Middle East cinema: The seven must-see films of 2020

The express train that is Middle Eastern cinema hit the buffers this year as the global film industry came to a halt amid the Covid-19 pandemic. The shockwaves continue to reverberate: for how long is still not known.

The year started robustly: at the Berlin International Film Festival in February, Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof won best film for There Is No Evil. But shortly after that, most film events, including festivals, were cancelled and cinemas shut their doors, halting the release of some of the region’s top titles.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A handful of Arab films – including Ayten Amin’s Souad from Egypt and Jimmy Keyrouz’s Broken Keys from Lebanon – were given the label of approval from Cannes by being included in an online line-up. But the majority of even these features are stuck in the doldrums and still awaiting a physical premiere.

By September it seemed that things were starting to improve for MENA productions. At the Venice Film Festival, the absence of Hollywood, coupled with the reluctance of many European studios and distributors to release their films, served Middle Eastern cinema well, as a record nine features from the region featured across various sections on the Lido. But the films’ qualities were an altogether different issue: conceived long before the pandemic, they largely trod familiar, if nonetheless still important, ground, including the Syrian refugee crisis, the Israeli occupation, and poverty.

To their credit, the most high-profile titles have attempted to put a new spin on their subjects, mostly through variations in genre elements, including satire in Kaouther Ben Hania’s The Man Who Sold His Skin from Tunisia; a thriller set in Palestine, 200 Meters, from Ameen Nayfeh; and magical realism in Majid Majidi’s Sun Children from Iran. The end results though left much to be desired, revealing a timidity of vision, lack of artistry and staleness of treatment.

Reinvent - or face extermination

2020 was a year when global audiences turned to cinema to feel, think and escape a debilitatingly static reality. But the small batch of Middle Eastern releases only offered more of the same: the same narratives, the same themes, the same aesthetics. Directors dared not experiment nor re-think staple topics but merely tweaked successful formulae without any deviation from the usual ingredients.

Some film-makers did produce distinctive cinematic visions. They included Tarzan Nasser’s deadpan romantic comedy Gaza Mon Amour, from Palestine, which used minimalism and a washed-out colour palette to explore midlife love and absurd bureaucracy; Khaled Abdulwahed’s refugee documentary Purple Sea, from Syria, which relied on immersive cinematography to recreate the visceral first-person experience of escaping through water; and Honey Cigar, from Algerian director Kamir Ainouz, who employed coming-of-age tropes to explore budding female sexuality, the strains of identity, and French elitism. But each film ultimately failed to expand on the limitations of their scope and flesh out their promising premises.

As festivals worldwide have struggled to fill vacant slots, so those films that were included received too much coverage from critics with little else to write about, thereby setting the bar low. In the process, the misperceived progressiveness of many features' political agenda has spawned a celebration of mediocrity. The motto “Support Middle Eastern Cinema” now rings hollow and is indicative of how friendly politics have become the pre-condition for assessing MENA films.

In 2020 the film industry and critics, including this writer, wrongly assumed that, following the success of September festivals such as Venice and San Sebastian, cinema and film-making would gradually return. We were wrong: September was only a brief respite from the perpetual pandemic nightmare. With Covid infections showing no signs of slowing down, festivals worldwide have continued to take their events online, thereby limiting the profile and scale of their lineups.

The streamers have thrown cinema a lifeline, but no one knows the world we'll wake to when normality is restored

The streamers such as Netflix, Amazon and Mubi have thrown a much-needed lifeline and will continue to control the course of cinema in the near future. Beyond that, no one has any idea what kind of world the film industry will eventually wake up to when normality is restored.

Last week’s announcement that next February’s Berlin film festival will be online means that even more Middle Eastern films will be withheld from starting their lives after lengthy delay. It will also intensify the competition for exhibition and distribution during the subsequent 18 months.

The global rollout of much-needed vaccination programmes will take time. Cinema will not now return with swing and swagger in 2021 as we erroneously anticipated. Budget cuts across Europe and the Middle East will harm production. The new realities presented to us this year will force film-makers to change direction in a way for which they are unlikely yet prepared. The rules of the game will be rewritten. The new slogan will not be “Support Middle Eastern cinema” but “Reinvent or face extermination”.

The top seven MENA films

Below I have listed in descending order my seven best Middle Eastern films of 2020. As imperfect as each undoubtedly is, they nevertheless stood out for their clear-headed engagement with their worlds in a way that transcends the Covid era, and which will keep their urgency and potency fresh long after the pandemic miasma fades.

The majority of these titles were screened to limited audiences online: the real struggle now facing Middle Eastern independent film is not only funding amid the economic meltdown, but reaching an audience in an increasingly fragmented marketplace.

7. Their Algeria

On one level, this documentary debut from French-Palestinian-Algerian director Lina Soualem, is an intimate record of the disintegrating marriage of her Algerian paternal grandparents who decide to divorce 62 years after they tied the knot in Algeria before moving to France in the late 1950s.

But on a different, more profound level, Their Algeria is also an astute study of displacement and cultural dislocation; of the millions of Algerian migrants who found themselves stranded between two worlds, neither of which they fully manage to fit in with.

The overuse of invasive close-ups and the lack of sufficient visual breaks – predictable slipups from a first-time filmmaker – bog down the flow in parts, but this still remains a gentle, affecting picture of unspoken emotions and lingering regrets and unfulfilled dreams. Most of all, Their Algeria is about the feebleness of time and the simmering wounds that never heal.

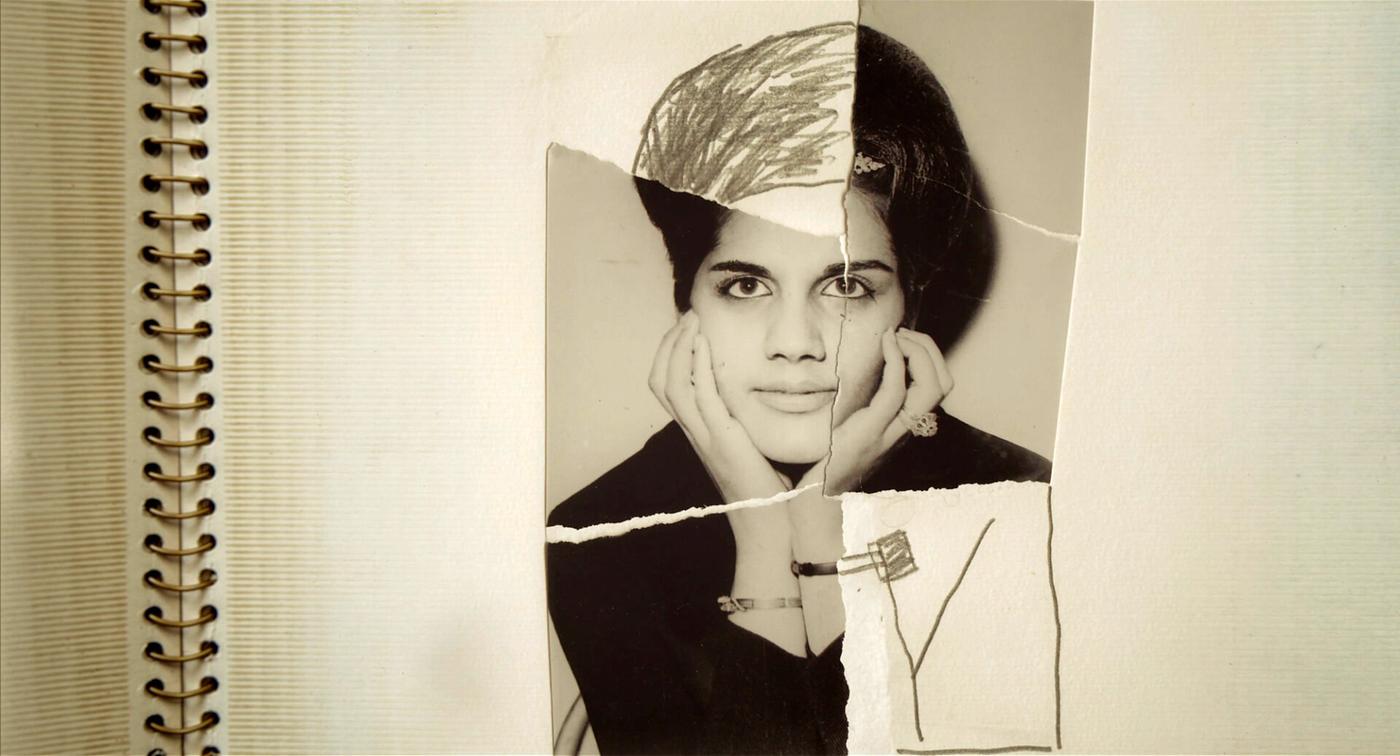

6. Radiograph of a Family

Another documentary that blends the personal with the public is Iranian Firouzeh Khosrovani’s Radiograph of a Family, winner of the best film prize at this year’s International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA).

A chronicle of her parents’ rocky marriage set against the backdrop of the 1979 Iranian revolution, this highly creative, vibrant family memoir from a sophomore director uses archival footage and home movies, letters, family photos, first-person narration and imagined off-screen dialogue to dissect the shift in power dynamics between her liberal, westernised father and her devout, religiously strict mother during the early years of their marriage in Switzerland and subsequent return to pre-revolutionary Iran.

Sober and largely detached, Khosrovani pushes the boundaries of documentary narrative, creating a work closer to docu-fiction whose main objective is to understand and analyse, if not exactly to document.

Decades of Iran’s tumultuous history are reflected in the parents’ marriage – a marriage that ultimately survives despite their acute differences. Inventive and heartfelt, Radiograph of a Family is both a piece of bravura filmmaking and a poetic essay on the endurance of love, the evolving modes of authority, and the fragility of memory.

5. I Am Afraid to Forget Your Face

I began compiling this list in 2017 but until now have yet to include a short film. That changed this year with I Am Afraid to Forget Your Face, Sameh Alaa’s critical smash which became the first Egyptian short to win Cannes’ Palme d'Or for best film in October.

Beneath all the deserved hype lies a sensitive and shrewdly political tale of a 16-year-old working-class teenager (Seif Hemeda) embarking on a dangerous quest to say one final goodbye to his deceased ex-girlfriend.

In 15 minutes and 21 shots, Alaa succeeds, in unsurpassed style, in evoking the pain, confinement and confusion of growing up in post-2013 Egypt. The meticulously-composed frames and detailed sound design brilliantly offers a glimpse of the dehumanising aural and visual noise of Cairo’s oppressive, disharmonious concrete landscape that is contrasted with the equally oppressive narrow interiors, while the sparse narrative offers a glimpse into the herculean lengths to which the depleted youth must steal for a few moments of intimacy, even in death.

Despite its short running time, I Am Afraid to Forget Your Face provides a rare portal into the mindset of a generation – one raised in the ashes of failed revolution.

4. An Unusual Summer

The new offering from Berlin-based Palestinian experimental filmmaker and visual artist, Kamal Aljafari (Port of Memory; Recollection) is his most formally daring, most elusive work to date.

During the summer of 2006, the director’s late father installed a surveillance camera overlooking the family’s parking spot in an attempt to catch whoever has been repeatedly smashing his car windows.

Ten years after his father's death, Aljafari found the abandoned low-definition videotapes. He then edited dozens of hours in which nothing seems to happen into an 80-minute film abundant with repeated gestures and daily routines. In the process he offers a glimpse of a place and a life that no longer exists.

Taking cues from leading Canadian avant-garde director Michael Snow (Wavelength) and the great French-Belgian Chantal Akerman (Down There), Aljafari constantly toys with the footage through different techniques, including inserting superimpositions, rewinding and fast-forwarding, and zooming in. Throughout, the footage is punctuated with wry, sidesplitting intertitles that flower into a full narrative in the poignant, haunting final epilogue.

Playful in its construction yet rigorous in its formalism, An Unusual Summer is a philosophical meditation on the gift of film as a vehicle that preserves time; on the power of observation; the myriad ways with which we interpret the world; and the quiet grace of the everyday.

Like nearly all of Aljafari’s work, An Unusual Summer is another piece of cinematic resistance: of the memory the occupier has recurrently ventured to wipe out.

3. Zanka Contact

Ismael El Iraki’s high-pitched, deliciously garish Moroccan debut feature is the most entertaining Middle East movie of the year.

The story centres on a stormy punk romance between a fading Moroccan rock star (Ahmed Hammoud) and a prostitute (Khansa Batma) with a stunning singing voice whom he by chance falls for after returning to his home city of Casablanca.

Borrowing from both Fatih Akin’s equally punkish Head On and Robert Rodriguez’s early Mexican action features (El Mariachi, Desperado), El Iraki shoots on 35mm, the ideal format for his dizzying array of wide vistas, scorching colours and psychedelic atmosphere. To do so he embraces every cliche of the fallen rock star playbook, using the rugged setting of a Casablanca that veers from an undeveloped metropolis to a western backdrop.

Zanka Contact is an intentionally maximalist melodrama that feverishly rushes along with contagious energy to spare, coupled with magnetic turns from its two leads. Refreshingly, it’s also one of the few successful Middle Eastern films that avoids the political themes usually mandatory for festival selection.

This is rock and roll with a big R: a big-hearted amalgam of different genres and different sensibilities that never scarifies the emotional honesty at its core for its cool cinematic flourishes.

2. There Is No Evil

The thunderous reception that met Mohammad Rasoulof’s Golden Bear winner in Berlin was offset not only by the global pandemic that derailed its release around the world, but also by the punishment handed down to the director by an Iranian court only four days later: jail for one year and a ban on film-making for three years.

Rasoulof’s eighth feature is the pinnacle of a fiercely critical oeuvre that has shifted from the allegorical (Iron Island, The White Meadows) to an overt indictment of the Islamic republic (Goodbye, Manuscripts Don't Burn, A Man of Integrity).

A four-part anthology about capital punishment – Iran is the second biggest executioner in the world behind China – that traverses different genres, There Is No Evil is his most confrontational and most directly political film to date, a treatise on the banality of evil and on the diverse and unpredictable ways with which guilt is manifested.

Although staunch in its stance against the death penalty, it is imbued by overriding ethical ambiguity. When the citizens of a self-righteous nation are forced to abide by an evil law, the choices one is forced to make are never so black and white. For many, the mere prospect of choice can be deemed an unattainable luxury; for many, the consequences of a moral action can be as damaging as following the law.

In one instance, young men undergoing compulsory military service are expected to execute fellow civilians as part of their duties. Escaping the military or refusing to follow orders are the only ways to avoid participation, which in turn will only have consequences for the soldiers and their families and fail to stop the cycle of violence.

Rasoulof does not spare any individual from blame, but he also understands how difficult it is to discern what’s ethical and what’s not when such inherent evil is normalised in the fabric of everyday life.

1. Ghosts

Much has been written about the destitute state of Turkey’s cultural scene following the July 2016 failed coup attempt, including blacklists, increasing censorship and the drying up of funds.

The fear, intimidation and lack of resources have driven the country’s independent sector – apart from a handful of exceptions – from commenting on contemporary reality. In the process, Turkish cinema has become more insular and less relevant with every passing year.

So when Ghosts (Hayaletler), Turkish director Azra Deniz Okyay’s feature debut, premiered and won at Venice Critics' Week in September, it felt like a bolt out of the blue.

Set during a single day amid a nationwide power cut, Okyay weaves a rich, complex tapestry of modern-day Istanbul anchored from the viewpoint of four characters – an aspiring dancer, a feminist activist, a shifty contractor, and the mother of a young detainee.

Istanbul is omnipresent in Turkish cinema, but seldom has Turkey's biggest city been portrayed so vividly, so thoughtfully and so accurately.

Employing a narrative that constantly jumps back and forth in time, Okyay depicts the metropolis like you’ve never seen it before: the Istanbul of the hustlers and the Syrian refugees and the drug dealers and the artists and the gays and the activists. This is the Istanbul that unsettles with its urban landscape and architectural history on the brink of extinction: a gentrified, decadent city that serves as the baby monster of Erdogan’s "New Turkey".

Okyay never attempts to hide her liberal politics: Ghosts is unabashedly secular, pro-gay and pro-immigrant, in stern opposition to the Turkish government's neoliberal policies. Yet its biggest coup is the fleeting humanity and kindness it manages to unearth amid the most inhospitable of terrains and situations.

Bristling with anger, defiance and youthful vigor, the year’s best Middle Eastern film – and one of the most striking Turkish debuts so far this century – is the shot in the arm that the country's independent cinema so thoroughly needed, and one which may carve out a new path for the struggling sector. The revolution starts here, and there’s a long way to go.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.