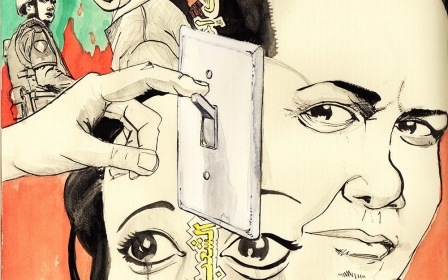

Mubarak: A cautionary tale for those who dare to dream of a better future

The outpouring of public and official sympathy over the death of ousted Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak on Tuesday was a classic example of Stockholm syndrome - the irrational behaviour through which hostages develop a psychological alliance and emotional bond with their captor during (and in this case, after) captivity.

It’s easy to blame the loss of a nation’s collective memory on the inevitable passage of time, when the real culprit is shameless propaganda, disinformation and sheer lies.

The plan to obliterate the truth about the disastrous impact of Mubarak’s 30-year dictatorship through intentional doses of whitewashing media was set in motion on that fateful day nine years ago, 11 February 2011, when a popular uprising forced him to step down.

Failed uprising

After Mubarak handed over the reins to Egypt’s de facto rulers, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), it soon became clear that the “new Egypt” was not so new after all.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The polarisation was instantaneous. During the “glorious” 18-day Tahrir sit-in, pockets of Mubarak supporters attempted to stage counter-protests at central squares throughout the capital. On 2 February 2011, thugs stormed Tahrir on horseback and camelback, attacking protesters in what came to be known as the Battle of the Camel. Though they “lost”, the symbolism of this violent confrontation foreshadowed and encapsulated the eventual failure of the uprising to bring about real change.

Sisi, who briefly attended the funeral, is a continuation of the Mubarak legacy - the evolved form of a ruthless and corrupt administration

Hence, it came as no surprise that Mubarak was given a full-honours military funeral complete with cannon fire, horse-drawn carriage and an official three days of mourning. After all, Egypt’s current president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who briefly attended the funeral, is a continuation of the Mubarak legacy - the evolved form of a ruthless and corrupt administration. Sisi clearly sees himself in his predecessor and wishes to set a precedent.

Death is the great equaliser, and when Sisi’s day arrives, it will become abundantly clear how equally damaging the two have been for both the short- and long-term wellbeing of Egyptians. Despite the bout of amnesia that has apparently overcome many observers as they compare the two dictators on a scale of callousness - making the “old, frail, sick” Mubarak look like an innocent lamb - we must never forget that he planted the bitter seeds Egypt reaps today.

While financial misappropriation and corruption were hallmarks of the Mubarak era, it was the suppression of the political and civic rights of Egyptians that eventually led to the formidable public awakening against everything he stood for.

Flouting human rights

For the entire duration of his reign - starting in 1981, when he took the helm after the assassination of former President Anwar Sadat - Mubarak ruled under a state of emergency, flouting human rights under the pretext of fighting terrorism. His National Democratic Party completely usurped the public space, run by loyalist businessmen and intelligence officials who maintained a tight grip on all political activity despite the appearance of loosening political constraints.

The emergence of the Kefaya Movement for Change in 2005 and the opening up to opposition media were both forced on him by local and international pressure to hold free and fair elections. But they did not prevent the pervasiveness of police brutality and an unparalleled level of fraud and intimidation during the 2010 parliamentary elections, which many believed would pave the way for his son, Gamal Mubarak, to inherit the throne of Egypt’s oxymoronic republican monarchy.

Mubarak had a clear choice in 2005 to set in motion real political and institutional reform that could have led to a peaceful transition of power. He could have set the stage for a new era of political plurality and accountability as the bedrock of good governance and separation of powers.

But he chose not to do that. Instead, he chose to reinforce his position through repression and condescension based on a sense of entitlement unique to all military dictators around the world.

Too good to be true

I look back on what happened after 11 February, when Mubarak stepped down, and it all makes sense. In August 2011, I was there on the first day of Mubarak’s trial, when the helicopter carrying him flew overhead in an open space brimming with a motley crew of martyrs’ families, journalists, police, lawyers and the odd pockets of Mubarak supporters.

I was there when a big screen perched behind the walls of the vast police academy beamed the now-iconic footage of the ousted octogenarian laid out on a stretcher in humiliation, looking haggard and defeated.

I remember writing an op-ed describing that moment: “It was a moment that simultaneously re-infused confidence in the ‘revolution’ and instilled fear that the long-awaited trial was too good to be true.”

As it turns out, it was too good to be true.

Mubarak was held in a luxury medical facility overlooking the Nile. In the months preceding his so-called “trial of the century”, outrage over the brutality of the premeditated, violent crushing of the peaceful uprising - which by the most conservative estimates claimed 846 lives - had gradually subsided. There was no political will on the part of the SCAF to convict Mubarak on complicity in the deaths of more than 200 protesters in Egypt’s public squares during confrontations with police.

Long way to go

Although Mubarak received a life sentence in the first ruling, he was later acquitted in 2017 and released from custody. A coup had removed Egypt’s only democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, who ultimately died of medical negligence in 2019 during a court appearance - and the “revolution” had come full circle.

The parallel plan to gradually vilify the uprising and the high-profile figures associated with it was played out to the letter. Today, Egyptian prisons hold an estimated 60,000 political detainees, including former presidential candidates. When police officers accused of killing protesters were declared innocent on the grounds that they acted in legitimate self-defence, there was barely a squeak.

Dictatorship did not begin or end with Mubarak. We have a long way to go

I look back at those heady days overflowing with hope for a new Egypt, built on the rule of law and respect for human rights, where justice would be served, no matter who was in the dock.

Back then, I believed that Mubarak’s fall was a cautionary tale to every future president of this country. I was wrong. It was and continues to be a cautionary tale for those who dare to dream of a better future. Dictatorship did not begin or end with Mubarak.

We have a long way to go.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.