Tensions mount at Lebanon’s banks as customers push against capital controls

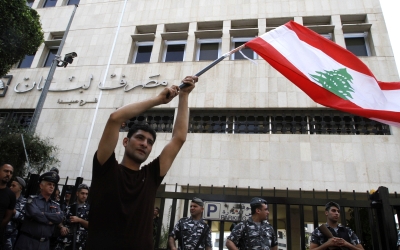

“Down with the rule of the banks,” read the signs that a group of protesters held, crowded under umbrellas outside the Association of Banks in Lebanon (ABL) on Wednesday morning.

Surrounded by a strong security presence, the demonstrators were there to express their opposition to informal capital controls on the accounts of small depositors.

Since September, Lebanese have been met with limits on withdrawals in both the local currency, the Lebanese lira, and in US dollars. The capital controls are said to be a move to retain liquidity in Lebanon’s ailing economy.

But for activist Dana Shdeed, the banking controls are “unfair” as they hit those with low and middle incomes the hardest.

Anger has mounted on both sides of bank counters at the beginning of the new year. Citizens are demanding tellers surrender up cash, while bank employees say they are acting on instructions from the ABL and are unable to deliver customers the money they ask for.

The union of bank employees threatened a strike on 2 January, asking for security agencies’ protection against what they called “organised attacks”.

Bank employee Georges says the conflict between customers and tellers is “confusing”. Preferring not to share his last name or which bank he works at, he told Middle East Eye: “You are torn between the people and your own security.”

Since the union’s statement, Georges says one or two police personnel have been stationed at most bank branches, while protest groups have urged citizens to keep things peaceful to prevent the banks from shutting their doors.

Yet as the Lebanese lira slips further away from the dollar on informal exchange markets - the official rate is 1,500 to the dollar but on the street, the lira's selling for over 2,000 - analysts say swift action is needed to mitigate the tense situation.

“The condition of the lira is collapsing,” Wednesday’s protestors chanted.

‘Chaos’ at bank branches

Incidents at branches of Lebanon’s banks have become thick, fast and unpredictable at the turn of the new decade.

In recent weeks, videos have been circulating on social media showing a man with an axe at a bank branch and arson attacks at branches in the Baabda and Keserwan districts.

One piece of footage showed a man launching himself from the top of a parked car to join a tussle between security personnel and citizens outside another bank.

Confrontations across bank counters are the result of struggling Lebanese' determination to access more of their deposited money than they are allowed.

Alongside the dollar peg's uncertainty, prices are rising. And with businesses struggling, some are not being paid their salaries on time.

The effects are being compounded as employees are unable to cash paycheques, with some complaining of being subject to restrictions on withdrawals as low as $100 per week.

Sara al-Khoury*, a contractor for the environment ministry, said that she had not received her salary for nine months, and has been limited to withdrawing $250 a week by her bank BLC.

Others have opened multiple new accounts to try to meet payments for their rental properties or for school fees.

Mokhtar Ghazzawi, who works in the oil and gas sector, told MEE that he felt things were getting worse. “People are getting frustrated and it is like a snowball,” he said. “Day in, day out, it is mayhem.”

The bank employees union (FEDSLEB) issued a statement last Thursday, calling for an end to the “chaos” at bank branches. The confrontations will not help depositors get what they want, said the union, and it is not down to bank employees whether or not to dispense cash.

Lebanon's many banks shuttered for several days when an ongoing protest movement erupted on 17 October, worried about security and a run on the banks. Bank employees warned they could close again if violence continues.

“Imagine if they close the banks, it would be much worse,” said Georges.

Following the stationing of police at most bank branches, the pitch of confrontations at branches seems to have calmed down. Yet queues continue to stretch outside branches before opening times.

Financial woes

Lebanon’s once-strong financial sector has become increasingly unable to meet debt-servicing payments, as ratings agencies have continued to downgrade the country’s credit score over the winter.

The stream of foreign currency coming in remittances or from Gulf investors has dried up; the gap between Lebanon’s foreign reserves and due payments has yawned, and the agencies say there is an increasing likelihood that Lebanon will default on its debts.

As the balance of payments worsens, the exchange rate looks increasingly brittle. The dollar is now trading for as much as 1.5 times its official value on parallel markets.

The ABL announced the weekly limit at $1,000 in November. Yet as the outlook for Lebanon’s economy has remained negative, the capital controls at Lebanon’s banks have crept down to a fraction of that sum.

Despite the limits on accounts, as confidence drains so has Lebanon’s dollar liquidity. According to reports, $3.8bn left the country in November.

Nisreen Salti, associate professor of economics at the American University of Beirut, says the dollar run has not been stemmed because there is no legislation backing the controls, so they are not being uniformly implemented.

So far, the controls have been “decentralised, unsystematic and discretionary”, and have therefore contributed to “the general panic” and the pressure from customers, she told MEE.

Local media reported on Tuesday that a ruling from a Court of Urgent Matters had obliged Byblos Bank to authorise the transfer of $1m out of a complainant’s account, as well as fining the bank.

Salti, along with a team of economists including a former minister, has contributed to an article which anticipates that some form of capital controls are likely to be necessary.

Yet the president of the Lawyers Syndicate, Melhem Khalaf, dismissed the current controls as “illegal and unconstitutional”.

If controls are necessary to stay in place, they must be backed up by legislation, Khalaf wrote in a statement last week.

Shdeed, the activist, also complained of the lack of legislation, which she said contributed to the pressure on smaller depositors, while those with more capital were still able to move their dollars out of the country.

Speaking to MEE, Salti agreed with the need for a legal framework.

“My sense is, if payments and costs imposed on citizens are part of a credible recovery effort, then they will meet less resistance,” she said.

What next?

As of yet, the future is uncertain. Although the ABL said in November that the directive was a “temporary” measure and was due to the “exceptional circumstances”, there is little indication of how long the current situation will last.

Two members of the ABL declined to comment to MEE for this article.

Even with more effective capital controls in place, Lebanon will likely require extreme changes to its fiscal and monetary policy.

“Capital controls alone are not a solution to our balance of payment problem,” said Salti.

“Even if they were applied transparently and systematically, they could, at best, marginally slow down the decline.”

The team of economic experts recommended a three-year programme to avert a “lost decade” for Lebanon.

They recommend that Lebanon will need a bailout of between $20-25bn to deal with its insolvency crisis and that a managed devaluation will likely be necessary at some point in the future.

*Name has been changed at the interviewee’s request.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.