Wonder Woman 1984: Hollywood can't stop its outdated take on the Middle East

Watching Wonder Woman 1984 was the most dispiriting movie experience this writer has endured during the past 12 months.

The eagerly-anticipated sequel to the 2017 mega hit that made Israeli actress Gal Gadot one of the biggest female stars in the world, it arrived on WarnerMedia’s newly launched streaming service HBO Max in the US and in some cinemas worldwide at the tail end of 2020, a year when nearly all other major franchises had been substantially delayed by the Covid pandemic, mtaking it the sole event movie of the holiday season.

Predictable, dull, highly formulaic, and strangely dehumanising, Patty Jenkins’s adaptation of the DC Comics superhero is filmmaking on autopilot: a hollow pageant that neither engages on an emotional level nor thrills with novel action.

Wonder Woman 1984 is, in other words, a standard studio flick; the equivalent of industrial chocolate whose makers employ continuous processing to produce the same exact result with every cycle.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Set in the titular Orwellian year, albeit without any connotation to the dystopian novel, the sequel sees lonely heroine Diana (Gadot) reunited with her deceased first love Steve Trevor (Chris Pine) after she casually wishes his return to a mysterious antique stone that fulfils anyone’s desires.

But the relic stone is soon stolen by down-on-his luck businessman Max Lord (Pedro Pascal), who transfers its powers to himself, spawning chaos as well as supervillain The Cheetah (Kristen Wiig).

A storm over Egypt

Shortly after WW84 - as the marketeers have labelled it - premiered, social media was bombarded with angry comments accusing it and its star, who also serves as a co-producer, of blatant racism against Arabs and of serving up a deeply dated, stereotypical depiction of Egypt.

In what feels like a forced if not downright baffling detour from the main plot, Lord flies to Egypt to meet Egyptian (or Arab?) oil baron Emir Said Bin Abydos (Amr Waked of Lucy and Ramy fame). Lord attempts to lure the Emir, dubbed the “King of Crude” by American media, into giving away his oil. In exchange, the American businessman will grant the emir’s biggest wish: the restoration of his ancestral lands and the eviction from them of “the heathens.”

Spontaneously, a giant stone wall erupts from the earth, separating the emir’s land from the rest of Egypt and depriving the poor of Cairo from access to clean water and other resources.

To add insult to injury, Gadot’s Wonder Woman is later seen in a big action sequence rescuing two Egyptian kids playing football from a speeding military truck. Commentators have expressed their anger at the sight of an openly Zionist actress, who expressed her support for the Israeli military in 2014 in a week when 16 Palestinians at a school were killed in an attack by the occupation army, rescuing two hapless Egyptian kids.

Present-day Cairo as depicted in WW84 is something you rarely see in movies: a gigantic desert wasteland populated by mute individuals draped in abayas and galabeya (save for a taxi driver who looks out of place in a light blue button-down shirt and khaki trousers). It looks even more primitive and uncivilised when compared to the shiny facades of Washington DC, where much of WW84’s narrative takes place, making Egypt look like the third world country that the filmmakers undoubtedly deem it to be.

It is also unclear who Amr Waked’s character is supposed to be. One has to go back to the period between the Muslim conquest of Egypt during the seventh century and the establishment of the Fatimid Caliphate in the 10th century to posit the faint possibility of the existence of a ruler of Bin Abydos’s profile.

History aside, what is the allegorical significance of the emir’s character? What kind of parable is this imagined division of Egypt supposed to reflect? Most importantly, who are those aforementioned “heathens”? Who, or what, are they supposed to represent?

The Cairo of the 1980s - the Cairo I grew up in - was a far more complicated place than the one glimpsed in WW84: urbane, cleaner, less densely populated, and more secular. The Cairo of Wonder Woman is the Cairo we only saw in Hollywood movies at the time and casually dismissed: the Cairo that many of my American brethren believed to be the real Cairo.

Of course, the Egypt plotline is a footnote in the WW84 story. None of these questions are answered. Superhero films are not required, nor expected, to be historically accurate. But given the fact that such a sequence could’ve taken place in any other oil-rich land, including Texas, it’s impossible not to wonder about the subtext behind the Egypt subplot – something only known to the makers of the film, including Jenkins and Gadot. One is already petrified at how they will handle Cleopatra, their next joint project, which has already been accused of whitewashing.

Critics praised the first Wonder Woman film for its feminist take on the superhero genre. But feminism does not excuse the reprehensible white saviour complex affirmed in the rescue scene.

Gadot’s involvement was bound to rouse the ire not only of Arabs, but of liberal audiences intolerant of such orientalist portrayals. But in the grand scheme of things, the Egypt debacle is not one bit surprising, or exceptional.

Hollywood's problem with the Middle East

Much ink has been spilled about Hollywood’s insulting treatment of Arabs and the Middle East over the years. The various examples are widely known, including Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Aladdin (1992), Delta Force (1986), True Lies (1994) and The Mummy (1999), as well as TV series such as 24 and Homeland.

After 9/11, the negative portrayals did not disappear, but - fuelled initially by a desire to understand what had long been deemed the exotic other, and later by mounting pressure on studios for more ethnic representation - Arab characters grew more complex, more multilayered and less caricaturish.

The real question nobody is asking is this: why does it all matter to begin with?

Examples include Kingdom of Heaven (2005), The Green Zone (2010) and Rendition (2007), to name a few. Several Middle Eastern talents have been recruited by Hollywood during the past decade, more than at other times in history, including Palestinian director Hany Abu Assad (The Mountain Between Us), Saudi filmmaker Haifaa al-Mansour (Mary Shelley) and countless performers such as Golshifteh Farahani (Paterson, Body of Lies), Hiam Abbas (Succession, The Visitor) and Ali Suliman (Lone Survivor, Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan). Netflix has started to invest in Middle Eastern content (Paranormal from Egypt, Jinn from Jordan, The Protector from Turkey) while with Ramy , Hulu has delivered America’s first TV show about Arab Muslim life in the US.

But the real question nobody is asking is this: why does all this matter to begin with?

I watched WW84 while in New York, a strange place to regard in Covid times. Currently devoid of its usual sweeping commotion and blinding street lights, America’s most densely populated city appears foreboding: a suffocating web of imposing skyscrapers and characterless apartment complexes intercepted by pockets of nature that act as small respites from the concrete maze. Seeing New York so bare, it’s difficult not to wonder how this disharmonious creation has become the most photographed and most iconic city in the history of cinema.

The New York myth is an indispensable part of the Hollywood narrative: the world’s biggest dream factory, on whose shoulders the global obsession and fascination with 20th century America was founded and fostered. During the past 100 years, the world fell in love with the US through the movies. Industries in other places during that period have been more sophisticated (France), eclectic (Germany) or authentic (Scandinavia) - but none has captivated global attention as much as Hollywood.

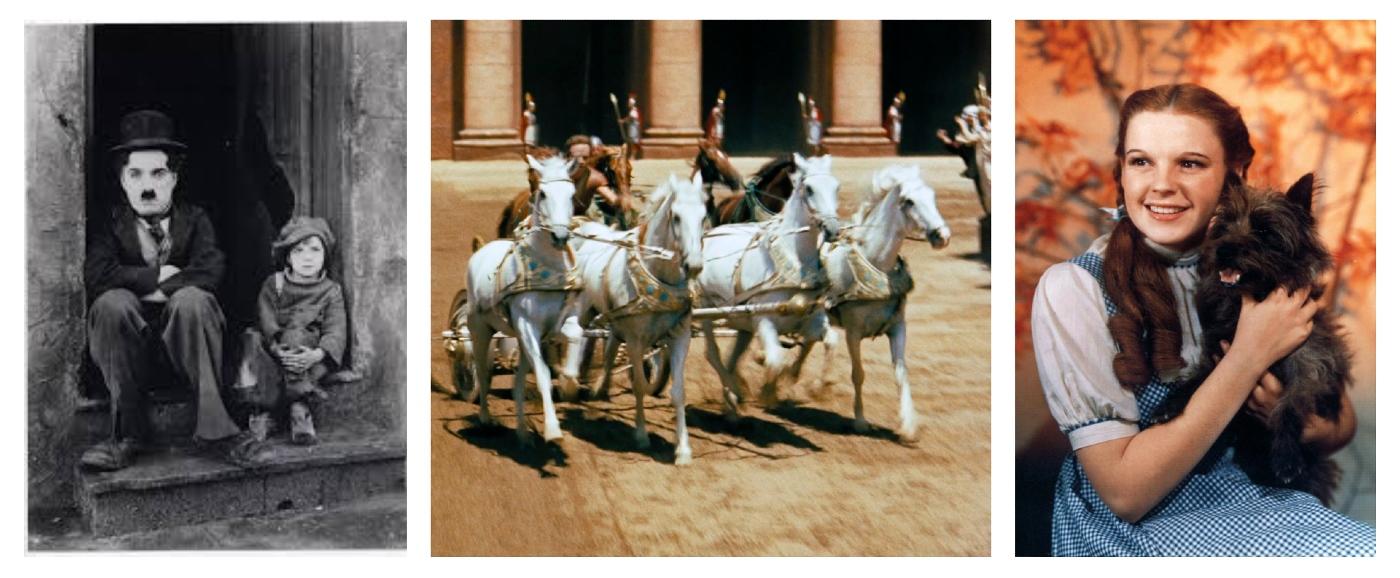

From the silent comedies of Charlie Chaplin, through MGM musicals to 20th Century Fox historical epics, Hollywood surpassed other major cinemas with its scope, ambition and trademark knack for delivering spectacles - what are now known as event films.

After World War Two, Hollywood helped cement the US empire through culture, as the biggest global superpower. Distinct from the country’s foreign policy, American studios did deliver some of the world’s most cherished visual storytelling.

But the Hollywood of yore and the Hollywood of now bear nothing in common apart from the lingering knack for the spectacle. The rise and proliferation of superhero flicks, sequels and spinoffs, notably based on Marvel Comics properties, have transformed Hollywood from a dream factory into, to quote Martin Scorsese in 2019, the manufacturer of theme parks.

The quality of the films has deteriorated but their global reach has inversely expanded thanks to the explosion of multiplexes worldwide, the rise in popularity of cable TV and the recent boom of the American streamers. Despite the rise of local streaming services and certain national cinemas - such as South Korea, as marked with Parasite’s international success; or Japan's steady supply of anime, horror and domestic dramas - Hollywood maintains its firm grip on the global cinematic industry.

For millions inside and outside the US, cinema means the Hollywood of Netflix, Marvel (owned by Disney, which also produces the Star Wars franchise and Pixar films, as well as owning the 20th Century Fox catalogue) and little else.

Even in critical circles, which now include the new breed of YouTube reviewers, Disney and Netflix productions receive far more attention than independent, non-American and arthouse films. It goes against the grain of one of the foundations of criticism: discovering and promoting new and envelope-pushing cinema.

Mainstream cinema around the world is a reductive diversion that often skirts political correctness for entertainment. Arab cinema is no stranger to this. It has vilified westerners, especially Americans and Jews, throughout its history, with its portrayals of greed, immorality and ignorance. There is also its racist treatment of Black people.

Chinese cinema’s depiction of the Japanese has never been favourable. Latin America has long struggled to faithfully represent its marginalised indigenous population. The list goes on.

Such films do not grab headlines. It is highly doubtful that the uproar which greeted WW84 would have been as intense if, for example, a medium-budgeted French comedy had depicted Egypt in similar fashion. The problem is not necessarily WW84 itself, but that it will be watched by millions of people around the world (the first film took more than $820m at cinemas worldwide, never mind download and DVD).

More than a century after the invention of cinema, Hollywood is still consolidating its power unchallenged, continuing to be the default mode of movie viewing. Not only do its productions make the biggest market shares in most countries, its recent expansion – via the traditional studios as well as behemoths such as Netflix - into the production of non-American content in both major and emerging markets will increase its monopoly over the global entertainment industry in an unprecedented way.

The danger of this monopoly, spurred especially by the streaming giants, propelled Europe’s top directors, including Pedro Almodovar, to urge the EU to regulate the operations of the likes of Netflix, Amazon, and Apple. “America understood these cultural and economic stakes when it imposed its films on other countries with the Marshall Plan after World War II,” their letter read. Today, the American conglomerates “have grown a thousand times more powerful.”

Hollywood without hope

The depiction of the Middle East in US filmmaking may continue to improve with time, but a comprehensive, authentic treatment of the region is unlikely to happen soon for two reasons: its lack of economic strength and its lack of influence in Hollywood.

Firstly, the Middle East only makes up a small portion of Hollywood’s overall global box office. Compare this to China, one of the biggest markets for Hollywood films. It is noticeable how Hollywood refrains from criticising China in any way, while altering some of its storylines to appease Chinese censors. Marvel, and by extension Disney, for example, has been consistently wary at how it handles China-related themes and issues.

In December, Monster Hunter was pulled from Chinese cinemas by distributor Sony amid allegations on social media that one of its jokes was racist. But then look at box office numbers for 2019 (those for 2020 have been heavily skewed by the pandemic). Global receipts came in at $42bn, of which the US market was the largest with $11.4bn. But China took the second biggest share with $9.1bn.

Secondly, the Middle Eastern talents recruited by the US industry show no signs of departing from the long-lasting stamp exerted by other nationalities, such as German expressionist directors like Fritz Lang and FW Murnau during the 1930s and 1940s, or the Polish and Czech talent of the late 1960s and 1970s, including Roman Polanski and Milos Foreman, thereby shaping how Hollywood sees the world.

Rather, such Middle Eastern talents have merely been employed to realise the studios’ vision - not their own. The streamers have no lofty artistic ambition. The likes of Amazon and Apple, several producers have told me, are no longer looking for serious, cutting-edge content.

It means that the majority of Hollywood films not directed by established auteurs will usually adhere to rigid formulae driven by algorithms and test screenings rather than unbridled creativity. Intentional or not, that leads to the cultural insensitivity apparent in WW84, with any subtlety lost in the shuffle amid the demand for the product to appease the tastes of the lowest common dominator.

No, America is not the world. Nor is Hollywood the creator of the world’s best cinema. And improved representation in the US industry should not be the primary objective for Middle Eastern cineastes.

But bolstering the profile of MENA cinema and producing worthwhile art and entertainment are what ultimately define the legacy of generations of filmmakers. Sadly it may be a task beyond the powers even of superheroes.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.