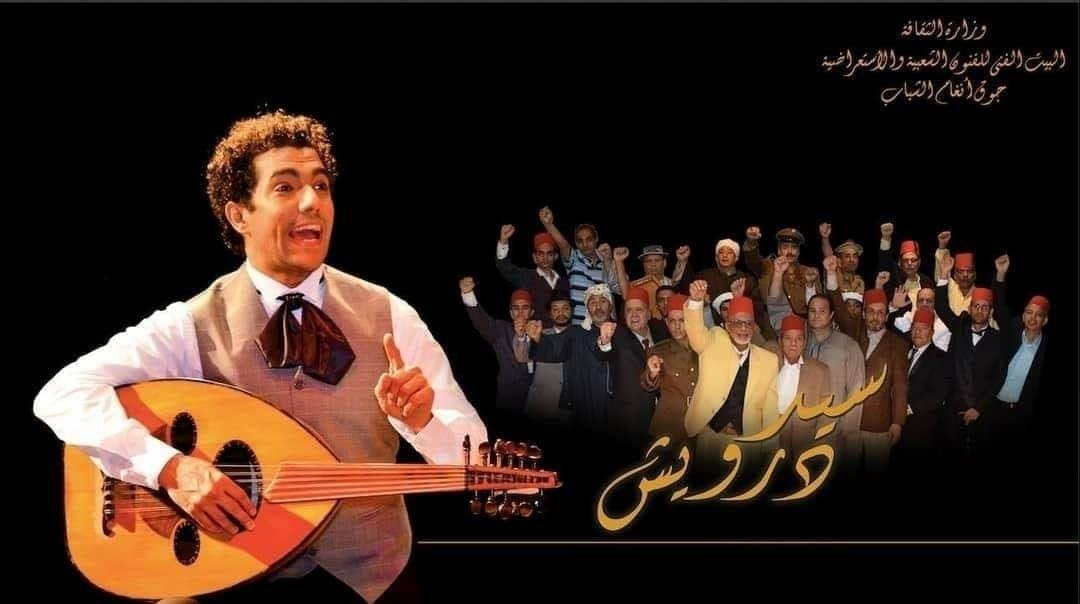

Egypt: Censorship targets patriotic songs of iconic singer Sayed Darwish

Egypt has banned more than a century old patriotic songs composed by the iconic musician Sayed Darwish from being performed at a recent musical, in a step described by free speech advocates as an attempt to censor artistic heritage.

The show - entitled The People’s Artist: Sayed Darwish - has been produced by a culture ministry affiliate and performed at a government-run theatre in Cairo since the first week of August.

The play depicts significant parts of the life story of the Alexandria-born musician, highlighting the hardships the artist went through to be heard and recognised. It links the different historical phases he underwent throughout his short-lived career during the British occupation to the songs he composed and performed at the time.

The script primarily included two popular songs by Darwish: Ya Balah Zaghloul (O, Red Dates) and Aho Dah Elli Sar (This is What Took Place) that have historical connotations. However, the theatre attendees were surprised to find the first song and a whole couplet of the second removed from the script.

The use of Ya Balah Zaghloul may have sarcastically hinted at Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi who had been nicknamed "Balaha" (a date) by his opponents after a funny character - who appeared in a single scene in an Egyptian comedy - personifying an arrogant madman admitted to a mental health institution.

Known to be a source of worry for both the monarchy and the British occupation at the time, Darwish was an innovator who swam against the commercial musical current, introducing new types of songs that boosted the morale of Egyptians artistically.

Ironically, his songs - which are still heard and performed today - apply to the suppression and bitter reality that people are currently surviving in Egypt. The present national anthem of Egypt was composed by Darwish, another proof of his worth.

To this day, the actual cause of death of Darwish - a subject of conspiracy theories - at the age of 31 remains a mystery.

Banned but not forgotten

Historically, Ya Balah Zaghloul was sung by singer Naima el-Masriya and written by the late, renowned multi-talented writer Badie Khairy to refer to political leader Saad Zaghloul who had been banished to Malta by the British occupiers in the early 20th century.

The mere mention of Zaghloul’s name was politically and legally banned in Egypt at that time. That is why Egyptians would refer to their popular leader by the song that Darwish made especially for him.

During the show, the actor personifying Darwish, Mohamed Adel, sang the first line of Ya Balah Zaghloul, followed by music, without words, played in the background with the lights off until it was over. Yet audiences would sometimes cheer and sing the song.

Social media users were quick to react to the ban. The hashtag “balah zaghloul” was trending for days, mocking the decision believed to be taken as per the directives of Sisi, known for being intolerant to any kind of criticism.

Abo Hazem tweeted: “Aren’t you upset with the… song… we will disseminate it more… we will support whatever upsets… you balaha… balaha… balaha…”

Another user named Mohamed el-Kholy wrote sarcastically on Twitter addressing Sisi: “Had Sayed Darwish been alive [today], you would have arrested him because of this song.”

This was not the first time the mention of the fruit seems to have angered Sisi.

In March 2018, filmmaker and photographer Shady Habash and six others were arrested two days after the release of a video of a song entitled Balaha that satirised Sisi. Ramy Essam, who is currently in self-exile in Sweden, performed the song. Shady Habash later died in Tora prison in May 2020.

Habash was accused of being involved in a terrorist organisation, misusing social media tools and offending the military institution. He was kept in pre-trial detention for over two years until he died in custody under suspicious circumstances.

Even though the song, released during the time of Sisi's re-election, was artistically weak, it attracted more than five million views on YouTube only after the arrests of its makers.

In the song Aho Dah Elli Sar, meanwhile, the couplet “How could you blame me, sir, while our fortunes are not in our hands? Tell me about things that would benefit us; then you can blame me,” mainly cites how Egypt’s fortunes were not being used for the welfare of citizens throughout the British occupation. It is believed to also echo the reality Egyptians are surviving now.

Also written by Khairy, the song has been quite popular in Egypt and the Middle East for decades. It was performed by several famous singers over the years, including the legendary Lebanese singer Fairouz.

Mixed reactions

Surprisingly, critic Tarek El-Shinawy, known for being pro-government, denounced the ban, describing it as “frivolity that can never be surpassed… [only after] the Censorship Authority has aggressively interfered and omitted songs [from the show]...that the Egyptian conscience voiced to challenge the oppressive power.”

“I may seek an excuse for an employee at the Censorship Authority who fears for his job and decides to play it safe…but how could the director keep silent about this nonsense. Unfortunately, ‘this is what took place,’" Shinawy wrote in an op-ed entitled “Darwish’s Whine” published in daily independent Al-Masry Al-Youm newspaper.

Khalid el-Balshy, former head of the freedoms committee at the Egyptian press syndicate, believes that “censoring these songs mirrors the general state of free speech in the country”.

“Such censorship makes officials point fingers at themselves, causing people to remember these songs rather than ignore them,” said Balshy, whose news website Darb has been blocked by the authorities.

Two months earlier, the Supreme Council for Media Regulation, an independent entity controlled by the government, made a controversial decision of allowing journalists and social media users to only report official statements about the conflict in Libya, terrorism in Sinai, the dispute over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the Covid-19 pandemic. Earlier last month, Egypt’s National Centre for Translation, a state-run entity, imposed new strict rules for translating books into Arabic, rejecting scripts that tackle controversial subjects like homosexuality and atheism.

Even though playwright El-Sayed Ibrahim wrote the musical in 2016, it was only produced this year.

“Of course, governments don’t tend to approve a performance about Sayed Darwish, as his songs represent a symbol of the [1919] revolution. But I managed to convince the [person in charge] to read the script and agree to produce it. This is considered a victory for artistic freedom,” said Ibrahim.

Ibrahim defended the Censorship Authority’s decision to censor his script.

“The Muslim Brotherhood-funded channels are taking advantage of the situation [by highlighting the ban]. We never complained about the ban; and the audience didn’t feel there was something unusual or missing,” Ibrahim argued.

“I fully support the Censorship Authority that no chance should be given to [the Muslim Brotherhood] to use our work of art in their dirty fight against the state,” he added. “The songs are available anyway online for anybody to listen to.”

Nevertheless, some in the audience begged to differ.

“How dare they remove part of our history and heritage? The musical is worthless without these songs,” one frustrated attendee said as he was leaving the theatre.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.