Five books on East Africa's centuries-old connection with the Middle East

For centuries, the East African coast - extending roughly from the coastline of Djibouti all the way south to Mozambique – has been a roundabout between the Arab world, mainland Africa and the rest of the Indian Ocean.

Merchants, mariners and explorers from Arabia and the Far East harnessed the seasonal monsoon "trade" winds to sail to Africa's east coast from December to March each year. The winds reversed direction from April to September, as if designed to speed the travellers back home.

Such encounters led to the interchange of ideas, and the mingling of languages, cultures and faiths. The Swahili language, for instance, is the most widely spoken in Africa.

A Bantu language in its lexicon base, it incorporates loan words from Arabic and other tongues belonging to the merchants and colonisers who permeated the region. The etymology of the word “swahili” itself is from the Arabic word “sahil” meaning "coast".

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Literature from this region benefits from Persian, Arabian and African influences, melded to reflect the historical uniqueness and vibrant archipelago of cultures. Arabic script - known as ajami - was used to write Swahili and other African languages as early as the 11th century before the arrival of European missionaries and colonial officials introduced the Roman script.

The first known literature from the Swahili coast, Hamziya, was written in Arabic script. This was a translation of the 13th century Arabic poem, Qasida Burda, by Berber poet Muhammad ibn Said al-Busiri. The translation is believed to have been penned in the 18th century by Sayyid Idarus bin Athman, a scholar from Pate, an island off Kenya’s coast.

Most Swahili classical works, in poetry and prose, were passed down orally and for the most part remain unpublished, existing until now in manuscript form and performed in social gatherings.

The Maulid festivities that commemorate the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday is a grand event in the coastal communities of these regions. Among the prayers and supplications offered, poetry similar to the Hamziya chronicling the Prophet’s history are recited and passed on.

Contemporary works of literature by writers from the East African coast that centre characters who embody the Muslim-coastal identity are not as widely prevalent compared to those set in the interior metropolises.

Yet over the last couple of decades, there has been a revival by writers from this region who demand to be seen and have a lot to say, both critical and celebratory, of the life and experience of their communities.

The following are five contemporary novels, short stories and a poetry collection by East African authors. They each tackle current issues, including colourism, homophobia, immigration, religious fanaticism, while also reflecting the historical Eastern-Islamic fibre that binds this region.

1. The Dragonfly Sea, by Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor

The Dragonfly Sea (2019) by Kenyan author Yvonne Owuor follows the story of a protagonist named Ayaana on the island of Pate. Born out of wedlock, Ayaana and her mother Munira are looked down upon by the islanders.

Young Ayaana, searching for her biological father, waits in her mangrove hideout as the monsoon wind brings with it visitors to her small island, but never the man she yearns for.

Eventually, she "chooses" a sailor, Muhidin, as her adopted father and, once the initially elusive Muhidin begins to cherish his role as tutor and "the father who was standing in for the father who was still lost", a bond between the two develops.

But the cocoon of stability which had temporarily shrouded Ayaana is fleeting: the makeshift family crumbles as forces ranged against the island begin to mount with the rise of Islamic extremism and Kenya’s heavy-handed approach towards innocent citizens from marginalised Muslim communities to the background of the global "war on terror".

In describing a scene of brute force employed by the Kenyan government on its own people that was common in the coastal areas following the 1998 bombings in Nairobi, Owuor writes:

The fresh invaders accused and judged and roughed up even Almazi Mehdi for not answering their bizarre English questions fast enough. [They] seized market women’s baskets to search for weapons of mass destruction; who shoved fingers down the mouths of gasping fish in hopes of finding secret codes...

Owuor dips in and out of Swahili, Arabic, Mandarin and Turkish phrases with ease, often not bothering with translations - “...to savour the essence," Muhidin counsels, in one of the many life lessons he imparted to Ayaana, "you must taste at least three languages in your tongue".

And essence we taste with lush descriptions of sounds, flavours, scents and textures: from the folk music of Algerian raï to the intimacy of an oud melody; the mystic devotional music of Latif Bolat and Omar Faruk Tekbilek to Amr Diab lyrics; the taste of spiced rice and halwa to the fragrance of a mother’s rose attar; the invocations of Ayaana's poet guides, Rabi’a al-Adawiyya and Hafiz, to the spiritual delight of the island’s muezzin's call to prayer.

The book draws on a melange of cultures, traditions and histories, and explores the ocean as a carrier of memory between East Africa, the Middle East and the Far East.

Written as a delicate coming of age story but achieving much more, it becomes a critique of the West's Islamophobia, the complexity and ambiguity of youth radicalisation amid the "war on terror", as well as Kenya's treatment of marginalised Muslim communities, whose stories were born and built around the ocean.

2. Gravel Heart by Abdulrazak Gurnah

“My father did not want me" reads the first sentence from Abdulrazak Gurnah's ninth novel. Set in the Tanzanian island of Zanzibar, Gravel Heart (2017) expresses the immigrant experience and generational trauma, but is first and foremost a painful tale of a family breakdown and a strained father-son relationship.

The story is about a protagonist named Salim whose life is turned upside down when his father suddenly packs up and leaves, rents a tiny room in the back of a shop and withdraws into himself with no explanation offered from either parent that Salim can understand.

He tries to put the pieces of the puzzle together throughout his childhood and as an adult.

Salim then travels to England to study under the protection of his maternal uncle. There, the feeling of displacement and not fitting in expands and, like his father, he no longer has a sense of belonging and is plagued by a deep sadness.

Like his mother who tried to shield him from the truth of his father's estrangement, Salim in turn sends cheery letters to her, glossing over his harsh reality in England.

The theme of postcolonial intergenerational trauma is explored with the backdrop of the Zanzibar revolution of 1964 which saw the overthrow of the sultan and his Arab government by African revolutionaries. One of Salim's grandfathers was killed during the upheaval and another fled to the Emirates.

These absences had a direct impact on the fraught choices made by Salim's mother, causing the abandonment of his father which ultimately led to an adult Salim more than 4000 miles away from home feeling unmoored.

One of the most prolific writers from East Africa, UK-based Gurnah depicts the months following the revolution that are steeped in anti-Arab sentiments with a new government that was determined to "sweep away the privileged remnants of another era" by humiliating the island's Arab inhabitants.

He writes:

There was no choice but to sit silently while history was narrated anew, no choice but to wait in a dumbly unenthusiastic silence for the mocking dismantling of our old stories, until later when we could whisperingly remind each other what the plunderers had tried to steal from us. As times became harder and the humiliations and dangers mounted, the search for work and a place of safety made many people remember that they were Arabs or Indians or Iranians, and they resuscitated connections they had allowed to wither.

The term "gravel heart" comes from a line in Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, "Unfit to live or die. O, gravel heart!” used to describe a prisoner's heart of stone.

And the book is a slow and tender coming of age, tracing Salim's development from an island boy held captive by silences layered on silences, to one with a gravel heart - neither dead nor fully alive - and the bond he shares, loses and eventually recovers with his parents.

Gurnah provides a psychological character study through complicated family dynamics, national politics of post-independence Zanzibar and the diaspora experience, showing how both micro and macro level constrictions bear down on his characters.

3. The Kaffir of Karthala, by Mohamed Toihiri

Freed by the knowledge that he doesn't have long to live following a terminal cancer diagnosis, Comorian protagonist, Dr Idi Mazamba, starts a romantic affair with a French-Jewish woman as one way to break away from the social conventions and prejudices that have dogged his life and his country.

Playfully wicked as it is blatantly honest, in The Kaffir of Karthala no one is safe under Toihiri's pen. The novel is aggressive to the point of being ruthless, attacking through parodic humour all levels of Comorian society - the weak individual, the irresponsible community, and the suppressive state.

Toihiri, a diplomat who at one point also served as the permanent secretary to the United Nations for the Comoros, provides a scathing critique of European colonialism, embezzlement of public property from state coffers, the misogyny and colorism prevalent in the country and the way the precepts of Islam are flouted.

Observing the farcical behaviour of the community during Friday prayers, Mazamba writes:

Now, is there a country as undermined by corruption, as consumed by envy and jealousy, as torn by injustice, ambition and betrayal, where rascals are beatified, thieves crowned, masters of sycophancy idolized, servile smiles and laughs gratified as this archipelago? In this land, intellectual and spiritual indulgence is the guarantor of material opulence. Laanatullah alal Kaffirin!

Yet, despite the criticisms, the Comoros occupies a soft spot in the eyes of the protagonist, and indeed in Toihiri, which is evidenced when he writes about the hospitality of the Comorians: "friendly, greeted me with open arms; a natural, warm greeting with no pretence", and a country where "there is always an extra place for the unexpected visitor."

Toihiri’s second novel and the first from the Comoros to be translated into English (published in 2018 in Anis Memon's translation), Kaffir of Karthala is both a novel of social criticism and national identity. A general lack of global awareness about the Comoros and its fairly young literary scene, made Toihiri take on the role of ethnologist and sociologist by documenting the Comorian way of life.

Their language, Shikomori, a mix of Bantu, Arabic and French, is a unique dialect that leans heavily on a Swahili conservative social code: "...even the words 'tenderness', 'affection' and 'love' are non-existent in our language. We're forced to borrow them from French and Arabic. We use the word 'muhabba'. But it is shameful to say it. So, we prefer the word 'amour'."

He describes in detail their way of dressing - modestly in jubba headdresses, thawbs and keffiyehs, and how the organisation of space in the mosque for Friday prayers transforms into a hierarchy of privilege.

Toihiri skilfully plays with the word "Kaffir" in the title which could mean both "unbeliever" as referred to in the Quran, as well as a derogatory term for black Africans. In one stroke Toihiri highlights the protagonist's disenchantment with the Islam of the Comoros as well as the anti-blackness and colourism prevalent in the islands and in many parts of Africa.

In a country which values community over individualism, in which nonconformity can lead to social and psychological isolation, Idi's choice to do away with the close-knit community that is common with Swahili society, coupled with his brazenness as a black man in taking up a white mistress, was to attempt to truly embody a "kaffir" in every sense of the word.

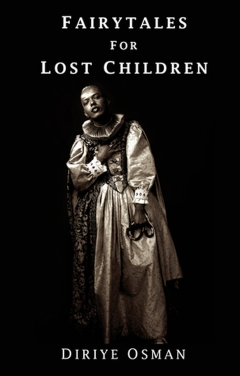

4. Fairytales for Lost Children, by Diriye Osman

Fairytales for Lost Children (2013) by 37-year-old Somali-British visual artist and writer Diriye Osman, comprises of 11 short stories which explore the intersectionality between Somali, Muslim, immigrant and queer. Some of them take place in Somalia, where Osman was born, others in Kenya, where his family fled to during the civil war in Somalia, and some in London where the family later moved to and where Osman now lives.

Coming out as queer is especially difficult for Osman's characters, who live within the traditional Somali-Muslim communities. This identity struggle is best articulated in one of the stories, The Other (Wo)Man in which the protagonist, Yassin, muses:

He didn’t belong to just one society: he was gay, Somali, Muslim, and yet all these cultural positions left him excluded. It was Somaliness, the pure beauty of being part of a proud, distinctive culture, that glued all his other selves together. He was Somali first, Muslim second, gay third

The fear of social rejection or outright physical violence is constantly present, and for some of the characters, it is a contributing factor to mental instability and collapse. Many of the stories are inspired by Osman’s own personal experiences.

One of the strongest pieces in the collection, Your Silence Will Not Protect You, appears in particular as almost an autobiographical essay about Osman's own time in hospital with a psychotic diagnosis, and about the hard break-up with the family when he came out as gay.

Osman's writing is laced with linguistic playfulness by blending Somali, Arabic, Swahili and the local patois. He also evokes the rich oral storytelling and poetic tradition that Somalia is known for.

In the first story Watering the Imagination, which sets the creative tone for the rest of the book, the narrator, who is coming to terms with her daughter’s sexuality, informs us that she tells stories to her children about "kings and warrior queens, freedom-fighters and poets” to remind her children that Somalia is a land "fertile with history and myth". Osman uses the cultural richness of Somali familial tradition to articulate the truths that are difficult to say.

The stories in the book, which won the Polari First Book Prize in 2014, are each preceded with beautiful illustrations drawn by Osman himself, which visually summarise each tale.

These images are accompanied by the Arabic translation of each title as a nod to the Quranic lessons that were a large part of his childhood in which the young Diriye was drawn to the grace and beauty of Arabic calligraphy.

5. Naming the Dawn by Abdourahman Waberi

Divided into three sections, titled in turn "Living Soul", "Seemingly No Big Deal" and "Spiritual Exercises", Abdourahman Waberi, the best-known contemporary writer from the East African nation of Djibouti, delivers a poetry collection that invites the reader to follow him on a path of awakening.

In Naming the Dawn, Waberi reminds us that "the law is not the path that leads to the source/ a century old misconception" - a plea to those who proclaim rigid and fanatic interpretations of religious texts.

Rather he asks us to let "passion for truth and beauty bound to the heart" be the tenets that guide us as we make our way through the seasons of mortal life. He reaches out with dialogue and openness to the same people who don't take time to decipher the Book of Creation because he knows "that they too have a heart /craving /closeness".

Waberi counsels us to take care of our bodies as if it were "an artist's workshop of every moment in time". He condemns indifference to suffering, "may my right hand forget me/if I turn a deaf ear to your guttural prayer" and warns us on the absence of victors in war "you cannot touch without being touched/suffering all around: rapture upon rapture/ I too am ablaze."

The final poem in this collection, which was translated by Nancy Naomi Carlson, depicts a poet who bought a wooden cage to house a paper bird. The poem is aptly titled The Hoopoe, an ode to Islamic heritage and to the early poets.

According to the Quran, the hoopoe was the reason for guidance for the people of Sheba, and according to the 12th century Sufi poem The Conference of Birds by Farid-ud-Din Attar, the hoopoe was the wisest of all birds which led 30,000 pilgrim birds on a quest for the mythical Persian bird, Simurgh.

These poems, like the fabled hoopoe, lean towards meditation and tolerance, the discovery of ancient texts and ultimately to the discovery of one's self.

In Waberi's poetry we meet fragments of the stories of the prophet, lessons from the Quran, references to classic literary stories like the star-crossed lovers "Majnun and Layla" and a tip of the hat to poets of the past to bring a collection that contains powerful historical and cultural resonances between his native Djibouti, “a country acquainted with shifting existences” and the Middle East.

Waberi stitches his words with a delicate serenity, rising up to a blend of spirituality and philosophy, which heals wounds, warms the heart, opens the soul and fills the space inside with light.

Copyright for author photos: Soeuf Elbadawi, Bernd Hartung, Dennis deCaires, Paolo Montanaro, and Steve Brown

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.