could do whatever we want anytime we want.

Yoni Levy

Night after night it was the same; we held operations all over the city of Jenin in the West Bank. We use to initiate urbanite ambushes and detentions, but the most frequent operation was the aggressive entrances to city centers at the dead of night. During those aggressive entrances, we announced our arrival with a barrage of stun grenades and automatic weapon fire. Even though the grenades produced nothing but intense light and sound and we shot in the air or at streetlights, the effect was terrifying. Intentionally so.

Shay Davidovich

As for the village itself, tanks bombed and shelled the area around it while attack helicopters trained nearby. Of course, the soldiers entered the village and moved around within it. There were a lot of people, an entire battalion. There were also many fields beside the homes themselves, which the soldiers passed through freely. There were explosions. This was training for real, live. Live fire. I am sure it wasn't directed at the village, but you could really feel it all around. We walked mostly through Palestinian crops and entered the village through them. We proceeded through the streets in two rows. It was understood that this was simulating a real village, so the forces arrived in an organised fashion. I remember soldiers shooting blanks, I don't know how many.

Nadav Bigelman

It was hard for us to be with the settlers. We were in the center, the center of the kasbah, and the center of the settlement, and a lot of the troubles we had were with the settlers. Most of the violence didn’t come from the Palestinians, because they didn’t have a chance - there’s not much they can do with soldiers in front of them. Rather it was the settlers who were violent. I had a notebook in my pocket during my service, and each time the settlers cursed or acted violently, I’d write it down, and I also interviewed other soldiers and wrote that down.

Gil Hellel

On principle, they kept us on the ground as a mixed-gender unit in order to deal with disturbances caused by the Jewish folks. The population in the Jewish settlement, in Avraham Avinu, is known to be problematic. The entirety of Hebron is home to very extreme settlers that arrive there on a mission, so to speak, to conquer the Land of Israel anew. They would constantly harass the Palestinians who lived there, on a daily basis. I remember what I felt in the midst of this, that I asked myself "For God's sake, what am I doing here? Who exactly am I defending?"

Noam Chayut

There were big crowds trying to cross the check point going from Jerusalem to Ramallah, so going out of what we define as legal Israel. We would check them the same way on both sides. And there was this one Westerner, this European teenager or young woman. I looked at her and sort of waved to her that she could go around instead of waiting in the line. Then she moved a step back and started shouting at me in English ‘Why? What’s the difference between me and that woman with her babies crying in the line there?’ I could not answer her because I did not have didn’t have an answer.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.