'Phantom force': Young Afghans fighting in Syria face uncertain future

In 2014, when the war in Syria was at one of its most bitter points, the front lines of Aleppo, Hama, Daraa, Homs, Deir Ezzor and Palmyra were suddenly filling with hundreds, then thousands, of young Afghan men.

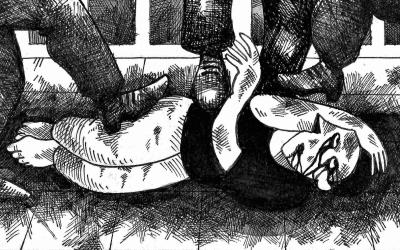

The Afghans, some as young as 14, were flown in from Iran, where they had lived as refugees. In Iran, these young men were told they were being sent to carry out their Islamic duty and protect the shrine of the granddaughter of the Prophet Muhammad in Damascus.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

After a quick visit to the shrine of Zaynab bint Ali, the men were immediately put on patrol in the capital or sent off to the front lines, where they were told they would be fighting the Islamic State (IS) group.

In reality, these young men from Afghanistan, who came to be known as the Liwa Fatemiyoun, or the Fatemiyoun Brigade, became a paramilitary force that Tehran would use to support its ally, President Bashar al-Assad.

In the years since, the graves of fallen Afghan fighters have been found in Syria and cities across Iran.

But now that Assad's place seems secure, and despite the fact that thousands of Afghans have been promised residency in Iran in exchange for their service, the Fatemiyoun has yet to be disbanded and its future remains unclear.

Phantom force

Sources speaking to Middle East Eye presented two vastly different pictures of the role the Afghan fighters, initially seen as merely cannon fodder for Iran's regional power games, currently play.

Phillip Smyth, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, says the Fatemiyoun are part of a long-term strategy by Tehran to show their ability to wield physical and political force across much of the Asian continent.

"The idea was to create a true Islamic Revolutionary Guard full of fighters from across the world, who can be deployed into any conflict in order to advance the cause of the Islamic Revolution," said Smyth.

Smyth argues that Iran wants to present the Fatemiyoun (and the Zainebiyoun, a similar brigade comprised of fighters from Pakistan) as a phantom force full of hundreds, if not thousands, of fully trained, battle-tested fighters that can present a threat to any number of countries, including neighbouring Afghanistan.

Abdul Qayoum Rahimi, the former governor of the province of Herat, which borders Iran, says that if the Islamic Republic does take that approach, it would be yet another example of Tehran and Pakistan's use of both direct and indirect forces to influence the 40-year conflict in Afghanistan.

"Iran and the United States are already at odds with each other, and if things get worse between them, Afghanistan would be the most natural battleground for them," Rahimi told MEE.

This fear was sent into overdrive in the days following the assassination by the US of Qassem Soleimani, the former leader of Iran's Quds Force, earlier this year.

'Guerilla warfare'

For years, both Iran and Pakistan have repeatedly faced accusations of aiding and abetting the Taliban, Afghanistan's largest armed opposition movement.

In 2017, police sources in the Shindand district of Herat, which also shares a border with Iran, said they found both Pakistani- and Iranian-produced arms in the district, considered one of Herat's least secure regions.

Rahimi said it was only natural for Tehran to employ young Afghans as part of their efforts in Syria.

This is due both to the ill-treatment of Afghan refugees, especially the Hazara ethnicity, in Iran, and to the decades-long conflict in Afghanistan.

"After 40 years of war, Afghans have become very adept at guerilla warfare," a fact that Rahimi said was seen by neighbouring Iran as particularly advantageous.

Smyth and Rahimi said young Afghans, who have faced decades of harassment and were relegated to largely menial labour roles, were promised not only residency but also anything from $300 to $500 a month to fight in Syria.

Both men said there is evidence to suggest that Afghan fighters have already been deployed to Yemen, Bahrain and Iraq.

No evidence

However, an Afghan security source, speaking on condition of anonymity, said such "alarmist fears" of the Fatemiyoun turning their weapons on Afghans is unfounded.

"The Afghan security bodies do keep tabs on the Fatemiyoun, but they are not seen as a credible threat to the country," he said.

The security official said some Afghan fighters remain in Syria fighting Islamic State, but that the Afghan government has seen no evidence of them being deployed anywhere else in the world.

For example, the source said that, in prior years, hundreds of Afghans had tried to enter neighbouring Lebanon to seek safety from the fighting in Syria, but were consistently turned away as suspicious foreigners by Lebanese border guards.

This statement was backed up by journalists and researchers in Lebanon, who said they had seen no evidence of Afghans being able to enter the country.

Therefore, if they had attempted to go to - or had been sent to - countries other than Iran, it would be unlikely they would have been able to enter.

Broken promises

One reason the security source sees little chance of the Fatemiyoun being used to fight in other countries, whose forces he says now number between 500 and 1,500 fighters (down from a height of up to 4,000) is that many have failed to receive the benefits they were promised by Tehran.

Agreeing with this analysis, Smyth said: "Iran isn't very good at keeping its promises... but to Tehran what matters is being 'good enough' at delivering those promises."

Smyth says Iran's economy, which has suffered under years of US-led sanctions, is one of the primary reasons why Tehran has been unable to deliver on the promised benefits.

"Part of it is just the difficulty of finding non-Iranians housing and jobs at a time when their own economy is suffering," said Smyth.

But the security source said part of the blame also lies with the Afghans, who had presented counterfeit documents, or people posing as their guardians, to Iranian recruiters.

"From the start, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps had the opportunities to verify documents and to weed out the infirm and the addicts, but they didn't because at that point they just wanted cannon fodder," the source said.

'Blooding them'

The other issue, said the security source, is the logistical challenges that the families of Afghan fighters, especially those killed in battle, face in trying to claim the benefits promised to their sons.

The source said Afghan families in Afghanistan are unlikely to arouse the suspicions of officials by advertising that their sons are in Syria.

Others, he said, have spent years waiting for Iranian visas that never materialised, despite Tehran's penchant for revering the Afghan fighters as symbols of pride.

Additionally, the security source said that the young, impressionable Afghans were never provided with a uniform basis for their benefits during the recruitment process.

Some, he said, were told that they would have to serve only one tour of duty, while others were told they would have to make several trips to Syria before they could claim their benefits.

This, said all three men, had led to a situation where the Fatemiyoun have now become an elite fighting force radicalised by their years in Syria.

"The central idea was to test these guys out, and see who rises to the top and can be used as an elite fighting force, a way of blooding them out to see which ones really advance beyond just being cannon fodder," said Smyth.

Difficult future

Rahimi, the former governor of Herat, said that in the end, though, the key to neutralising any potential threat posed by the Fatemiyoun is to end the latest war in Afghanistan, which began with the US-led invasion of 2001.

He said the peace agreement signed by the Taliban and Washington in Doha last February forbids the group from allowing another fighting force to take up residence in the country. Therefore, it is imperative that peace finally come to Afghanistan.

"If the war ends here, then it will be very difficult for Iran or Pakistan to embolden proxies in Afghanistan," said Rahimi.

Ultimately, though, Rahimi fears for the future of these young men, who have been brought up amid conflict in their home country and on the front lines of Syria.

"When you have young men who have spent five years being trained and fighting, it's very difficult for them to go back to normal daily life," said Rahimi.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.