The Idlib debacle is a reality check for Turkish-Russian relations

Within a week, Russia-backed Syrian regime forces killed a total of 13 Turkish soldiers in two deadly attacks in Syria’s northwestern Idlib province.

Needless to say these attacks wouldn’t have taken place without the approval of the regime’s main international backer, Moscow. And this is where Turkey’s predicament starts, if not deepens.

Russian-Turkish relations in their current form are products of political realism, pragmatism, and shared discontent with the West

These two attacks brought to the fore the contradictions, limits and nature of Turkey and Russia’s fast-improving relations in recent years. Despite the casual usage of the word "strategic" by some Turkish officials and pundits in depicting the nature of Moscow-Ankara relations, these bilateral ties are far from being qualified as such.

Russian-Turkish relations in their current form are products of political realism, pragmatism, and shared discontent with the West. There appears to be much more clarity on the Russian side when it comes to defining both the nature and quality of these relationships, which can be characterised as transactional and utilitarian, when compared to the case on the Turkish side.

Ankara often appears to have read too much into these relationships.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A reality gap

The Russian-led Astana and Sochi processes were not only about Syria, but also about reformulating the nature of the relationships between three powers, Russia, Turkey and Iran, but particularly between Moscow and Ankara, within the context of Syria.

In spite of these reformulations, the strategic contradictions and geopolitical divergences between Russia and Turkey on Syria and beyond have remained just as wide in the aftermath of the Astana process as prior to it.

Additionally, looking at the nature of Russian responsiveness, or lack thereof, recently in terms of Turkey’s concerns and requests over Idlib, it is clear that these relations are not premised on symmetry, as Turkish officials often emphasise.

Rather they are asymmetric, if not hierarchical, in favour of Moscow. And it appears that Russia’s partial accommodation of Turkey as part of the Astana process has also run its course. Now, with both sides engaged in a war of attrition, they are testing each other’s limits in Idlib.

Turkey certainly has its options in responding to Russia and the regime in Syria and beyond. However, none of these options are good. In spite of this ominous picture, it is highly likely that Turkish-Russian ties will survive this episode. These relations are still too useful for both sides to give up on.

Likewise, both parties are set for significant losses if their relations break apart over Idlib - which is still unlikely.

Yet, if this spiralling crisis isn’t contained, this episode will not only reveal a reality gap in Turkish-Russian relations, but it will also have a formative or qualitative impact on these same relationships. At this stage, the questions that beg answers are as follows: what are Turkey’s goals and what are Turkey’s options in Syria, vis a vis both Russia and the regime?

The real goals

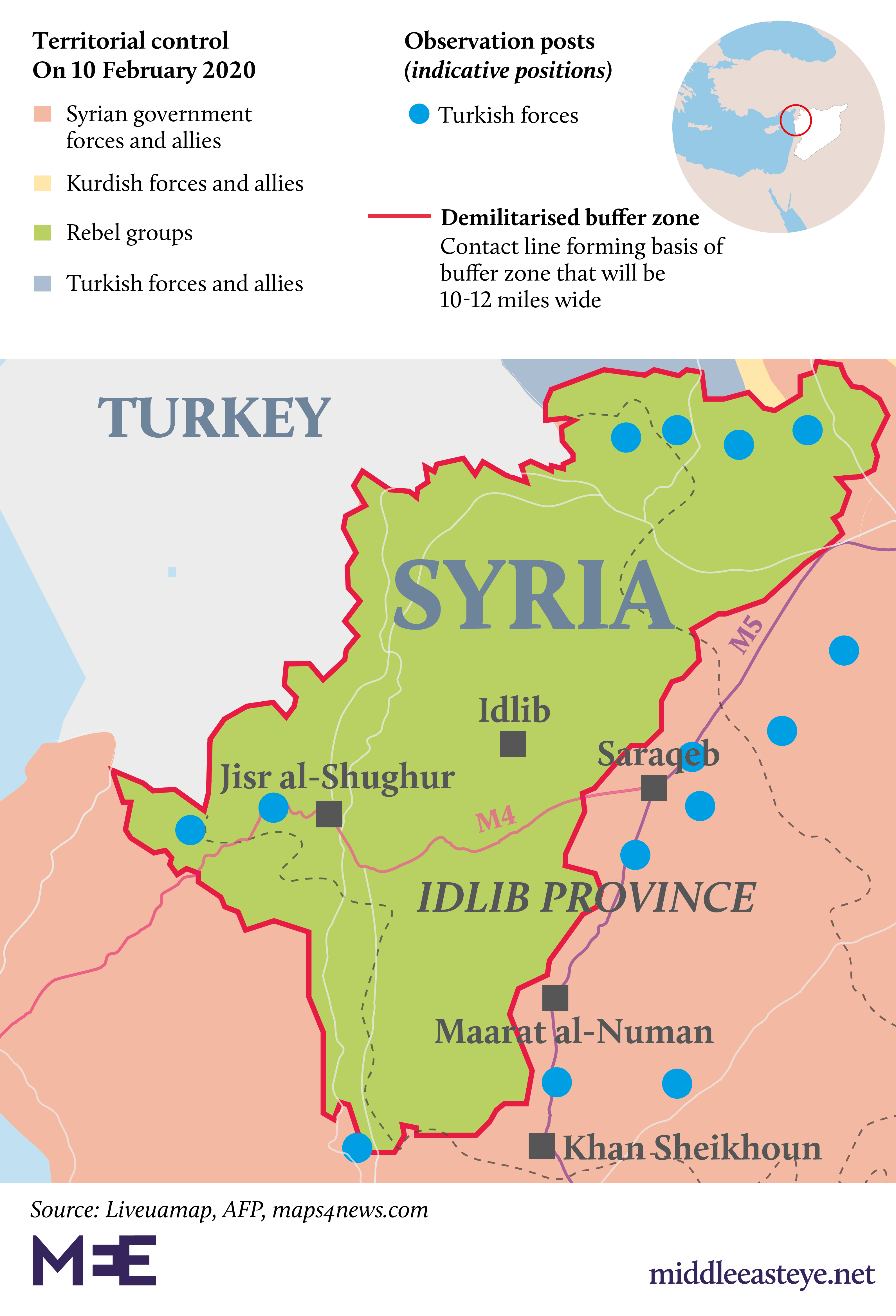

By maintaining a significant military presence in Idlib and elsewhere, Turkey aims to achieve the following political goals. First, Turkey’s most immediate aim is to stem the tide of refugees flows towards, if not across, its border. According to UN officials, since 1 December 2019, around 700,000 people have fled their homes towards the Turkish border.

If the regime continues with its military offensive, particularly bearing in mind that at some locations the regime is only 10km away from the city of Idlib, this number will soon reach millions.

The government is already threading a difficult line on refugee issues domestically (partially, it has itself to blame for its growing political difficulties on this issue) and is determined to keep the refugees on the Syrian side of the border.

However, keeping people on the Syrian side of the border is at best a crisis-management solution, but not a sustainable policy. Related to this, Turkey is also concerned about the presence of radical elements on its borders that can easily intermingle with the refugees.

Second, Turkey wants to link the future of its military presence in Syria, and Idlib at large, to the political process in Syria in order to extract concessions from the regime. In this respect, if the regime continues to advance in Idlib militarily, the value of Turkey’s leverage will be significantly reduced.

Third, in a similar fashion, Turkey wants to leverage its military weight in Syria during the political process in order to minimise political gains for the Syrian Kurds - in particular it will strive to prevent any prospects in which the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in particular could attain any political status or form of constitutional recognition. The SDF is mostly made up of YPG fighters which Turkey considers a "terror group".

Possible scenarios

To attain these goals, Turkey feels obliged to up the ante, particularly after its repeated talks with Russians have produced no results. To that end, Turkey has undertaken a massive military build-up in Idlib. Ankara has dispatched hundreds of soldiers and commandos, and military vehicles (including armoured vehicles, howitzers and tanks) to Idlib.

Turkey is also facilitating reinforcement of the Syrian opposition ranks. Militarily, however, since the airspace in northwestern Syria is controlled by Russia (and therefore not open to Turkey), Turkey’s military activity will face significant vulnerability.

Given this backdrop, what options does Turkey have?

First, if the regime and Russia push ahead with the current military advances, that means further escalation between Turkey and the Syrian regime and Russia. In this scenario, Turkey will likely pursue the policy of driving up costs for Moscow and Damascus, and widening the geographic space of this escalation.

Russia’s position to the east of the Euphrates is still vulnerable. Plus, the US presence in this area can be a boon for Turkey. Lastly, Aleppo will become a vulnerable target for Turkey and the opposition’s counter-offensive strategy. By increasing the cost of the escalation for Moscow and Damascus, Turkey would want to force Russia to cut a new deal.

Second, in a similar fashion, by pursuing a heavy military build-up in Idlib, as it is currently pursuing, Turkey wants to reestablish a balance of deterrence with the Syrian regime and Russia. Indeed Turkey is trying to send the message that it will not hand over an easy victory to Russia and the regime. On the contrary, Ankara is signalling that it will make Russia and the regime’s military solution for Idlib catastrophically costly for them.

The Idlib debacle

Third, building on the previous two options, Turkey still prioritises exploring further options with Russia in order to cut a new deal or create some form of a buffer zone, with new demarcation lines for the people fleeing the regime’s offensives.

Turkey doesn’t have any good options in Idlib

This is still the most likely scenario in Idlib.

If this scenario materialises, Turkey will then strive to get Europe involved financially in the creation of such a zone. However, one of the major challenges that will face any new deal on the formation of a buffer zone will be the matter of a no-fly zone arrangement as part of this deal.

But this in return will beg another question: to what extent any such buffer zone can be free of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a militant group which controlled most of Idlib, and thereby prevent the Russians from having a pretext to attack this area down the road.

The Idlib debacle is thus acting as a reality check for Turkish-Russian relations. Moreover, as the above options reveal, Turkey doesn’t have any good options in Idlib. All the above scenarios at best can be seen as crisis management responses, rather than sustainable solutions. This in return requires Ankara to reassess and reformulate its policy in Syria.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.