US judge gives doctors authority to determine if Guantanamo detainee can be released

A US judge has ordered that a panel of American and foreign doctors be granted authority over whether a Guantanamo Bay prisoner be released or held for continued internment, court documents have revealed.

US District Judge Rosemary M. Collyer ruled on Friday that Mohammed al-Qahtani be examined by a medical commission made up of one medical officer of the US military and two physicians from "a neutral country".

The medical panel will be allowed to determine if al-Qahtani should be transferred to Saudi Arabian custody under a Geneva Convention-based army regulation that outlines the repatriation of sick and wounded prisoners, known as Army Regulation 190-8.

While the regulation outlines the treatment of "prisoners of war", the US government considers those held at Gitmo to be "detainees" or "enemy combatants", not POWs. It is due to that distinction that the regulation, among others, has never before been extended to an individual held at Guantanamo.

But Judge Collyer was clear in her 25-page ruling: "If the mixed medical commission finds that Mr. al-Qahtani qualifies for repatriation, Army Regulation 190-8 mandates that he be repatriated".

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

If the medical panel decides al-Qahtani should be repatriated, then the US must carry out the order "as soon as possible and within 3 months" of being notified, according to the regulation.

'We tortured Qahtani. His treatment met the legal definition of torture. And that's why I did not refer the case'

- Susan J Crawford, head of the military commissions 2007-2010

The Justice Department opposed the motion, but it is unclear if it plans to appeal Judge Collyer's order. The department did not respond to Middle East Eye's request for comment.

The Office of Military Commissions that oversees operations at Guantanamo also did not return MEE's request for comment.

The motion for an army regulation medical panel was filed by al-Qahtani's defence team due to his acute mental health issues. If he is allowed to be released, al-Qahtani will be transferred to Saudi Arabia for psychiatric treatment.

Sometimes referred to as the "20th hijacker", the US government says al-Qahtani was a key player in the planning of the 9/11 attacks against the United States.

In the summer before the attacks, al-Qahtani had tried and failed to enter the US. Months later in December 2001, he was captured during a US operation in Afghanistan's Tora Bora, which was at the time a Taliban-stronghold near the Pakistan border.

Al-Qahtani was transferred to Guantanamo Bay in February 2002.

'Schizophrenia' and 'acute psychotic break'

Before he was captured in 2001, al-Qahtani had been diagnosed in Saudi Arabia with schizophrenia and major depression. He was hospitalised in a psychiatric ward on at least one occasion, according to court documents.

His mental health issues may have been triggered by a traumatic brain injury caused in a car accident he was involved in as a child. Medical records said the accident possibly caused a neurocognitive disorder.

"After that incident, he suffered from 'episodes of extreme behavioural dyscontrol' and 'auditory hallucinations,'" Judge Collyer explained in her ruling, referring to US and Saudi medical records.

"In one incident he was found by Riyadh police in a dumpster and in another he threw a cell phone out of a moving vehicle because 'he believed it was making him 'tired’' and affecting his mind," Collyer continued.

"In 2000, Mr. al-Qahtani was committed to the psychiatric unit of a hospital in Mecca after he attempted to throw himself into moving traffic."

Suffering from an "acute psychotic break", during his hospitalisation he expressed suicidal thoughts and was prescribed antipsychotic medication, court documents said.

Before and after his US capture, al-Qahtani exhibited signs of hallucinations, sometimes hearing and speaking to people who were not there. Reports show that interrogators were aware of his mental health issues early on.

Outside of interrogations, al-Qahtani was kept in isolation for the first 160 days of his captivity, military records have revealed, and was tortured for at least 48 of the first 54 days he was held.

He was repeatedly hospitalised and left in life-threatening conditions during those first months, according to military reports.

Too tortured for trial

Details of the torture he endured were first leaked in an 84-page secret interrogation log obtained and published by Time Magazine in 2005.

Despite the information gaps, the log showed that at times he was chained and forced to stand for prolonged periods, threatened with a military dog, had his head and beard shaved, forced to stand naked, forced to urinate on himself and was deprived of sleep.

Later it was revealed that he was waterboarded, beaten, strangled and forced to endure extreme temperatures and stress positions. Interrogators also tied a leash to his chains, led him around the room and forced him "to perform a series of dog tricks" and bark, reports show.

In 2008, war crime charges against him were dismissed "without prejudice", but not long after military prosecutors said that they would seek to refile charges.

Susan J Crawford, who was the head of the military commissions at the time, said in 2009 that she would not allow the new charges to be filed, excluding him from the joint death penalty case of five suspected 9/11 operatives being tried at Guantanamo's war court.

Crawford said that the US would not seek the death penalty for al-Qahtani because of the torture he had endured at the hands of the US military.

Bush administration lawyers gave legal approval for the "enhanced interrogation techniques", but according to Crawford "the manner in which they applied them was overly aggressive and too persistent".

"We tortured Qahtani," Crawford told the Washington Post in February 2009. "His treatment met the legal definition of torture. And that's why I did not refer the case" for prosecution.

"You think of torture, you think of some horrendous physical act done to an individual. This was not any one particular act; this was just a combination of things that had a medical impact on him, that hurt his health. It was abusive and uncalled for. And coercive. Clearly coercive. It was that medical impact that pushed me over the edge" to call it torture, she said at the time.

Five years after Crawford's statements on al-Qahtani, the Senate's torture report revealed that the other defendants in the joint 9/11 case were also tortured, but so far the case continues, at an albeit slow rate.

The official 9/11 trial is scheduled to start in January 2021, nearly 20 years after the attacks.

War Court: A legal quagmire

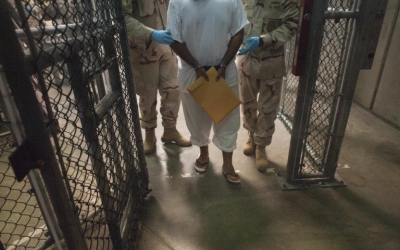

Prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, if charged, are prosecuted on the military base at a special war court, also known as the Office of Military Commissions, with rules and regulations separate from the US's standard justice system.

The Supreme Court in 2006 ruled that the original military commission system violated the Constitution and the Geneva Conventions.

Following the court's ruling, Congress rewrote the rules and passed the Military Commissions Act that same year, creating a new structure for trials by commissions. The act bans testimony based on torture, but permits testimony based on coercion.

In addition to its own court, Guantanamo Bay's prison camp also has its own parole board. Before any prisoners are released, they must get approval from the war court's Periodic Review Board.

The board is made up of representatives from six federal agencies, including the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), which oversees the US intelligence agencies such as the CIA, the agency that developed and lead the torture programme.

The ODNI's participation on the review board has been strongly objected to by defence attorneys who see it as a conflict of interest.

In 2010, the parole board refused al-Qahtani's release and recommended him again for prosecution. The recommendation was not approved by the court.

At more recent parole-hearings in 2016 and 2018, the board determined that al-Qahtani was a "continuing significant threat to the security of the United States", but made no recommendation for prosecution.

The board said it was unable "to assess the detainee's current mindset [Redacted] due to his continued refusal to respond to questions from the Board regarding his reasons for traveling to Afghanistan".

It was after that ruling that Qahtani’s lawyers petitioned the US district court to order the Pentagon to apply Geneva Convention protections to their client, according to the New York Times.

Those protections trigger army regulations for prisoners of war which will allow the joint medical panel to evaluate whether he is healthy enough to continue imprisonment at Guantanamo.

Early in his first term, US President Donald Trump shuttered a mechanism that processes releases ordered by the parole board, leaving little hope for anyone, even those determined to be innocent, to be released.

It was not clear if the release mechanism would be necessary in the case that the medical panel rules in favour of transferring al-Qahtani to Saudi Arabia.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.