Coronavirus-hit Hebron struggles with social stigma and Israeli occupation

Walk around the streets of Hebron, and you'll likely hear people greeting each other with the same refrain: “I will kiss you on the cheeks despite corona.”

It's a phrase that is becoming increasingly concerning for authorities in the occupied West Bank's largest city.

Hebron has been hit hard by the second wave of coronavirus, which emerged in early June after it seemed the West Bank had got through the worst of the pandemic. This week alone, a 12-year-old girl, three women and a 90-year-old man died of Covid-19.

Overall, the Palestinian territories have had a relatively low death rate, with 47 fatalities compared to Israel's 371. But the number of cases is rapidly rising, with 8,153 infections in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip recorded since March.

'People still deal with the coronavirus pandemic as if it does not exist and is part of a global conspiracy, and this led to the spread of the virus'

- Tayseer Abu Sneineh, Hebron mayor

Mai al-Kaileh, the Palestinian Authority’s health minister, said 27 active coronavirus hotspots had been identified in the West Bank, in villages, refugee camps and cities.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Kaileh said 111 Palestinians are currently hospitalised, seven of whom are on ventilators in intensive care.

Hebron, a socially conservative city divided by the Israeli occupation and functioning as the West Bank's economic powerhouse, is a microcosm of the challenges Palestinians face as they try to ward off coronavirus.

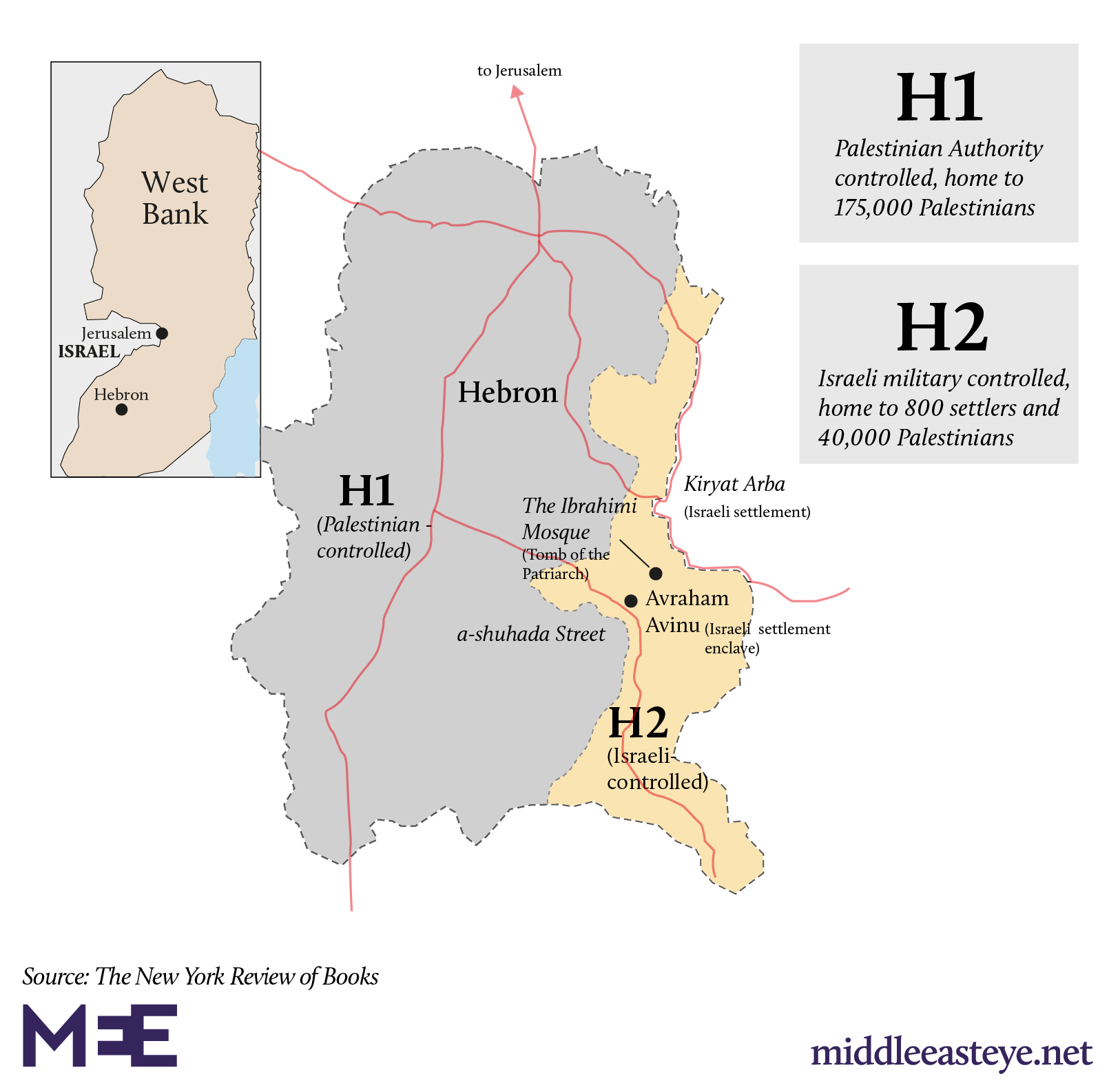

The city is effectively cut into two parts according to a 1997 agreement signed between the Israeli government and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation.

Hebron is divided between H1, under the full administrative and security control of the Palestinian Authority (PA), and H2, administratively run by the PA but controlled by the Israeli military, which has the final say on who enters and who exits the area.

Tayseer Abu Sneineh, mayor and head of Hebron municipality, told Middle East Eye that this divide has proved a challenge for medical staff battling the pandemic, with ambulances often obstructed from entering H2, where some 40,000 Palestinians live adjacent to 800 Israeli settlers.

H2 has 18 permanently staffed Israeli military checkpoints.

“The Israeli occupation, in general, is an obstruction to the development of the city and it controls the border and water and everything. Not a single bed was added to the Hebron governmental hospital since the occupation in 1967, until the Palestinian Authority started handling the city in the 1990s,” Abu Sneineh said.

Currently, there are several hospitals in the Hebron district that deal with coronavirus patients, including the Red Crescent Hospital in Halhul and Dura Hospital, which was opened before its scheduled date in June. A section is being prepared to open in Hebron Governmental Hospital as well.

Together, these hospitals serve the 215,000 Palestinians living in the city and its surrounding villages, an area that that has almost 120 Israeli military checkpoints. According to Abu Sneineh, 120,000 Palestinian Hebronites live in areas that have no clinic or even police station, and the prevalance of checkpoints hinders their access to the district's hospitals.

That said, PA policies and public responses to the pandemic have only added to an already difficult situation.

In March, the PA placed the West Bank under full lockdown until the end of May, resuming it for nine days in June as cases began to spike again.

But Hebron, the territory's manufacturing hub, never really adhered to the restrictions, and now it is feeling the effects.

“Unfortunately, some people still deal with the coronavirus pandemic as if it does not exist and is part of a global conspiracy, and this led to spread of the virus,” Abu Sneineh said.

Hebron municipality has set up an emergency centre to coordinate its response, and published brochures and leaflets to caution against Covid-19's deadly risk, but with little cut-through.

On 11 July, authorities called for social distancing measures to be respected as it announced the results of the secondary education examinations, but many people instead crowded into cars and toured the city in celebration.

“We, the Palestinian people, have something in our character, which is the spirit of the challenge. Of course, challenging the occupation is positive, but to challenge a virus this way is something negative,” Abu Sneineh said.

Bashar al-Atrash, a resident of H1 who works in food manufacturing, told MEE that he returned to work in a factory after respecting 20 days of the first lockdown.

For Atrash, coronavirus is perplexing because so many people who tested positive did not show any symptoms.

"We heard about corona in the media and from officials and from the mosque, which after the prayer call made an announcement telling people pray at home," Atrash said.

'We, the Palestinian people, have something in our character, which is the spirit of the challenge. Of course, challenging the occupation is positive, but to challenge a virus this way is something negative'

- Tayseer Abu Sneineh, Hebron mayor

"What is this virus that doesn't give you a cough, headache, stomach ache, fever or diarrhoea? Five of my relatives have been told that they've tested positive of coronavirus, and when I went to visit them in their house after they left the hospital, they looked healthy and fine. So, what's corona?"

Atrash shared with MEE a message that has circulated on social media in Hebron, written by an alleged doctor that presented a "cure" for Covid-19, which is to thinly cut a small onion and eat it raw two times a day during meals.

The message said the "actual experiment proved ... that is sufficient to protect you from coronavirus and respiratory viruses, no matter how strong and without taking precautionary measures".

Atrash added that he tried this "cure", but added one clove of garlic upon an advice from a relative.

When the pandemic hit the Arab world in March, many similar messages spread on social media.

The most famous false remedy promoted was during a TV interview with an Egyptian doctor, who claimed a cure for coronavirus already existed in shalawlaw, a Coptic meal eaten during the fast of the Virgin Mary made from dried molokhia, garlic, cold water, lemons and spices.

"We don't know who to believe, the government, or the media, or the officials? Everyone is taking his own initiative to protect themselves," Atrash said.

Meanwhile, Hebron remains open, with visitors coming from the Palestinian Bedouin community inside Israel's Negev, East Jerusalemite families who have roots in the city, and Palestinian citizens of Israel from towns such as Oum al-Fahim, Nazareth, Kafr Qasim and Kafr Kanna, who come to shop and pray in the historic Ibrahimi Mosque.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.