Dusting off the family album: A personal history of the Middle East

Yasmine Jessy Amr was in Cyprus when she heard the news: her grandmother had suffered a brain haemorrhage and had to be rushed to the hospital for emergency surgery. By the next day, Jessy Amr had already phoned work, asked for a leave of absence, booked the first available flight to Egypt and was on her way there to be with her family.

Thankfully, her grandmother survived - but her recovery was slow. No sooner would her health improve than it would again deteriorate. The young woman did what she could to stay helpful - she cooked, she cleaned, she kept her grandmother company. But largely she spent an inordinate amount of her time pacing rooms, worrying.

To cope, Jessy Amr began an almost therapeutic practice of record-keeping and documentation: rummaging through her grandmother's photo albums became a favourite pastime, photographing the family home a close second, hoarding heirlooms and other memorabilia naturally followed.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Having grown up abroad, a stranger to her family in Egypt, Jessy Amr felt disconnected from her own culture, her own relatives. But in old, dusty photo albums, she found some solace, a refuge, that she could return to over and over again. Her grandmother got better, but Jessy Amr continued in her newly discovered hobby.

'The photographs from my grandmother's past helped me piece some of these stories together on my own'

- Yasmin Jessy Amr, contributor to the Middle East Archive

"It started as a form of meditation," she says, "feeling like an outsider, I often asked my grandmother to tell me stories about who we were as a family, who I was as a person.

"After the surgery she became forgetful, and I felt I might lose those stories. But the photographs from my grandmother's past helped me piece some of these stories together on my own."

Jessy Amr's story is one of several to be shared via the Instagram page of the Middle East Archive Project, an online platform collecting and showcasing family photographs from the region.

Each entry is accompanied by a short description, a brief narration giving the photograph's context inviting the reader to peer into someone else's life, into someone else's memory.

She had picked out the photographs for her submission from one of the old family albums she found in her grandmother's home. Among them is a black and white picture of unnamed family members, two men and two women, looking - despite being ambushed by a flock of pigeons - poised and dignified.

The description reads: "...family members I've never met. And yet in all of them I see a bit of me."

Personal history takes precedence

The archive was founded in 2019 by Dubai-based Palestinian photographer and journalist Darah Ghanem as a way of shedding new light on a region too often overshadowed by depictions of political strife, reduced to images of torn-down cities in failed states, with heart-wrenching pictures of refugees pouring westwards, driven out by tyrannical governments, foreign intrusions and ruined economies.

We have all seen those pictures and know what they mean: men and women clutching their children as they hurry across a border, families forming protective huddles in unprotected camps, fear, hunger, defeat, hatred.

The archive rejects this narrative. In its digital space, diversity and nuance are celebrated as everyday life and personal history take precedence.

"Our personal narratives are just as valid as the histories depicted in mainstream media," says Ghanem.

"They're important because they fill in the blanks between those grand moments picked up by the history books. Without personal narrative, the stories told about the region are devoid of anything human. There's no empathy after that."

And empathy is exactly what the archive gives back to the region. In one entry, submitted by Najlaa Elagelli, there's a picture of a family celebrating Eid in Tripoli, Libya: "[The] photo is taken in front of the Ghazala fountain in 1956," the caption reads, and goes on to explain how the fountain was a major landmark in the Libyan capital, built when Italian soldiers still roamed the city streets.

Seated inside the fountain is a beautiful bronze sculpture of a naked woman caressing a slender-horned gazelle, a work of art celebrating the beauty of the Orient.

But during the Arab Spring, the sculpture was torn down. There was barely any mention of it in the media. And yet here, tucked away in the archive, is a record of its mourning, of what it has meant to all Tripolitans, of what it's meant to Elagelli: "Now its empty basin has become a symbol of Tripoli and the current strife of civil war and fanatics."

And it's through this personal touch that the archive allows estranged Middle Easterners to reconnect with a region mired in conflict. Many have been driven out of their homes and may never find their way back. Yet, through the archive, they can still ruminate over a shared history, in stories reminding them they are not alone.

One of the Arab diaspora entries details the story of Souleiman Abraham, who, at the age of 19, fled the Assyrian genocide in 1915 and built a new life in Brazil, taking up the name Guilherme to better assimilate into the country and its culture. The submission was made by his great-grandson, Mubarack Marcus, a tattoo artist living in Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Marcus had come across the archive by chance, but took to it immediately as he scrolled through the entries: "There were many stories about people who were forced from their homes," he explains. "I could relate to that because my family had suffered the same way."

As far as Marcus is concerned, Middle Eastern identity is a vague, elusive thing, to be pursued and reaffirmed through practice and reaffirmation. He often infuses his art with imagery inspired by Islamic mythology, he dresses in plain colours and baggy clothes that lend themselves to no definite Western style, and he also occasionally enjoys Arabic music.

Submitting his family photographs to the archive, it seems, is yet another way for him to reaffirm his Middle Eastern identity: "The pictures in the archive show how the same history has made us," he says. "People presenting the family photos get to tell exactly how that's happened. We can share those memories and relate with each other, we're like a community."

A shared history

The shared history is there. Many of the photographs in the archive cite the same historical events that have, for so long, defined both the region and its people. Striking at the heart of all diaspora stories is the Nakba, the day that stamped Palestine a nation in exile.

In every photograph, every entry, is a family's unique experience of the Middle East, presenting their own snapshot of what it means to be Middle Eastern

The archive is full of entries about the Palestinian diaspora. One shows a family of seven siblings separated during the Nakba, reunited again for the first time in 40 years. Another shows a Palestinian couple, husband and wife, in their flower-filled garden in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where they've worked to re-establish themselves after being driven out of their home in Jerusalem.

Their granddaughter, Ayah Bazian, submitted their photograph in commemoration of Nakba Day, on 15 May. Reflecting on the picture, Bazian writes: "For me, it denotes a bittersweet moment, one as much tainted by loss as it is by relief."

Devastating as it was, the Nakba isn't the archive's grand, unifying theme. In fact, there is no single tragedy threading through all these stories and stitching them together. There's no one war or crisis that uniformly characterises what all these people have gone through. Instead, it's the geography that weaves the tapestry of history.

What brings together this whole project is the simple fact that in every photograph, every entry, is a family's unique experience of the Middle East, presenting their own snapshot of what it means to be Middle Eastern.

There's a whole generation of Middle Easterners that have grown up abroad, largely detached from the hardships their parents and grandparents have had to face. For those so-called "third-culture kids", the grand historical moments are only felt indirectly. They grew up rootless without ever having to be uprooted. They get to grapple with their history's consequences without ever having to experience it.

"A lot of us are still trying to figure out how we feel about the Middle East," says Yasmine Salam, a Londoner whose family is originally from Cairo. "Although the 20th century has defined our parents' generation, [we] third-culture kids only appreciate that history in the abstract. We know it's why we're part of the diaspora, we may be angry about it, but how much of that do we really want to absorb?"

Salam herself grew up wedged between two cultures, living in London, frequenting Cairo. She’s fluent in both English and Arabic; she’s cosmopolitan but she’s also mindful of Egyptian tradition; she majored in International Affairs at Georgetown University but wrote her dissertation on women’s representation in Egyptian cinema. By all means, Salam knew exactly where she stood, only she stood on naturally shaky grounds - always caught betwixt and between.

"The question 'where are you from' is sadly one that you're expected to really know the answer to," she explains. "I am Egyptian and do subscribe to some elements of Egyptian culture, but I'm also that hybrid who grew up in London."

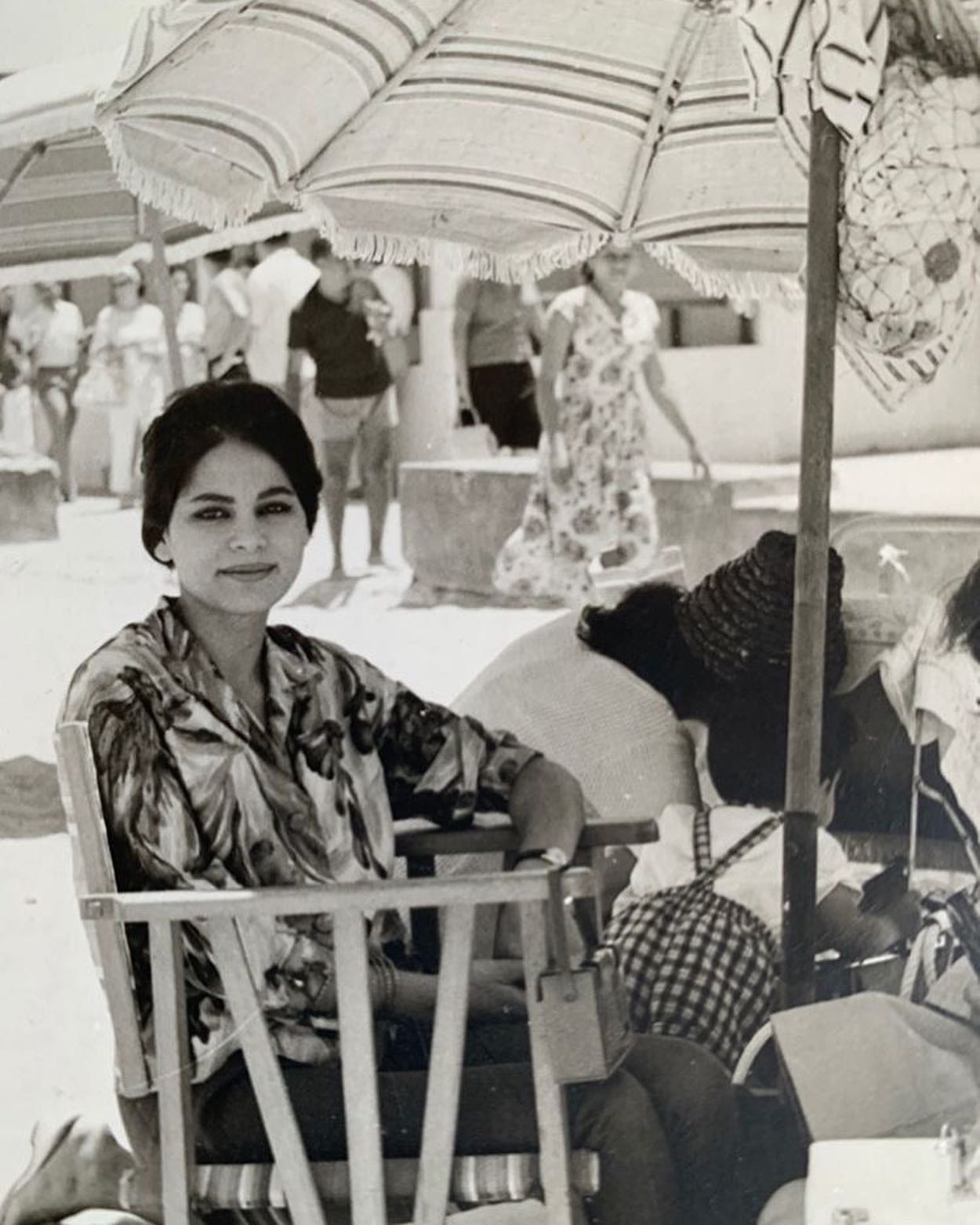

Salam's own contributions to the archive include a photograph of her grandmother, aged 17, enjoying a warm summer day at an Alexandrian beach.

The caption tells a heartwarming story of how, as a young girl, Salam sifted through her grandmother's old photo albums, begging for her to share more about their family's heritage.

Her grandmother would oblige, lovingly, flipping through the photos as she did. It's a personal memory, a humble one. There's no grand event happening in the background. Instead, the photo only tells the anecdote, reflects on it, and shares it with the rest of the archive.

What we ought to appreciate most about the archive is its communal activity: every photograph, every story, brings the Middle East to the fore, the shared narrative providing a coherent identity.

It's a collaboration among strangers, as intimate as a conversation among friends, putting the region in focus and bringing together the people whose lives have shared in its place. For those who've grown up distanced or detached from the region, the Middle East Archive gives the opportunity to close the distance and reconnect.

"The archive isn't just this beautifully curated aesthetic," Salam says. "The archive is a community that helps you remedy your relationship with the Middle East. It's a community that I want to be a part of."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.