From Basra to Minnesota: The Iraqi collector preserving traces of home

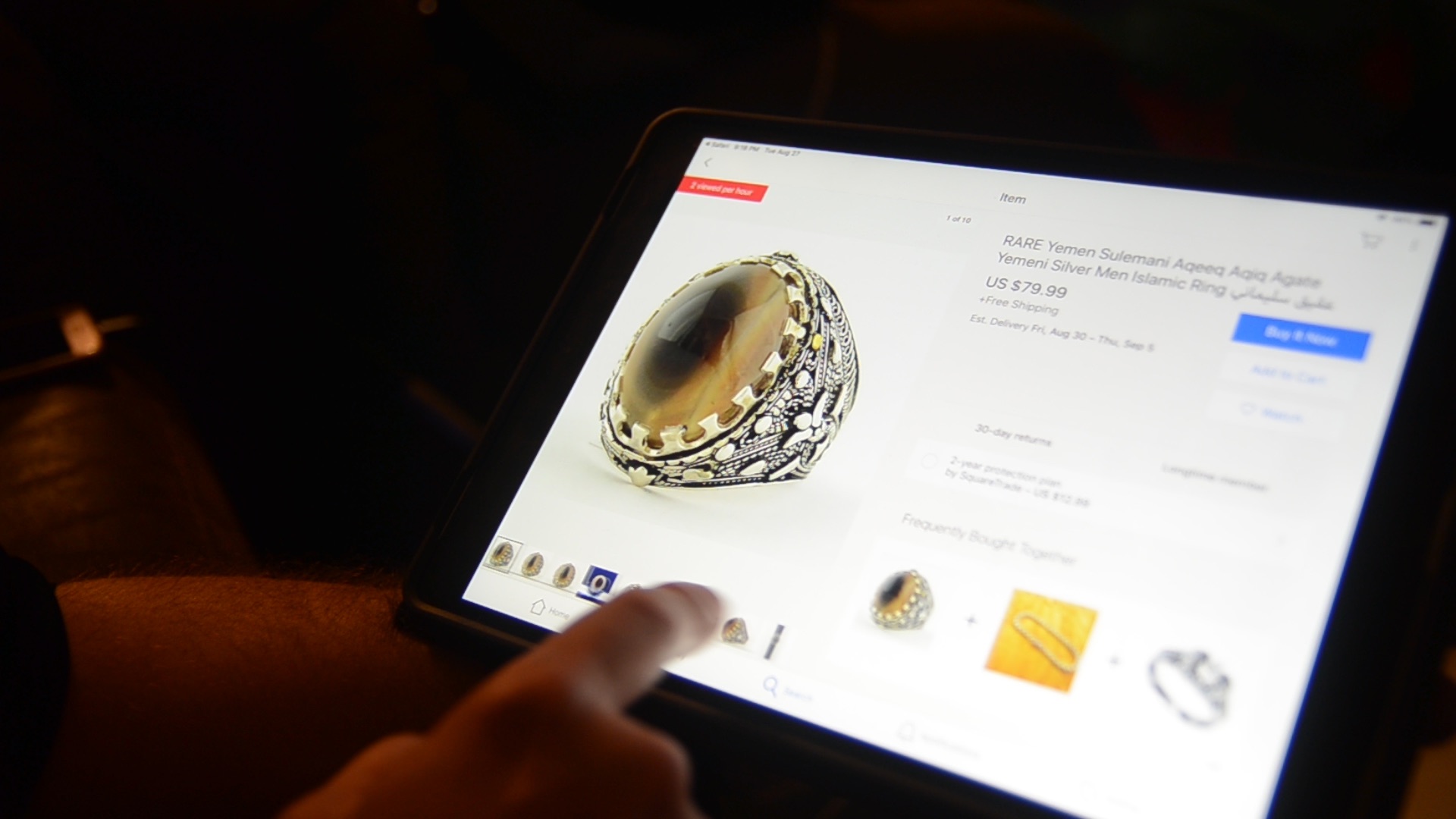

Ameer Al-Banoun picks up a heavy silver ring set with a Yemeni agate gemstone, turning it over in his palm as he eyes it with care. His apartment is crowded with objects he has handpicked and hoarded in every nook and cranny. Rings, gems and chunky jewellery, ornaments - some bordering on kitsch - spill over the surfaces of his shelves, sideboards and coffee table.

The silver ring is just one of hundreds of artefacts he has amassed since he moved to the US city of Minnesota more than 20 years ago, and which help him feel one step closer to home.

Originally from the Iraqi city of Basra, Al-Banoun now lives in a small apartment in Coon Rapids, a northern suburb of Minneapolis famous for its many parks and wildlife.

Items connected to his native Iraq are especially treasured: “I’ve collected a lot of items that have come off ships that docked at the Al-Faw port of Basra, my home city," Al-Banoun says. "Historically speaking, it has long been an obvious trade hub.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

One of these is a model of a ship made of oak, ropes and traditional sails, unlike the modern-day versions produced using sophisticated machinery. For decades, this style of vessel was used by fishermen in Basra.

'For me, it’s a labour of love. It’s like a full-time job'

- Ameer Al-Banoun

“I have three coloured ships dating back to 1929. All of them take me back to my city of Basra, where I grew up. These are part of our heritage, and it must be preserved,” Al-Banoun says.

Al-Banoun, 57, says he discovered this passion when he was just 14: “I used to see my father collecting prayer beads and old rings," he says.

Back in Basra, Al-Banoun worked as a labourer, taking any job that would tide him over. Now he doesn't work, but he spends his days labouring over collector’s items. He often stays up into the early hours of the morning browsing the internet for new pieces on sale.

From the practical to the purely ornamental, his collection is eclectic and seemingly indiscriminate - but it's the items that remind him of Iraq that hold him in thrall.

“For me, it’s a labour of love. It’s like a full-time job,” Al-Banoun says. "I keep them for the memories, they make me feel like I am still in my family's home, back in Basra.”

Fleeing Iraq

Al-Banoun's father was an accountant in Basra's provincial council before he was executed by the regime of Saddam Hussein in 1986. His murder, it is believed, was because Al-Banoun's uncle was involved with the opposition Dawa Party.

Al-Banoun fled Iraq in 1991, also fearing recrimination for his political beliefs. “I escaped Iraq because it had become known that I was an opponent to Saddam's regime,” Al-Banoun says. “I fled to Saudi Arabia, and stayed there for six years at the Rafha refugee camp, in the middle of [the] desert.”

Following a Shia uprising in southern Iraq, which was suppressed by Saddam Hussein in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf war, around 33,000 Iraqis ended up in refugee camps in neighbouring Saudi Arabia.

Secured by tall barbed wire fencing and heavily guarded by Saudi soldiers, the refugees near the town of Rafha, roughly 20 miles south of the Iraqi border, found themselves in relative isolation. “There was no life inside the camps, our fate was unknown,” Al-Banoun says.

Al-Banoun says conditions at the camp left him both mentally and physically scarred. He still suffers from the symptoms of spinal disc herniation that he says emerged during that period.

While Rafha camp had been described as "almost luxurious" with air-conditioned units and medical treatment, a number of its inmates including Al-Banoun reported maltreatment. He eventually left Rafha with the help of the UNHCR, which helped resettle thousands of Iraqis to at least a dozen different countries.

When Al-Banoun arrived in the US in 1997, he was awarded medical disability status and relocated to Minnesota, home to around 5,000 Iraqi migrants. The local council covers the rent on his apartment, and gives him around $700 in monthly expenses. It was then that he began to revisit his passion for collecting memorabilia, which had been inspired by his late father.

"The first items I bought were a set of prayer beads and valuable rings, like my father used to collect," says Al-Banoun. "But that was when I was a teenager in Iraq. The first item I collected in the US was a painting of Jesus, the prophet."

Keeping the memory alive

Al-Banoun often travels to other states, from Texas to Arizona, dropping in at garage sales and house clearances in his search for more pieces to collect.

As he drives to one of the "donation centres" or charity shops where used items are sold, he plays some of the Iraqi music he has saved on a flash drive in the car.

“When I listen to old Iraqi songs, I feel like I am driving down a road in Basra." he says. "I hope to one day come back when my country is safe and there is no corruption.”

But returning to Iraq is not yet an option for Al-Banoun, where since the beginning of October tens of thousands have joined ongoing protests that have left more than 500 people dead and tens of thousands wounded.

Demonstrators are calling for an end to corruption, unemployment and a lack of public services.

“I feel despair over what is happening back home. I often cry, seeing the videos of blood everywhere, and the human losses,” he says.

“I wish I could go back home, but when I think of who seems to rule Iraq now I don't dare to. To me, my life is worth more than a bullet. A bullet that does not even cost a dollar could end my life.”

Timeless treasures

Among Al-Banoun’s collections is a coffee pot called a dallah in Arabic. For centuries, this traditional pot has been used throughout the Arab world to brew and serve Arabic coffee, pronounced gahwa in Iraqi dialect. In traditional Arabian custom, a cup of coffee, or finjan, from the dallah is offered to welcome guests.

Another item that Banoun has collected is an oil lamp, or fanoos, similar to the ones he used during power cuts back in Iraq.

But his passion extends beyond Iraqi artefacts: "I like to collect. I probably take better care of the items I find than I take care of myself,” he says.

He also keeps reference titles including the 460-page volume The Book of Stones (North Atlantic Books, 2007), a book he regularly turns to in his studies of precious stones, many of which hold particular significance in Islamic history.

'The Iraqis born stateside must learn about their proud heritage'

- Ameer Al-Banoun

Another title he holds dear is Gemstones of the World, which includes notes on more than 1,800 gemstones, and The Crystal Bible, which details more than 200 crystals.

"It's important for me to know the true age of the items I collect," Al-Banoun says.

“You have a small museum in your apartment,” Al-Banoun says his friends tell him whenever they visit, as they marvel at the overflowing shelves.

It is comments like this, he says, that motivate him and bring him joy. But he insists that his real wish is for everything he has amassed over the past 20 years to live on, beyond the borders of home.

“If I pass away, someone will get my antiques," he says. "Collecting is a passion, and gives insights into one’s culture to a degree that is never taught at school. The Iraqis born Stateside must learn about their proud heritage.”

As to whether he will ever part with any of his prized posessions during his lifetime, Al-Banoun makes it clear that idea is one to let go: "I might sell myself but I will not sell the things I collect."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.