Arab-Americans tackling anti-Blackness in the Middle East

Isra El-Beshir, an Arab-American of African descent, attributes most of her encounters with racism in the United States to people of Middle Eastern backgrounds.

"I've never once experienced any overt racism from white Americans, ever. It was the word 'abeed' - that was the first time that I came face-to-face with it - from the mouths of Arabs and Muslims primarily," she told Middle East Eye.

"To me, confronting that and realising that my membership was limited, was a wakeup call."

For Black Arabs such as El-Beshir, anti-Black racism and colourism are part of reality. "Blackface" is a common sight in Arabic comedy shows and the racial slur "abeed" - or slave - continues to occupy a space in the vocabulary of many non-Black Arabs.

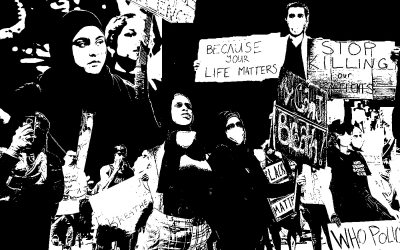

A group of Arab-Americans now wants to start a conversation on this uncomfortable truth within their community with renewed urgency, given the global movement sparked by the death of George Floyd, a Black man, in May.

Floyd's brutal treatment at the hands of a white police officer in Minnesota sparked outrage and protests around the world - while his death followed a phone call from an Arab-American-owned store to alert the police.

Instead of tiptoeing around the subject, they want to confront anti-Black racism head on, saying the stakes of doing nothing are too high to be ignored.

"Black people are dying because we don't say: 'What does it actually mean that I'm calling the police every time I perceive that a Black person is making me feel threatened?'" Rana Abdelhamid, a community organiser from Queens, New York, told MEE.

"There's no time to wait. The fact that we don’t ask these questions kills people."

Arab colour divide

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement has lifted the veil on the social, political and legal discriminations faced by Black people in the US.

It has also shone a spotlight on discrimination against Black people globally, including the position Black Arabs hold within predominantly non-Black Arab communities, according to El-Beshir, a cultural anthropologist.

"Afro-Arabs, Black Arabs within their native 22 Arab countries, are not often recognised and are dealing with their own set of issues of being marginalised, oppressed, racialised and so forth," El-Beshir told a digital townhall hosted by the Take On Hate campaign.

'Afro-Arabs, Black Arabs within their native countries … are not often recognised and are dealing with their own set of issues of being marginalised, oppressed, racialised'

- Isra El-Beshir, Afro-Arab cultural anthropologist

In the US, many Arab-Americans find Black Lives Matter a difficult topic to raise within the Arab community, which itself has been on the receiving end of sustained Islamophobia.

"People tend to think: 'I’m experiencing oppression and violence. I can’t think of other people because I’m already carrying too much of a load,'" said 27-year-old Abdelhamid, who is a long-time social justice activist.

When Abdelhamid's parents lived in Egypt, a multiracial society, they "internalised colourism and anti-Blackness” along with a certain perception of Black people, she said.

"When they came to the US, there was an added layer, which was the narrative that criminalises Black people, that portrays Black people in a negative light, which has attributed to the way Black people are treated today," she explained.

A process of 'unlearning'

Abdelhamid encourages Arabs to learn more about anti-Black racism within their own cultures and explore their role in perpetuating it. She and her friend Mafaz Al-Suwaidan created a social media "toolkit" in both English and Arabic offering step-by-step guidance on how to begin the process.

"There has to be an unlearning of what they learned in the Middle East and North Africa [about Black people], and an unlearning of what they've learned here in the United States," she said, adding that the post had gone viral and that many people had asked for it to be translated into a variety of languages.

The more conversations people have about anti-Black sentiments, the more apparent it becomes that the problem transcends borders, cultures and ethnicities, say activists. Asian- and Latino-Americans are among other minority groups in the US who have launched similar initiatives to support BLM and confront anti-Black prejudice in their own backyards.

Lingering remnants of slavery

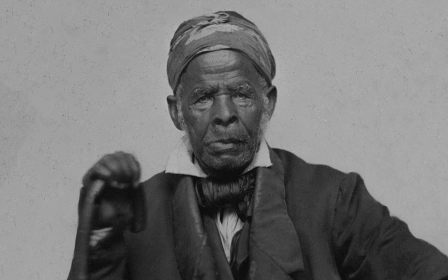

In order to comprehend why anti-Blackness is prevalent in Arab societies, one must begin by recognising the region's own "skeletons in the cupboard", such as its long history of slavery and colonialism, said historian and author Dele Ogun.

For more than a millennium, beginning with the Arab conquest, the slave trade across the Sahara desert has been responsible for transporting millions of people from sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa and the Middle East.

While the trans-Atlantic trade that forcibly uprooted Africans to slavery in the New World was bigger in intensity and much more publicised, the trans-Saharan route was longer-running, and there’s evidence that it has never stopped, according to Ogun.

"The explanation for this is colonisation, in that the trans-Atlantic [slave trade] was first a response to, and then was fed by, European expansion into new lands," said Ogun, who’s currently working on a new history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

"Through this process, new identities were created for the enslaved, as African-Americans, African-Caribbeans etc.

"The Arab states had no new colonies to fill up and develop with slave labour and simply absorbed those they took.

"It also meant that they did not have the same fears of losing their territories to the Africans once liberated, as happened in Haiti, which was the mortal fear that white America had, and to a lesser degree the British in Jamaica," he told MEE.

Hence, while the trans-Atlantic slave trade was abolished in the early 19th century, it took much longer for many Arab states to outlaw slavery, with Mauritania being the world's last country to do so in 1981.

Activists say slavery still thrives in the modern-day Middle East and North Africa, notably manifesting itself in the form of kafala, the sponsorship system which brings migrant workers to the region and ties them to one single employer.

Kafala has been linked to numerous cases of migrants' abuse and death in Arab states and activists have been calling for its abolition.

Then there's Libya, where Black youths have reportedly been sold at "slave markets". Critics say the country has long been known as a hotbed for human trafficking, exploiting African migrants who try to cross to Europe seeking a better life, but little has been done to tackle the problem.

Arab identity and priority

In the US, Arab-Americans are legally recognised by the US census as white, which has both legal and social implications for Afro-Arabs.

"When we look at it from the legal perspective, Arab-Americans for various reasons have achieved liminal whiteness, situational whiteness for the most part," says El-Beshir.

"Then you have experiences of Afro-Arabs or Black Arabs, or Arabs of darker pigmentation, who might socially be categorised as Black in this country and who have a completely different experience.

"So that in many ways exacerbates the Arab-American experience for various reasons," she added.

'Those of us who identify as Arab … feel erased from the [dominant Arab] narrative. We feel that in many ways we have to defend our identity as Arabs'

- Isra El-Beshir, Afro-Arab cultural anthropologist

"Afro-Arabs bear much of the burden of having to prove their 'Arabness' and defend their racial and ethnic alignment and, at the same time, [non-Black] Arab-Americans are navigating their own issues concerning Americanness and liminal whiteness, so we have different priorities," El-Beshir noted.

The wide gulf in the treatments of Black and non-Black Arabs is evident starting from a young age, especially through school curricula and educational systems that perpetuate anti-Black stereotypical representations.

Speeches relating to the image of Black African communities in the Arab world bear witness to the violence of racist prejudice and the extent of the stigma.

"It is enough to take a quick look at the content of the books recommended in the context of teaching, whether in middle or high school, to realise the damage caused to mentalities," said Salah Trabelsi, an academic and a member of the International Scientific Committee for Unesco's Slave Route Project.

Excluded from the Arab narrative

While discrimination is felt by most Arabs in various forms, not all sympathise with the plight of Black Arabs in a white-dominated world.

"Those of us who identify as Arab feel disrupted based on the limited categorisation that exists in the US and also feel erased from the [dominant Arab] narrative. We feel that in many ways we have to defend our identity as Arabs," El-Beshir told the panel discussion.

The Black Lives Matter movement addresses systemic issues affecting African-Americans disproportionally, which are also affecting "a group within the Arab-American population who are often unrecognised", El-Beshir said.

"With this movement, you see many more Africans in diaspora associating with African-Americans and at the same time calling out Arabs on some of the issues that exist within the culture that is race-based, anti-Blackness, the colourism that exists that may manifest in different ways.

"So what role does the Arab-American play in perpetuating racist, anti-Black ideas?" she asked.

'We're all connected'

Arabs in the US may not always be aware that they are, to a degree, direct beneficiaries of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

The passing of the seminal Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 - on the heels of other major civil rights legislation - paved the way for a new wave of Arab immigration, including Arab Muslims.

Up until then, immigration to the US was primarily reserved for Europeans - and mainly Christians.

Because of the 1965 act, Abdelhamid's parents and other Arab Muslims were able to move to the US with a chance to build a new life.

If the Arab community ignores the connections between the liberations of Black and Arab people, there's a dangerous possibility that "structural issues deeply rooted in anti-Blackness and slavery" may get woven into government legislation, Abdelhamid warned.

"All of our work is interconnected - I will not solve the problem in the Middle East unless I fight it here [in the US]," she said, adding that right now was a "soul-searching time for anyone who's not Black".

"It's the medicine I know you don't want to take, but you have to take it because it's necessary."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.