How corporate tech threatens academic freedom

When Al Jazeera released its 2017 documentary The Lobby, about how the Israel lobby infiltrates British political parties and government to silence pro-Palestinian voices, followed by the 2018 leak of The Lobby USA by the Electronic Intifada, many of my academic colleagues were shocked to learn the extent of the lobby’s reach.

But for people like me, scholars who have been researching and teaching on the Palestinian struggle, the documentary films came as a painful reminder of the various methods used to attack, police, smear, silence and destroy any narrative opposing the dominant Israeli one in the US.

It reminded me of the multiple attempts by pro-Israel groups to prevent screenings of the documentary I directed alongside Andy Trimlett, 1948: Creation & Catastrophe, on US campuses and even at public venues.

But what happened during a webinar by San Francisco State University professors Rabab Abdulhadi and Tomomi Kinukawa last month took this policing and silencing to a dangerous new level.

Targeting corporations

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

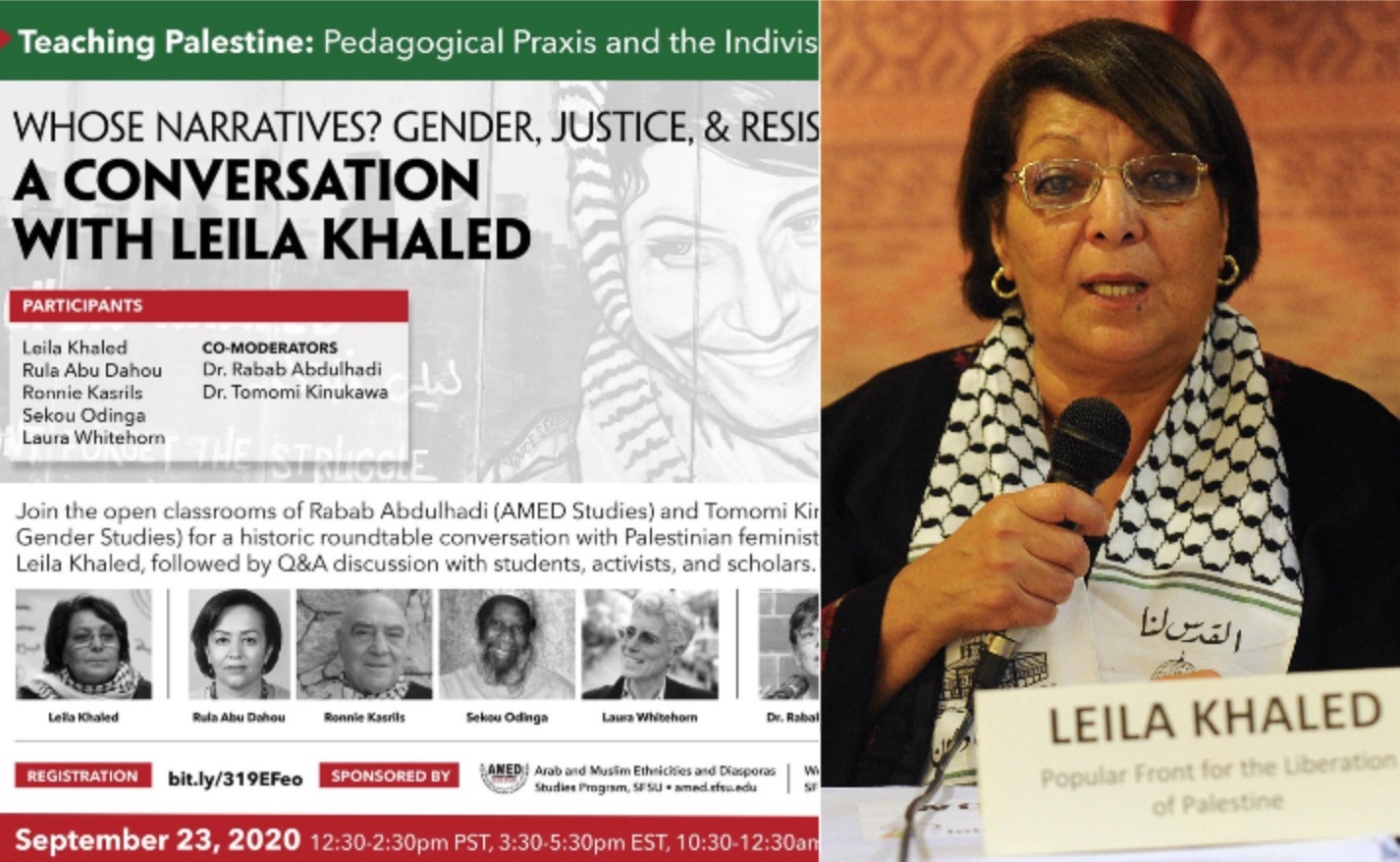

Titled “Whose Narratives? Gender, Justice and Resistance: A Conversation with Leila Khaled”, the webinar built on a months-long intellectual collaboration involving leaders of liberation movements from around the globe, including South African politician Ronnie Kasrils.

But pro-Israel groups, which include the right-wing Lawfare Project, reached out its tentacles to drive a concerted campaign to force SFSU to shut down the event, claiming it was illegal to host Khaled because of her affiliation with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and her involvement in hijacking planes half a century ago.

Zoom, Facebook and YouTube actively participated in silencing this perspective at the whim of a lobby group

The only illegal act in this case, however, would have been to infringe on the constitutionally protected academic freedom of the two professors. So the university tried to intimidate and threaten them, insinuating in an email that they could be committing a criminal activity and might face imprisonment.

The two professors and their students insisted that they were not breaking any laws, especially as there was no financial compensation involved, nor were they discussing anything outside the scope of the class.

When the university was ultimately forced to let the panel go ahead despite the lobby’s immense pressure, the lobby then targeted the corporations upon which we now depend for every aspect of our academic life: Zoom, Facebook and YouTube.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the content of the panel is irrelevant to the bigger issue of corporate thwarting of academic freedom. Zoom, Facebook and YouTube actively participated in silencing this perspective at the whim of a lobby group.

This stark, oppressive intervention not only sets a dangerous precedent for corporations to decide what is “acceptable” in a classroom, but it is also a reminder of academia’s dangerous dependence on them.

Pressure and pushback

Constitutional protections for freedom of speech, including academic freedom, were not laid down to protect popular ideas; on the contrary, the aim is to protect those ideas that are deemed unpopular and “difficult” to listen to. The neoliberal model of academia, based on the corporatisation of academic institutions, made it easy for a company like Zoom to shut down SFSU’s classroom, while the university administration did little to prevent this from happening.

The professors were left on their own to find solutions. When they resorted to Facebook to livestream the panel, Facebook took down their event page. YouTube did the same about 20 minutes into the event, just as Khaled was stating that she considered Israel a terrorist state.

In response to an inquiry by MEE, a Facebook spokesperson stated: “We’ve removed this content for violating our policy prohibiting praise, support and representation for dangerous organizations and individuals, which applies to Pages, content and Events.”

But this does not explain how the International League of Peoples’ Struggles (ILPS) was able to live stream an event with Khaled on both Zoom and Facebook about a week later. Whether or not the second event was allowed due to pressure and pushback from activists, as some have concluded, the fact remains that Zoom actively shut down a university classroom. Neither Zoom nor YouTube responded to an MEE request for comment on the matter.

This selective silencing of an academic event should be analysed first as another example of a clampdown on any serious discussion of Palestine. There have been events on US campuses, for example, where Israeli soldiers have been allowed to whitewash Israeli war crimes in Palestine without censorship.

Instilling fear

But this harassment should also be analysed in its larger context: it instilled fear in many of my colleagues who are neither activists nor have any position on Palestine - the fear of the end of academic freedom in our institutions of higher education.

We should resist this imposition and oppression and find alternatives to tech companies that monopolise the educational sphere, especially in the era of Covid-19. These alternatives should be open source, enabling us to maintain our educational mission without interference from corporations or special interest groups.

Many educators and students have been campaigning to boycott Zoom and other corporations that might control our classrooms. SFSU’s chapter of the California Faculty Association has released a resolution demanding that the university amend or cancel its agreement with Zoom.

Lastly, the US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (USACBI) called for a day of action on Friday inviting academics and student groups from campuses across North America to join their “campaign to resist corporate and university silencing of Palestinian narratives and Palestinian voices” by hosting a webinar via campuses’ Zoom accounts, including a video of Khaled.

I want to end, however, on a positive note showing that we can defy and resist. After five attempts to stop the screening of our film in West Hollywood, we ultimately ended up showing it in April 2019 to a full house.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.