'Don't get yourselves caught': How the British state allowed its secret agents to commit crime

In the early months of 2011, as Muammar Gaddafi and the people around him fought for their lives, significant numbers of young British-Libyan men slipped into the country to take up arms against them.

Later, some of these men described their surprise at the way in which the UK’s domestic security service, MI5, had lent a helping hand, ensuring they could reach Libya and play their part in the revolution.

The following year a number of men recruited in Britain as what MI5 terms covert human intelligences sources, or “chises”, were sent to Syria, where they fought in the civil war and fed back information about their fellow fighters.

What these revolutionaries and agents and informers had in common was that they had committed serious offences under the UK’s counter-terrorism laws.

Section 1 of the Terrorism Act 2000 could not be clearer: it is a terrorist offence to use or to threaten to use serious violence; to damage property; or even to seriously disrupt any electronic system, in order “to influence the government ... of the United Kingdom or of a country other than the United Kingdom”.

If prosecuted and convicted, these men could have faced life imprisonment.

Syria is not the only country in the Middle East and North Africa to which MI5 and its overseas counterpart, MI6, have sent covert human intelligence sources.

And chises also operate in the UK. They were a critical weapon in the armoury of the British government during its 30-year struggle to quell the conflict in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles.

In an assessment published in 2016, William Matchett, a former detective with the local Special Branch – the intelligence-gathering section of the police – estimated that around 60 percent of intelligence came from informers during the Troubles, and that they saved dozens of lives each year.

Matchett also hailed chises as “force multipliers”, men and women who induced paranoia inside the underground organisations within which they were embedded. While doubtless highly useful to the British government and its security forces at the time, that effect has left a poisonous legacy: the paranoia lives on.

The Israeli criminologist Ron Dudai, who has studied the use of informers in Northern Ireland, talks of “an open wound from the past”, one that gnaws away at confidence in the forces of law and order, and which impedes the restoration of normality.

What happens, however, when the people they are spying upon ask them to become involved in a joint criminal enterprise? How can they possibly refuse, without falling under suspicion?

And of course, informers have become a half-hidden feature within some Muslim communities in Britain in recent years, recruited by MI5 and the police in an attempt to learn more about potential terrorist threats, such as those that led to five serious attacks in London and Manchester in 2017, in which 36 people were killed and hundreds injured.

Currently, some particularly productive informers in Britain “are on six-figure salaries”, according to well-placed sources – and it is difficult to see how they could be paying income tax on such under-the-counter payments.

Before they are recruited – or “authorised” - to use the agencies’ terminology, they are vetted and tested, and they must undergo reauthorisation every few weeks or months. This is a process overseen not by their handlers, but by another officer within MI5 or MI6 (or sometimes both).

Each chis is advised never to exceed the task that he or she is given. What happens, however, when the people they are spying upon ask them to become involved in a joint criminal enterprise? How can they possibly refuse, without falling under suspicion?

The benefits may be clear: permitting a chis to become involved in one crime may keep open the intelligence tap that allows many more crimes to be averted. A former head of MI5, Andrew Parker, told a parliamentary committee that chises “acquire the intelligence we would otherwise never get, that leads us to prevent really serious things happening … they give you insight that technical intelligence cannot give”.

But some of the crimes can be at the most shocking end of the spectrum: in Northern Ireland, it is now known that an agent of British military intelligence ran the IRA’s internal security unit, deciding which suspected informers were interrogated, sometimes tortured, and which recommended for execution. (The unit was known as the Nutting Squad: those who fell into its clutches were in grave danger of being dispatched with a shot to the “nut” – their head.)

Who, ultimately, decided who would live and who became dispensable while playing this deadly game? And how was such decision-making supervised?

Moreover, how can the agencies give permission to their agents to become involved in serious law-breaking, while remaining within the law themselves?

This conundrum – of how security and intelligence agencies of the British government can lawfully give the green light to unlawful conduct – is one that has been fudged for decades.

Now, an attempt is being made to deal with that conundrum through the introduction of a new law called the Covert Human Intelligence Sources (Criminal Conduct) Bill.

“This legislation”, Security Minister James Brokenshire told members of parliament, “is being introduced to keep our country safe and to ensure that our operational agencies and public authorities have access to the tools and intelligence that they need to ke”ep us safe.”

On Thursday, the bill passed its third reading in the House of Commons with MPs voting in favour by 313 votes to 98, meaning that the bill now proceeds to the House of the Lords, the upper chamber of the UK parliament, for scrutiny.

But not everybody is entirely comfortable with the way in which the circle is being squared.

The 'Aden Gang' and Northern Ireland

For much of the 20th century, MI5 and MI6 did not need to worry too much about the law, either at home, in the colonies, or abroad, as successive governments adopted a simple policy known informally in London as “disavowal” – ministers and Whitehall mandarins simply pretended that the agencies did not exist.

MI5’s powers and activities were limited only by a charter that had been issued by a government minister in 1952, the existence of which remained hidden from the British public until the 1960s.

For most of the 20th century there was no debate in parliament about the agencies’ activities or funding. Any oversight was cloistered within the executive branch of government, and the courts largely turned a blind eye to MI5 and MI6 on the grounds that they did not exist on any statutory basis.

The Cold War expedient of disavowal had become particularly important in 1948, after a new Criminal Justice Act extended the reach of English law to Crown servants in any country in which they served.

In theory, an MI6 officer arranging for the burglary of a government office in, say, Jerusalem, or planning a spot of blackmail in Damascus, was at risk of being prosecuted in London, unless it could be pretended that that officer was not a Crown servant, because he or she did not officially exist.

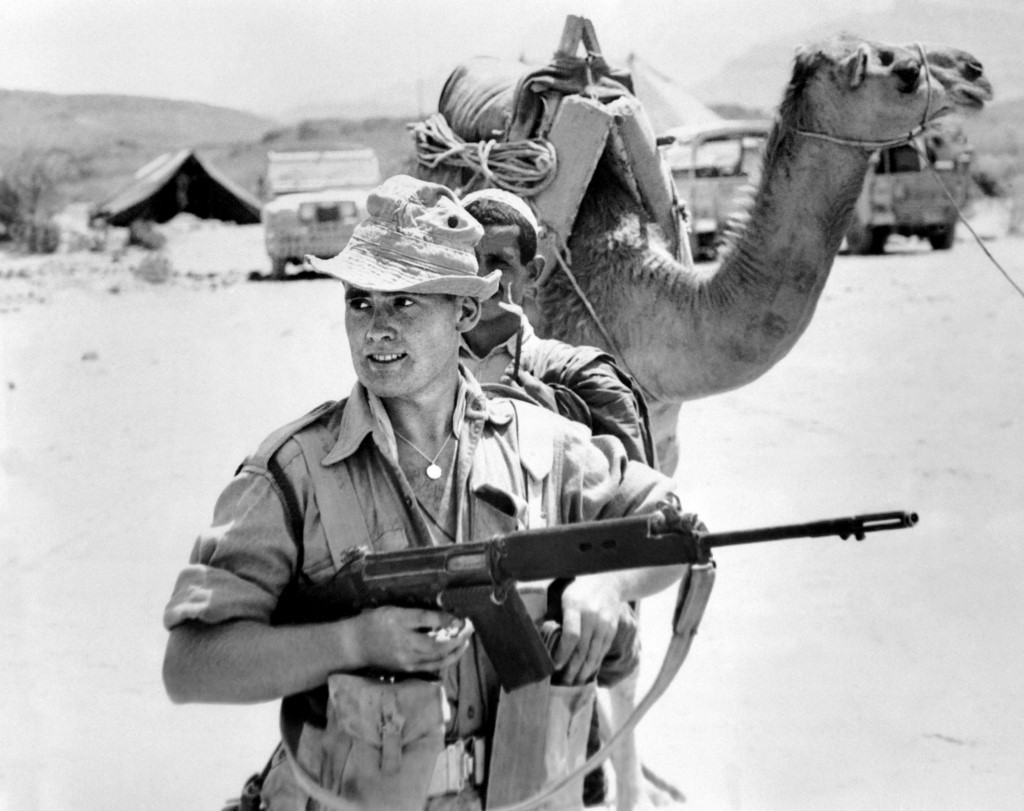

In 1969, when the Troubles began to erupt in Northern Ireland, many of the key British intelligence officers and military figures who began to appear in Belfast knew each other from Aden, from which the UK had been forced to mount a fighting retreat two years before.

They are said to have been known to each other as the Aden Gang. They were known to the public not at all, however, being officially disavowed.

In early 1976 the old Aden hands were followed by special forces, troops from the Special Air Service regiment, who arrived from Dhofar in the south of Oman, where they had played a major role in suppressing an 11-year insurrection against the sultan’s rule.

The SAS was sent to South Armagh, on the border between Northern Ireland and the republic. “I barely stopped off in Britain to see the wife and kids,” recalls one.

The regiment’s senior non-commissioned officers were instructed to draw up plans for the recruitment of agents on both sides of the Irish border. Initially, veterans of that deployment say, those plans were based loosely upon the methods they had used in Dhofar, where they had organised captured opponents into local militias known as Firqat.

By the end of the decade, a senior British army officer, Robin Evelegh, was sounding the alarm, publishing a book in which he warned that agent-running operations needed to be put on a sound legal footing.

Nothing happened. Instead, at the start of the 1980s, Patrick Walker, then a senior MI5 officer in Northern Ireland – and later head of the agency – drew up a classified report that quietly transformed the local police force from one that concentrated on solving crimes into one that gave primacy to intelligence gathering – largely through the recruitment of chises.

Throughout the remainder of the decade, as the Troubles death toll climbed to almost 3,000, senior police officers appealed repeatedly for clear legal guidance about the way in which they handled informers who had been given what was known as “participant status”.

Taking the example of an informer who reported that he had been asked to hide some ammunition, one senior detective wrote that “whatever instructions the informer’s handler give will be ‘wrong’”: if he tells the informer to hide the ammunition, both would be breaking the law; if he tells him to not do so, the informer “will automatically become the subject of suspicion (and probable eventual death)”.

In a private memorandum, government advisors concluded that “it would suit us” if any police attempt to put agent-handling on a legal basis “makes fairly slow progress”.

At this point, Raymond White, the head of Special Branch in Northern Ireland, made a direct appeal to the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher. “It was just totally unchartered territory,” he says. “We had a ten-minute conversation about that.”

Word came back that the issue was considered too difficult to handle. White was advised “to carry on what you’re doing, but don’t get yourselves caught”.

Murder in Belfast

The circle rolled on, unsquared, arriving one Sunday evening in February 1989 at the front door of the north Belfast home of Pat Finucane, a well-known and highly effective criminal defence lawyer.

Finucane was about to sit down for dinner with his wife and three children. Two masked gunmen burst through the door and and shot him six times in the head, three times in his neck and three times in his torso.

It would later transpire that the man who planned the attack was an employee of the UK Ministry of Defence and working for British military intelligence. The firearms had been supplied by a police informer, and the getaway driver, on arrest, was not prosecuted, but instead recruited as a chis.

In time, there were three separate official inquiries. They found that military intelligence, the police and MI5 had all been conspiring against Finucane.

On publication of the final inquiry’s report, the then-prime minister David Cameron admitted that there had been “frankly shocking levels of state collusion” in the murder.

Ten weeks after Finucane was shot dead, a new piece of legislation – the Security Service Act – entered the UK’s statute books. The new law was in part a response to rulings by the European courts, which had concluded that the continent’s security and intelligence services could no longer satisfactorily exist within the legal never-never land of “disavowal”, and must be placed on a statutory basis.

This law was followed five years later by a second, which similarly dragged MI6 and the UK’s signals intelligence agency, GCHQ, out of the shadows. The Intelligence Services Act set out those agencies’ responsibilities, enabling parliamentary debate and, for the first time, exposing them to the possibility of legal review in the civil courts.

The Security Service Act said nothing about authorising “participating agents”. However, as it endorsed the continuation of MI5’s core activities, the agency assumed that this authorisation was implicit in the new law.

The guidance that was subsequently issued to its officers – sometimes known as the Third Direction – remained hidden from public view for almost 30 years.

When the Third Direction accidentally emerged during court proceedings, as a consequence of some sloppy redactions of official papers, it faced immediate legal challenge. MI5 won, and the courts agreed that the agency could continue to direct its agents to take part in crime.

The case was brought by four UK human rights groups, one of them – the Pat Finucane Centre - based in Northern Ireland and named after the murdered lawyer. The NGOs are appealing against that court ruling.

The Intelligence Services Act 1994, on the other hand, is markedly less coy on the sensitive subject of criminal conduct. Section 7 of the Act sets out the way in which a senior government minister can sign warrants that “disapply” UK law, in order to shield intelligence officers from prosecution in Britain or Northern Ireland for any crime that they commission outside the UK.

At the time that the act was winding its way through parliament, some ministers believed the Section 7 measures were intended to provide cover merely for what they called “the three Bs” – bribery, burglary and blackmail.

But the lawyers who drafted the legislation, and the small number of ministers who oversaw them, could not have been clearer: the circle was to be squared completely, and any crime outside the UK was to be covered.

Kidnap and torture

In 2018, a parliamentary committee confirmed what a small number of journalists and lawyers had been reporting for the previous 13 years: that the UK government and its security and intelligence agencies had been up to their necks in kidnap and torture during the so-called war on terror.

The committee found that MI6 and MI5 had been involved in at least 670 cases in which people had been mistreated and in 53 rendition operations.

The steady drip-drip of public exposure of the agencies’ involvement in such serious human rights abuses is thought to have resulted in them seeking ever-greater numbers of Section 7 warrants.

The wording of Section 7 is dry, and not, at first glance, particularly revealing. It refers to “authorisation of acts outside the British Islands”.

But it is an evidential showcase for the way in which a modern democracy can put a clean legal face on some very dirty business.

Section 7 is - should the need ever arise - a James Bond-style licence to kill.

There were further legal refinements a few years later, with the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA), a piece of legislation of byzantine complexity.

RIPA provided a new framework for intrusive surveillance not only by MI5 and the police, but also other public bodies. It was this Act that introduced the term “covert human intelligence sources”.

While RIPA does not specifically provide for a chis to be authorised to commit a crime, one section of the Act says that any action taken by a chis following his or her authorisation “is lawful for all purposes”.

Targeting peaceful activists

A few years later, in London, it began slowly to dawn upon environmental and animal rights activists that a number of their former friends – people who had upped and disappeared from their political circles some years before – had been undercover detectives with Scotland Yard’s Special Branch.

These men had not only befriended the activists that they were spying on; they had formed intimate relationships with some, and even fathered at least three of their children.

A promised official inquiry has been long delayed, but the Yard is continuing to pay out large sums in compensation for the psychological damage that its targets suffered.

Today, any use of intrusive investigative powers in the UK is subject to scrutiny by the Investigatory Powers Commissioner, a senior judge leading a team of investigators, who reports on the application of the mass of legislation governing surveillance, and the implications of those laws for the balance between security, on the one hand, and privacy and the rule of law on the other.

Significantly, when the Third Direction came to light, it emerged that David Cameron had written in 2012 to the then-commissioner informing him that he was not to trouble himself with the question of whether or not it was lawful. His oversight “would not provide endorsement of the legality of the policy”, Cameron wrote.

When the four NGOs challenged the lawfulness of the policy, the panel of five judges hearing the case ruled that what MI5 was doing was lawful, and that the scrutiny of the Investigatory Powers Commissioner would safeguard against abuses.

But it did so by the narrowest of margins: by three to two. The two dissenting judges described the government’s position as “fanciful” and “dangerous”.

Fears over new spy Bill

As a result, the NGOs are confident that their appeal will succeed – hence the government’s attempt to quickly find a watertight way in which to lawfully authorise unlawful activities. The Covert Human Intelligence Sources Bill was drawn up, and is now being rushed through parliament.

At the first debate, a number of members of parliament expressed concern that the authorisations that give a green light to chis crimes could be employed by bodies like the UK’s Food Standards Agency, which upholds hygiene standards, and even by local councils responsible for providing basic services for a few thousand households.

Others - including former government ministers - were alarmed at the prospect of the new law giving the British government and its security and intelligence agencies the power to authorise crimes such as murder, torture or sexual violence.

'We have seen, time and again, that when the legal framework for undercover operations is ambiguous, it results in abuses'

- Maya Foa, the director of Reprieve

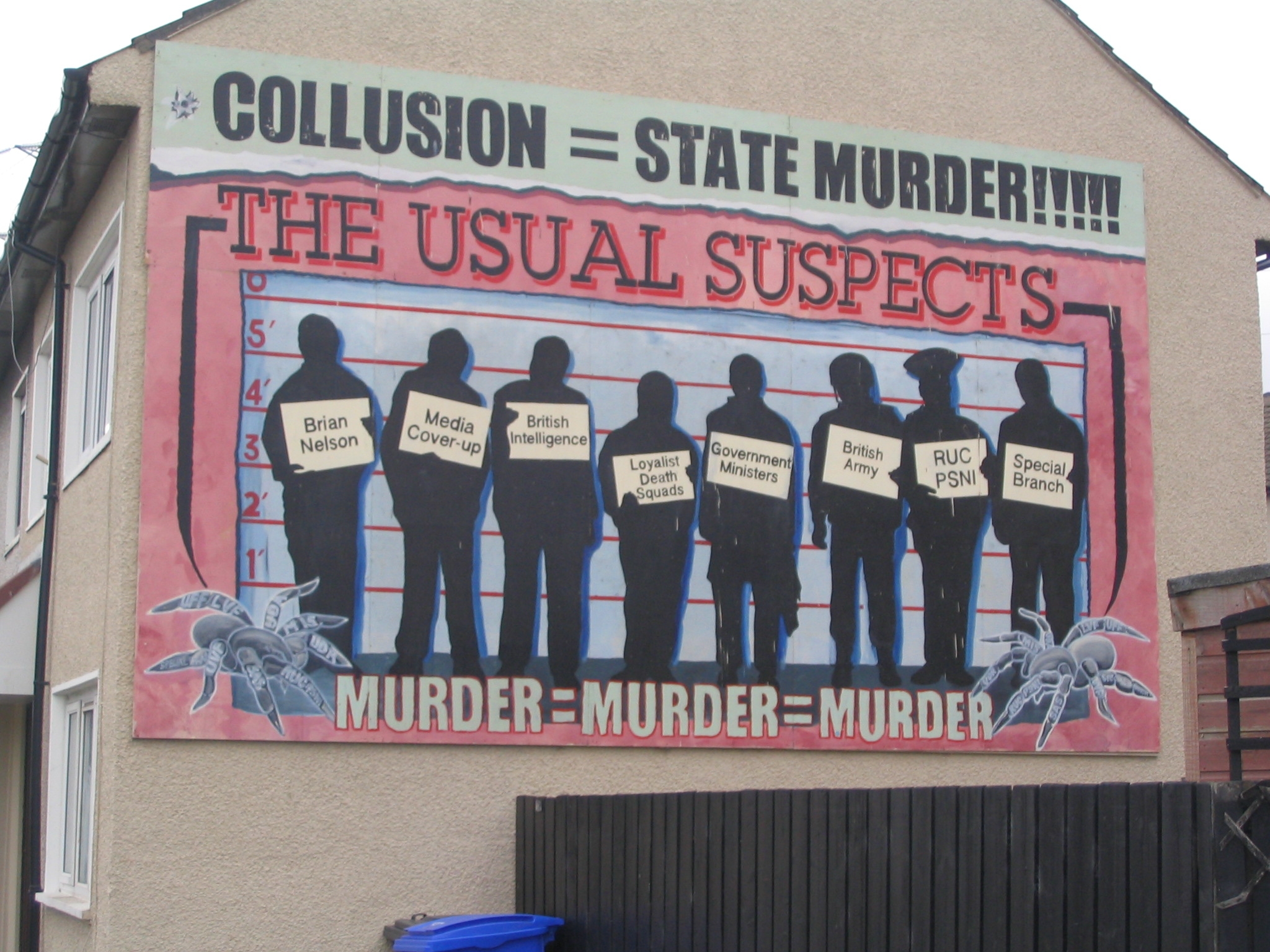

Claire Hanna, a Belfast MP, echoed Ron Dudai’s concern that the use of chises can have an unsettling long-term impact on communities.

“I speak from some experience in Northern Ireland when I say that serious crimes up to and including murder, particularly when committed by the state, are very possible,” Hanna said.

“That leads first to a generation of victims and survivors, then to deep alienation from the state and further on to the perpetuation of conflict.”

After the Bill passed its first parliamentary hurdle, Maya Foa, the director of Reprieve, another of the four NGOs that brought the challenge to the Third Direction, said there needed to be express prohibition of the most serious crimes.

“We have seen, time and again, that when the legal framework for undercover operations is ambiguous, it results in abuses,” Foa said.

“In recent years, MI5 and MI6 agents have got involved in torture and rendition and police officers have tricked women into exploitative sexual relationships, while in Northern Ireland government agents committed murders.

“To be confident that they are working within the law, police and intelligence services need clear limits, based on fundamental British values: no murder, no torture, no sexual exploitation, no secret detention.”

- Ian Cobain’s micro-history of Northern Ireland’s Troubles, Anatomy of a Killing, is published by Granta Books on 5th November

Photo: A mural in Belfast denouncing British covert collusion with loyalist paramilitaries during the Troubles (Creative Commons)

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.