Former soldiers angered by UK plans for Iraq war crimes 'amnesty'

Concerns are growing among human rights groups and ex-soldiers about UK government plans for a new law to protect British soldiers from prosecution for any acts of murder or torture committed after the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

The draft law, known as the Overseas Operations Bill, proposes to prevent service personnel from being prosecuted for any crime committed more than five years earlier, other than in exceptional circumstances.

It would also protect British forces from prosecution in the UK for war crimes or crimes against humanity once those crimes were more than five years old.

The measures have alarmed NGOs who fear that any weakening of the criminal measures against torture would undermine the UK’s commitment to the Geneva Conventions.

Redress, a London-based charity that works with torture victims, says there is a risk that abuses will be “swept under the carpet”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The bill risks creating an effective amnesty for serious offences including torture, according to Chris Esdaile, the organisation’s legal adviser.

“The UK’s international treaty obligations require serious international crimes always to be prosecuted. The UK has promoted these obligations for over 70 years,” said Esdaile.

Another London-based NGO, Rights and Security International, warned that the new law could create “a culture of impunity” for British forces serving outside the UK.

'A stain on Britain's standing'

The proposed new law has also angered many former soldiers, who argue that the proposed new protections are dangerous and demeaning.

Charles Guthrie, a former field marshal who was head of the UK’s armed forces from 1997 to 2001, has warned that the bill “provides room for a de facto decriminalisation of torture” and that its provisions “would be a stain on Britain’s standing in the world”.

In a letter to the Sunday Times newspaper, Guthrie wrote: “My military experience taught me the horror of torture. It is evil and must be punished wherever perpetrators can be found. Every good soldier knows that to be true.”

Nicholas Mercer, a former lieutenant colonel in the British army, who was the most senior military lawyer in Iraq following the 2003 invasion, said: “This bill is a deeply retrograde step by the British government. It undermines, not only the UN Convention against Torture, but also the Geneva Conventions 1949. This is simply unprecedented.

“Having used inhuman and degrading interrogation techniques during the Iraq conflict, the British government is now arguably seeking to legislate to avoid liability, whilst maintaining that the claims are unfounded.

“There also remains the unanswered question of ‘black sites’ in southern Iraq and the fate of prisoners who were taken there by UK Forces. This bill may mean that such cases never see the light of day.”

A consultation document that the British government published last year suggested that sexual offences and torture might be specifically exempt from the new law.

However, when the Overseas Operations Bill received its first formal reading in parliament, just as the UK was about to go into coronavirus lockdown, sexual offences were exempt but torture was not.

Dominic Grieve, a former Attorney General for England and Wales, quickly pointed out that a British soldier who had raped, tortured and murdered another person more than five years earlier could still face prosecution for rape but, under the new law, would be unlikely to be prosecuted for torture and murder.

This shows “how difficult and potentially unsatisfactory it is to try to use legislation to skew a legal system to give privileged protection to a particular group”, Grieve says.

Another anomaly that would be introduced by the proposed law is that a soldier could still face prosecution, under military law, for offences against a fellow soldier, but would be protected from prosecution after five years if the offences were committed against a civilian.

Protection for ministers

In its consultation document, the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MoD) said it was determined to draw a line under criminal probes, after a number of servicemen found themselves being repeatedly investigated over several years.

Few soldiers have faced courts martial or criminal trials however, and even fewer have been convicted.

The bill also offers new protections from civil compensation claims for government ministers and the MoD.

The MoD also says that it wants to bring an end to what it describes as “lawfare” - compensation claims that it says it has faced “on an industrial scale”.

As of 2017, the MoD had paid out £22 million to settle 1,471 claims from Iraqi nationals who had alleged they had been mistreated or unlawfully detained.

Those who have lodged claims against the MoD include the family of Baha Mousa, a Basra hotel receptionist who was tortured to death by British troops in September 2003.

Why was the British Army in Iraq and Afghanistan?

+ Show - HideThe UK sent forces to Afghanistan as part of the international coalition that invaded the country in 2001 following the 9/11 al-Qaeda attacks in the US, and to Iraq in 2003 as part of a US-led invasion to overthrow Saddam Hussein.

In both countries British soldiers became increasingly bogged down fighting against insurgents opposed to international occupation.

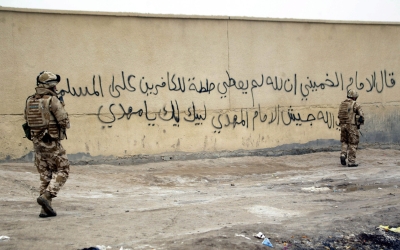

In Iraq, British forces were handed responsibility for security in Basra and three provinces in the south, but their presence was challenged by Muqtada al-Sadr’s Mahdi army militia fighters.

In September 2007, British forces withdrew from their bases in the city to the airport on the outskirts, the targets of “relentless attacks”, according to an International Crisis Group report which said that their retreat was viewed by locals as an “ignominious defeat”.

In Afghanistan, British forces had been deployed in 2006 to Helmand Province. But they proved ineffective against the resurgent Taliban and in 2009 more than 100 British soldiers were killed.

British troops eventually withdrew from Afghanistan in 2014, with 454 service personnel killed over the course of their 13-year campaign in the country.

Part of the incident was filmed. Six soldiers were court-martialled for the abuse of Mousa and six other Iraqi men, but were then cleared. One soldier pleaded guilty to inhumane treatment of a prisoner, and was jailed for a year and dismissed from the army.

Mousa’s death was later the subject of a lengthy public inquiry.

Critics say the part of the proposed new law that introduces time limits for civil claims will protect government ministers and senior defence officials, rather than ordinary soldiers.

Esdaile said: “The civil claims for compensation in relation to such human rights violations have been brought against the Ministry of Defence, not against ordinary soldiers.

“When overseas operations involve abuses by British armed forces, most service personnel find these abuses as abhorrent as everyone else. This bill does nothing to facilitate the accountability of politicians and high-ranking military personnel who give the orders.”

Yasmine Ahmed, spokesperson for Rights and Security International, added: “Rather than dismantling the system of accountability for abuses committed by the UK military, the government should be painstakingly reviewing the recommendations that came from inquiries such as the Baha Mousa Inquiry and ensuring that such abuses, including unlawful killing and torture, never happen again.

“Cultivating a culture of impunity and erecting barriers to accountability is not the answer.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.