The power of soil: How our precarious climate shaped the Arab Spring

In 149 BC, Marcus Porcius Cato - a politician, soldier and citizen dedicated to the study of agriculture - saw a major goal realised when Rome declared war on Carthage. When arguing for this in the senate, Cato brought with him an unlikely weapon: figs homegrown on enemy territory.

The figs were a delicacy, a sign of Carthaginian prestige. Cato aimed to demonstrate that as an agricultural powerhouse, Carthage represented both a threat and an opportunity. Thanks to the quality of its soils, Carthage was becoming a trade hub and a military rival - and it therefore needed to be defeated. If victorious, Rome could use Carthaginian lands to feed its growing empire. And so the Third Punic War began, ending in 146 BC with the defeat of Carthage.

Figs decided the fate of a civilisation whose ruins now lie in modern-day Tunis. This is a reminder that what is known today as Tunisia was once a lush, productive terroir that cradled a civilisation overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, at a time when civilisational power stemmed from soil. The ability to grow in abundance was equated with security, political institutionalisation and the beginnings of trade. It was intertwined with population growth, territorial expansion and cultural standing.

Lost habitats

Like many civilisations before and after, however, Rome made the mistake of exhausting its own soils and those of its conquered territories to their ecological limits. With erosion, deforestation and intensive agriculture, soils lost their ability to harbour life, retain water and provide ecological services, such as carbon storage, productivity or temperature regulation. Entire habitats were lost in the process, and Rome eventually fell, leaving in its wake landscapes that were well on their way to extreme desertification.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Fast-forward two millennia. 2020 draws to a close amid lockdowns around the world. This year brought home a virus, along with a realisation of the dangers ahead of us due to systematic encroachment on ecosystems that normally preserve planetary, animal and human health.

I am tempted to ask where the figs of Carthage have gone, what story Tunisian soils tell us about the Arab Spring, and about the future of the Middle East in a climate-disrupted world

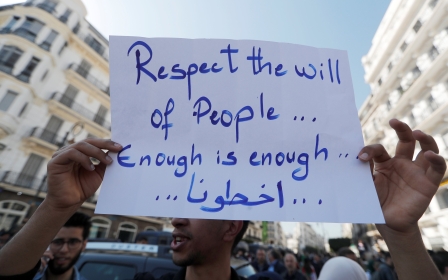

As we let go of this year, we also commemorate the Arab Spring: a series of revolutions whose fallout led to wars in Yemen, Libya and Syria, the strengthening of stifling authoritarianism in Egypt, and the arduous fight for credible democracy in Tunisia. Citizens whose dignity and agency had been stripped away descended to the streets to demand change and to overturn the concentration of political and economic power in the hands of the few who discriminated against the many.

Many analysts ask whether the Arab Spring has turned to winter, whether it has succeeded at all, and where it left the region. On the other hand, I am tempted to ask where the figs of Carthage have gone, what story Tunisian soils tell us about the Arab Spring, and about the future of the Middle East in a climate-disrupted world.

The story of the Middle East is one of continuous change, of which the Arab Spring is but one chapter. It was not an awakening - a notion that might come close to an insult in a region where encounters are charged with acute political awareness. Rather, it was a tidal wave that garnered energy accumulated over decades of growing pauperisation, corrupt governance and political abuse. The backdrop of this wave, which had been a long time in the making, was slower and quieter: ecological depletion in the Middle East and around the globe.

Struggle for survival

Mohamed Bouazizi was a street vendor in Sidi Bouzid, a governorate in central Tunisia where discrimination and bullying against those working in the informal economy remains a daily occurrence. Bouazizi was not exceptional in his daily struggles for economic survival and dignity. He was the norm, which is why he became an icon whose story resonated across the Middle East.

Bouazizi lived in an economically and ecologically stifling environment, with dusty, rocky, yellow land stretching as far as the eye can see. Where once a clement climate enabled abundant agricultural practices, there is now a desert pumped with conventional agriculture that exhausts the land from which it tries to produce. Where there was once a region fertile enough to feed the Roman empire, there is now a country that imports food and crops.

Agriculture is an economic sector that yields little, particularly for the booming Tunisian youth. But then again, neither does any other sector, apart from tourism - which offers only limited and seasonal economic opportunities - or oil extraction in the southern part of the country. Both of these sectors require the ability of workers to move from one governorate to another, an opportunity often denied by the state for security reasons.

This leaves the informal economy as the most reasonable option, even though it is dangerous, unstable and offers no social protection. In a society where social recognition and validation comes with the gendered distribution of social roles, failing to make enough of a living to provide for a family is associated with failure and humiliation.

This humiliation comes at the hands of a state that speaks the language of paternalism but fails to deliver its benefits. It is a context that generates despair, anger and revolt, visually expressed through murals of martyrs and street graffiti in the urban and peri-urban centres where most youth live. The permeating atmosphere in Sidi Bouzid today is one in which life is exhausted or disregarded. Unsurprisingly, many youth there dream of mobility and emigration as a means to dignity.

International markets

When Bouazizi set himself on fire, he was revolting against an economic system that forced dereliction upon him. This system generates wealth for an elite fully integrated into the global economy, as a result of accrued capital that they invest abroad. It is a system that lacks fundamental resilience, because the most lucrative Tunisian sectors are destined to serve international markets while national food and water security remains lacking.

In such an economy, a person’s fate is not decided just at home, but on international markets. During the weeks preceding Bouazizi’s self-immolation, torrential rains cut Canada’s wheat harvest, while drought hit Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine and China. In Argentina, a La Nina event caused crop failures for maize and soy.

With a diminished supply, prices for staple crops skyrocketed on international markets. Already at the time, Middle Eastern and North African countries imported more food per capita than any other region in the world, and the price volatility made the precarious social contracts between autocratic regimes and vulnerable populations untenable.

A black swan emerged from precarity, abuse, floods, drought and economic interdependencies. Disruptions at one end of the globe resonated with devastating consequences at another. The shock was as abrupt as the ecological depletion was profound.

In our contemporary global economic system, which considers the environment as a simple externality, ecological limits are supposedly mitigated by the ability to trade. What a country cannot produce at home, it can import, provided its economy is diversified enough to incur the costs. But in a world defined by climate disruptions and the exhaustion of ecological capacity, economic shocks and supply-chain disruptions may well become the norm. In other words, the Arab Spring may have been an appetizer for the systemic cascading of risks and shocks to which our global governance and economic systems are not fit to respond.

Water scarcity

It is no surprise that the Middle East became an early epicentre for the concentration of climate-related risks. It is among the global regions where the process of climate change started through the eroding of ecological functions. Carthaginian figs no longer exist because the soil that once produced them was systematically depleted.

Where land is exhausted, water becomes scarce and temperatures rise. With landscape change comes climate change. Add to this the rapid release of fossil energy through combustion since the start of the industrial era, and the plundering of ecosystems worldwide, and you get exponential climate change that becomes harder and harder to mitigate.

Switching away from fossil fuels to power economies is a necessary step for an effective climate transition, but it is insufficient. Regenerating the ecological functions of landscapes is the more profound and fundamental change needed to adapt to climate change and eventually stabilise the climate regime.

This change is a tall order: it entails investing massively in activities that empower populations to tend to the land and its ability to retain water. This not a one-time fix; it should be the underpinning safety net of any human civilisation.

Yet, with today’s economic models, we operate under a different logic. Agriculture must be mechanised, scaled up and monocultured in order to be lucrative. In most countries, it relies on cheap and precarious labour to generate wealth, which concentrates in minority hands. Successful agricultural models embrace international markets before embracing local, resilient production.

Beyond agriculture, we build human environments and extract energy while artificialising and depleting soils, draining water from aquifers and plundering biodiversity (where biodiversity is left). What we fail to realise is that by thinning the grounds upon which we rely, we thin our chances for survival and adaptiveness to shocks. 2010 and 2020 have that in common: They warned us of the impending consequences of our inattention to life and complexity.

Systemic resilience

So, what is systemic resilience in a world where climate disruption, shocks and the interconnectedness of risks are about to accelerate - and where regions such as the Middle East are likely to suffer dangerous consequences?

It starts with ecological integrity. This requires massive investments in landscapes that regenerate the ability of the soil to store water and carbon, thanks to which countries can fight water scarcity at the root, rather than manage manmade scarcity. This requires empowering people to regenerate and tend to their own local resources, and investing in their labour capacity and in decentralised governance systems. It requires valuing regenerative agriculture and regenerative business models as the vessels of resilience and adaptiveness in a new type of economy.

This time around, progress should mean that we aim to stop breaking ground, and to start regenerating the one under our feet

At a time when our response to climate change is to shift energy systems and to digitalise our way towards a fourth industrial revolution, we fail to recognise that our responses follow the same logic that produced the climate crisis in the first place. If we follow this path only, resilience will entail further mechanisation of human activity; an illusory decoupling of economics from the natural world; technological solutions to support business as usual, as if environmental and climatic conditions did not exist; a systematisation of responses, regardless of human and ecological cultures; and a global economy that relies on the collectivisation of risks, independent of national and local abilities to handle them, and at the expense of the public good.

This logic will hold for a while, until it generates more shocks than the system can handle at once. The room for managing disasters will become ever smaller.

The history of the Middle East, and the most recent teachings of the Arab Spring, foretell our global future: ignore ecological integrity at your peril. This time around, progress should mean that we aim to stop breaking ground, and to start regenerating the one under our feet. In other words, humanity’s future lies in reconnecting with its origins: humus.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.