Venice Film Festival: Middle East movies return

It was only a few months ago that the mere prospect of organising a full physical film festival form was deemed far-fetched. Sitting in a movie theatre with industry, press and public in a single, closed vicinity again was rendered the stuff of the imagination.

From March, all major film festivals – Cannes, Karlovy Vary, Locarno and Telluride – were cancelled, while smaller scale fairs such as Visions du Réel in Switzerland, CPH:DOX in Denmark, and Sheffield in England were held strictly online.

Given how hard Italy was hit by the coronavirus, film insiders expected that Venice would follow suit. From the get-go, however, the festival’s director, Alberto Barbera, repeatedly insisted that the A-list event which, along with Toronto, is traditionally when many of the awards seasons contenders premiere, would go ahead.

Yet despite the rising number of infections in recent days across Europe, the 77th Venice International Film Fest, or La Biennale di Venezia, kicked off on Wednesday, becoming the first major film event to be held physically since the outbreak of the pandemic - albeit in an almost unrecognisable form and with the most atypical lineup in its recent history.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But the selection has still found space to include features from the Middle East and North Africa.

On opening night, directors of the eight major European festivals – Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Karlovy Vary, Locarno, San Sebastian, Rotterdam and London - recited a shared statement underlining the importance of film festivals in preserving cinema against the threat of streaming services, with the latter having increased their influence and revenues during lockdown, as many films go straight to streaming rather than cinema.

As cinema continues to grapple with an uncertain future, the statement came as both a reassuring stance of solidarity with the filmmakers and a call to arms by all film industrials to protect the cultural experience that is movie-going.

The initial prediction that the selection would be a largely European affair was dismantled with the announcement of a scaled-back lineup that includes titles from across the globe. Despite the European Union’s strict travel ban, a handful of international guests have been allowed in, if under stark stipulations.

The red carpet, meanwhile, has no fan zone and a 2.5 metre wall has been erected

The number of guests has been slashed in half, with the press and industry delegations largely restricted to Europe. All international guests outside the EU were obliged to conduct a Covid test 72 hours prior to their arrival in Venice. Further tests were required if they wanted to stay.

Entry to the festival area was limited and thermo scanners installed. Sanitisers and disinfectants are on offer everywhere you look. The red carpet, meanwhile, has no fan zone and a 2.5 metre wall has been erected to separate the celebrities and others entering venues from everyone else.

Masks have been made mandatory. Social distancing markers are all around, including the red carpet. The mood thus far has been dominated by quiet anticipation and predictable unease. Masks of every colour and texture have made the faces of colleagues and acquaintances difficult to recognise.

Even with all the restrictions, returning to festival screenings in big halls with large groups of people did not feel as unusual or disconcerting as one might assume. On the contrary, there’s something somewhat life-affirming about going back to the movies in such a large setting after months of uncertainty regarding the fate of the festival circuit in particular, and cinema in general.

No Netflix, little US

The trimmed-down lineup of the festival stands worlds apart from the stuffed, star-studded selections of the past. While Cannes took a firm stance over the past couple of years against including any Netflix productions following the backlash of French theatre exhibitors, who boycotted the streaming giant for reducing the window between films’ release in cinemas and online, Venice kept the door to the network wide open.

Eight out of the 18 films in competition are directed by female filmmakers – unprecedented in Venice’s history

This year, a whooping eight out of the 18 films comprising the competition (44 percent) are directed by female filmmakers – an unprecedented feat in Venice’s history

While not bereft of stellar works from around the globe, Venice has grown Hollywood-heavy since Barbera returned as director in 2011. Venice was, after all, the launchpad to some of the biggest Oscar successes of the past decade – a list that includes Joker, La La Land and The Shape of Water.

A notable beneficiary of this gap are women filmmakers. For years, the Venice competition has been staunchly criticised for shunning female filmmakers, averaging one in selections of 18-22 over the past six years.

Another big difference this year was that American players such as Amazon, Apple and Netflix deciding to forgo festival season. This year’s completion is a restrained affair, missing the dazzling star wattage of an average Venice edition.

Also faring well this year, though less likely due to the restrictions than to developments in the region's cinema industry, are selections by Middle East directors.

Middle Eastern movies have been a staple fixture in Venice’s recent history, with some of the region’s biggest hits premiering in the different strands of the festival: Lebanese Ziad Doueiri’s The Insult (2017), Saudi Haifaa al-Mansour’s The Perfect Candidate (2019), and Turkish Emin Alper’s Frenzy (2015), all in competition, and Soudade Kaadan’s The Day I Lost My Shadow, in the Horizons section.

This year is no different, with various prominent productions from across the region participating.

Among the anticipated Middle Eastern pictures showing over the coming week are veteran Iranian director Majid Majidi’s adventure drama, Sun Children, in competition; Tunisian Kaouther Ben Hania’s refugee satire, The Man Who Sold His Skin, starring Monica Bellucci in Horizons; Ismael el Iraki’s Moroccan punk romance, Zanka Contact in Venice Days; Palestinian brothers Tarzan and Arab Nasser’s minimalistic comedy, Gaza Mon Amour, also in Horizons, among several others.

Flailing identities

The stage was set for the Middle Eastern selection with Honey Cigar, the feature debut from French-Algerian director Kamir Ainouz which opened the Venice Days sidebar – the first time a debut by a female filmmaker has had this honour.

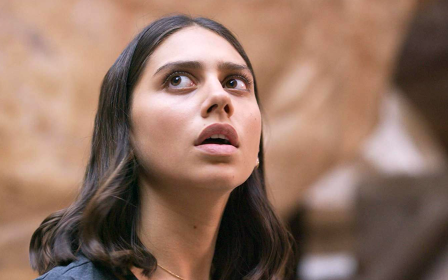

Set against the backdrop of the Algerian Civil War, Zoe Adjani – in a remarkably mature star-making performance – plays Selema, a fierce 17-year-old Parisian college student raised and living in the French capital to immigrant bourgeois Algerian parents torn between their newly constructed identities and their abandoned homeland.

Although Parisian through and through, Selma finds in her flailing Algerian roots a different identity from the rigid one ascribed to her by both her peers and her instructors.

Neither fully French nor genuinely Algerian, the bright Selma struggles to navigate her way into adulthood while battling the hypocritical traditions of her parents and the overriding sexism of her privileged French milieu. Along the way, she discovers sex, which becomes not only a missing piece of her budding identity, but a means to attain her autonomy.

Most problematic is the relationship of the parents, which suffers from palpable lack of development and glaring gaps

Inspired by the director’s childhood, the story of a second-generation European Arab with an identity crisis is not exactly fresh terrain for a debutant filmmaker; nor is the coming-of-age account of a pre-#MeToo young woman struggling to explore her sexuality in a chauvinistic, entitled culture. And yet, for the most part, Honey Cigar works.

Ainouz recreates her bourgeois teenhood with commendable sensitivity and honesty, capturing the contradictions between the parents’ Algerian heritage and their ambitious class aspirations with intelligence and thoughtfulness.

It’s also refreshing that for once, sex is being depicted as a joyous, self-empowering tool and not in the common forlorn, dangerous light. The backdrop of the civil war, however, never fully comes to life. Most problematic is the relationship of the parents, which suffers from palpable lack of development and glaring gaps.

At 100 minutes, Honey Cigar, feels truncated. Relationships are suddenly cut short and resumed with insufficient conviction; motivations behind the behaviour of some of the characters (especially the parents) are unclear; while plenty of the unfolding action is rushed and never given room to breathe. There’s certainly a superior, more complete film out of this material...just not this current version.

Istanbul, up close and personal

Far more accomplished is Turkish director Azra Deniz Okyay’s auspicious debut, Ghosts, premiering at the Critics’ Week sidebar. Taking place during a single day amid a looming nationwide power outage, this multi-character drama follows the intertwining lives of four different characters navigating the nightmarish urban jungle of Istanbul.

One is a middle-aged working-class mother seeking to gather the finances needed to bail her son out prison; another is a modern dancer who seeks shelter from the destitute reality of the city in the underground music and queer scene; a third is a determined feminist activist battling an unconquerable system; and the last is a hustling middleman trading in whatever he can. All four stories are set in a neighbourhood undergoing radical gentrification – an embodiment of Erdogan’s failed neoliberalism.

Independent Turkish cinema has experienced a seismic shift since the 2016 military coup attempt, which led to increased censorship, drying up of funds, and restrictions on co-production. Subsequent productions fall under two categories: family dramas set in the countryside; and period pieces. Realistic depictions of urban life have become increasingly infrequent as filmmakers continue to struggle over where exactly to draw the line with the censorship.

Ghosts hits like a lightning bolt: a gritty, angry portrait of a decaying city evolving into countless confusing directions and descending into darkness

It means that Okyay’s piece hits like a lightning bolt: a gritty, angry portrait of a decaying city evolving into countless confusing directions and descending into darkness (the power outage is an obvious metaphor for this theme).

Simply put, Istanbul has been rarely seen in such raw, unadorned fashion. This is the metropolis of the nascent queer scene; of suppressed underground art; of Syrian refugees running small businesses and populating dingy hostels; of the drug traffickers and corrupt police and resilient activists; of a diminishing middle class that has been driven deeper into poverty.

None of the stories contain tangible narrative arcs. The characters simply glide, floating from one depleted corner of the city to the next, orbiting each other’s lives without fully entering them.

Okyay is shrewd enough not to point the finger at a specific culprit for all of the city’s malaise. The marginalised Istanbul lives she paints have been forced to exist in the shadows, where hope and deliverance are impossible to attain. Small transient acts of kindness keep them afloat to withstand more frustrations, more injustices, more disappointments, to survive another day.

Brimming with visual vitality and immediacy, Ghosts is, hands down, one of the most distinguished Turkish debuts in recent years, and the highlight of Venice’s Middle Eastern selection so far.

A world apart

Less successful is Ameen Nayfeh’s debut feature, the Venice Days contender 200 Meters, a road movie about Moustafa (Ali Suliman), a construction worker from the West Bank residing a few miles away (hence the title) from his Arab-Israeli wife and kids who live on the other side of the separation wall.

Relying on occasional work permits to enter Israel and spend time with his family, Moustafa is constantly absent from the household – a situation not improved by the stagnant economic situation. When his son is injured in a car accident, Moustafa embarks on a treacherous journey with a group of Palestinian men to cross illegally into Israel, accompanied by a mysterious German woman filmmaker who ventures to document their toils.

Nayfeh sets the stakes high with a great concept that resonates far beyond Palestine. The expanding borders between nations and the taxing price lovers, friends and families are forced to pay as a consequence has never been as relevant as it is today, especially in the Covid-19 age.

The first part of the film is particularly riveting in its demonstration of the absurd daily realities of a family living so close yet so far from each other. The introduction of the German filmmaker and the ensuing mishap that occurs when the smuggling job is carried out turns the story into a thriller of sorts, and for a short period, the story becomes brilliantly tense.

200 Meters ultimately feels underwhelming; frustratingly tame, unambitious and strangely safe

Nayfeh, alas, fails to sustain this, as the drama – which is further hampered by mundane visuals – takes the predictable, well-trodden route of social realism, killing the rhythm and squandering its great initial premise.

At the heart of the narrative is a brilliant, original idea that begs for a more philosophical, adventurous narrative that would allow it to take flight, go wild, and travel a less predictable path, especially since the story does veer from reality in parts.

Instead, Nayfeh chooses not to take risks. The result is that 200 Meters ultimately feels underwhelming; frustratingly tame, unambitious and strangely safe. There are several moments of real emotional power that makes the film riveting at times; by the end though, it feels like a wasted opportunity. But despite its serious flaws, strong commercial potential beckons.

Wasted chances

More underwhelming was Iranian Ahmad Bahrami’s The Wasteland, which premiered in the Horizons section. Another directorial debut, the drama is a stark, black-and-white chronicle of the last week of a dying community of brick makers whose remote bankrupt factory in an unidentified village is being shut down after 40 years.

Adopting a Rashomon-like structure in examining the impact of the factory closure on the workers, the narrative of the story teases with the promise of big revelations, muddled secrets and dysfunctional relationships that would open up this clandestine world to viewers.

What we ultimately get instead is esoteric imagery and stiff posturing swaying between pretentiousness and self-seriousness without offering anything illuminating or substantial at the end.

Pointlessly oppressive and humourless, the beautiful landscapes and atmospheric cinematography cannot save an empty picture that is neither a thoughtful, profound study of a closed community on the brink of extinction, nor a fable of a powerless people with Stockholm Syndrome, fighting to break free from the mental chains their despotic leader has entrapped them with for decades.

During the weekend, more guests are expected to descend on the Lido. Deals in the smaller market are expected to be forged, and countless reports about what the return of the European festivals could mean will be written.

The future of cinema is still up in the air but the sheer fact that festivals are still able to happen has injected film industry types and critics alike with cautious optimism. Anything could happen in the next week, and maybe, just maybe, cinema may not be forced to throw in the towel just yet.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.