From Argentina to Palestine, Maradona was the flawed hero of the people

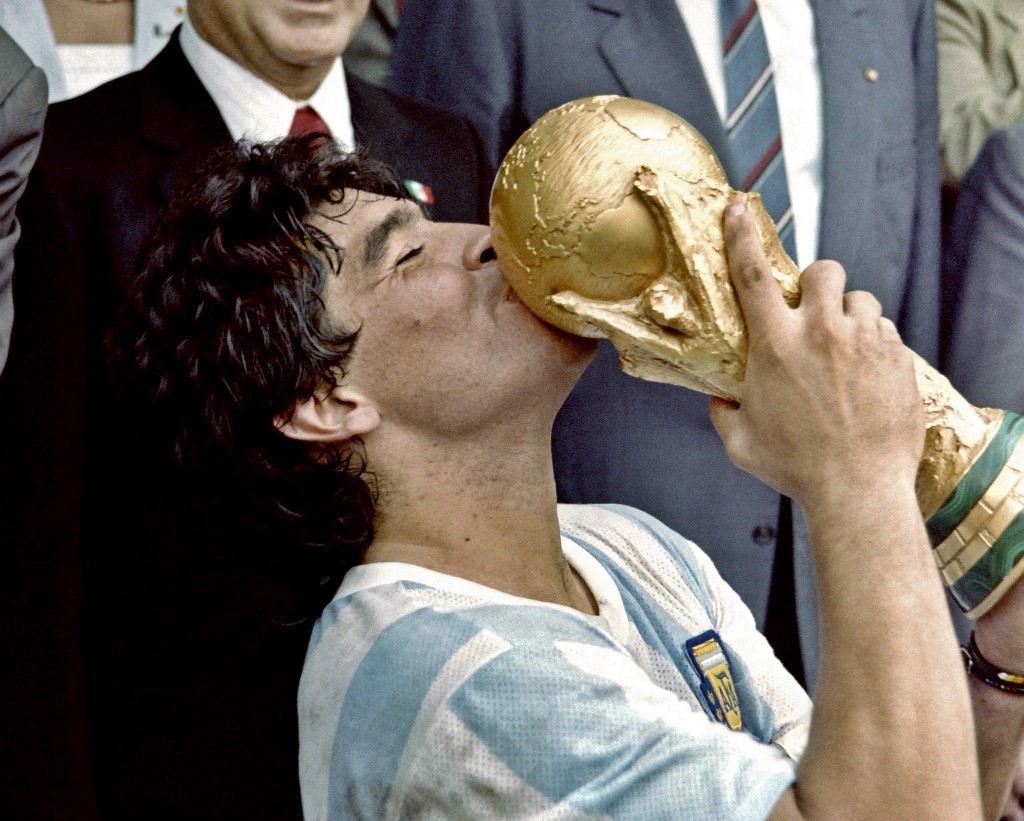

A message came from a friend in Argentina: "He’s gone." My friend isn’t a football fan but I didn’t need to ask who he was talking about. Diego Armando Maradona is dead at 60. Footballer, madman, genius, addict, icon: he was all these and more.

A boy from the villas (slums) of Buenos Aires blessed with a talent unlike any other. An imp with a mop of curly black hair, he became the embodiment of his nation and a global symbol, his image adorned on the walls of working-class neighbourhoods from his hometown to Naples, where he won league titles and became entwined with the Camorra, the local mafia.

After that first title for Napoli was won – the first in the club’s history - a banner appeared on the walls outside a Neapolitan graveyard: "You don’t know what you missed," it read.

Unfulfilled dreams

The idea of missing out was key to Maradona. You didn’t want to miss him doing something incredible on the pitch and you might not want to miss him doing or saying something outrageous off it.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Maradona contained within him the unlived lives and unfulfilled dreams of so many millions of people across the planet

But he also contained within him the unlived lives and unfulfilled dreams of so many millions of people across the planet.

One of the most beautiful tributes to Maradona captures that sense of needing to be there to see him, of a life that took in so much and that was lived by and for so many.

Para Verte Gambetear, which translates loosely as "To see you dribble" (gambetas is the mesmerising dribbling style of the pibe, or street kid), is a song by the Argentine band La Guardia Hereje. It is sung in the porteno Castillian of Buenos Aires, and tells the story of Diego in widescreen, from his childhood in the slums fooling his elders, to the hits he took at Barcelona, the triumphs and the Camorra in Naples, his political adventures and his return to Buenos Aires.

For someone who was so closely associated with the country he came from – who embodied so much of what was both great and not so great about it – Maradona was also a man and a player who belonged to the world, particularly to those people who had suffered like he had as a child.

'Hand of god'

An instructive and oft-repeated story from that childhood finds the toddler Diego falling into an open cesspit, his uncle urging his nephew to "keep your head above the shit" as he came to the rescue.

Men, women, boys and girls across the Middle East, in the dungeons of Arab democracy, could see in Maradona freedom, of movement and expression

He kept his head above that shit but also swam right through it, deep down into it. English fans will never forget the "hand of God" in 1986, but there were also crucial handballs in the UEFA Cup final of 1989 and the World Cup of 1990.

Maradona put half the cocaine in Latin America up his nose and washed it down with pizza and booze. He didn’t recognise one of his sons until that son was well and truly grown up. He admitted to drugging the Brazilian footballer Branco during a World Cup game in 1990. As manager of Argentina, he frequently told journalists to do unspeakable things to him.

There are many more of these stories, but still Maradona remained a man of the people, and something about the absurdity of so much of what he did – as well as the fact that as a boy from the slums he had had no choice but to trick and cheat his way out of where he was – endeared him to his fans even more.

He was all of life, its glory and its shame, its transcendent beauty and shabby horror. He was someone, the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish wrote in 1986, who had not blood in his veins, but “missiles”.

In that article, Darwish writes of football as “the arena of expression… in the dungeon of Arab democracy”, as a “breathing space that allows the crumbling nation to heal around a common place”. Maradona said something similar, when he described playing football as like “touching the sky with your hands”.

Men, women, boys and girls across the Middle East, in the dungeons of Arab democracy, could see in Maradona freedom, of movement and expression, an artist with a ball at his feet. The people loved him, and he loved them.

A socialist and anti-imperialist

The Argentine’s own political convictions expressed something like this. He was, in his own wayward way, a socialist and an anti-imperialist. When the Summit of the Americas came to Buenos Aires in 2005, Maradona led a counter-summit, wearing a "Stop Bush" t-shirt that denounced then US President George W Bush as a war criminal.

"In Argentina, there are people who are against Bush being there," the footballer said at the time. "I am the first. He did us a lot of harm. As far as I'm concerned, he is a murderer; he looks down on us and tramples over us. I am going to lead that march along with my daughter."

He was, too, a lifelong ally to the Palestinians. He declared the bombardment of Gaza in 2014 as “shameful”, describing himself as “the number one fan of the Palestinian people”. On meeting Mahmoud Abbas in 2018, he said that, in his heart, he was Palestinian.

He had a tattoo of Che Guevara, probably the most famous Argentine after him, on his leg. He got to proudly show this tattoo to Guevara’s comrade, Fidel Castro, who is credited with keeping Maradona alive and who, Diego said, "was like a father to me". He laughed about the "hand of God" goal on the television show of another larger than life figure who divided opinion, Venezuela’s then-president Hugo Chavez.

The politics will be argued over. When I got that message from my friend, I remembered the time I had spent in Argentina, the life I used to have, the youth I no longer have, and thought that around the world wells of memory would have been opened up by the death of this footballer. I sat my small son on my knee and played La Guardia Hereje's song to him. He watched videos of Maradona dribbling and put his finger to the screen, mesmerised.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.