The horror of Srebrenica: How Quo Vadis, Aida? bears witness to genocide

There are many haunting scenes in Quo Vadis, Aida?, the awards contender directed by Jasmila Zbanic. But one lingers more than any other, despite being seemingly unobtrusive: a burning cake, left in an oven, as the Army of Republika Srpska takes over the Bosnian city of Srebrenica in the summer of 1995, part of the conflict that ripped apart south-east Europe during the 1990s.

It’s a fleeting and simple shot that elegiacally alludes to the horrors to come: the disruption of normalcy; the premature termination of young lives; and the foreboding silence of the world.

In one unassuming image, Zbanic has given us a pictogram of the lives that were, and the lives that could’ve been; of the estimated 8,000-plus Bosniak Muslim men and boys massacred during the most heinous and most notorious event of the Bosnian War.

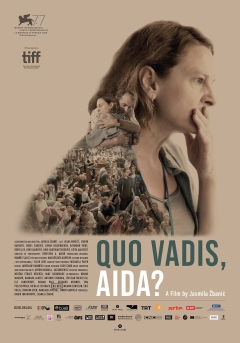

Quo Vadis, Aida? has made waves since it premiered in competition at the Venice Film Festival last September, before playing at Toronto days later. Earlier this year it won both the audience award at Rotterdam and Goteborg’s best international film prize.

The Bosnian feature has now made it to the final 15 for both the Oscars and the Bafta categories for Best International Feature Film and Film Not In The English Language respectively.

Perhaps more importantly, it will reignite discussion about the 1995 massacre, the worst case of mass murder in Europe since the Second World War.

While the primary responsibility for the atrocity lay with the Bosnian Serb army, the Dutch UN peacekeeping forces, as well as the wider UN, were condemned for failing to protect civilians in what it had declared was a safe haven under its control.

But Quo Vadis, Aida? is no mere commemoration: it’s a deeply moving, remarkably articulate plea for recognition and for honouring those lives that were lost in vain. It’s also a reminder of how apathetic the international community and global organisations can be.

The world took no action to stop the cold-blooded murder in Srebrenica just as it had during the Rwandan genocide the previous year, and as it has subsequently in Uighur areas of China, Syria and elsewhere, choosing to turn a blind eye to the engulfing injustice.

'Impotent' peacekeepers

Quo Vadis, Aida? is not the first film to tackle the massacre at Srebrenica: several documentaries have previously detailed the events, such as A Cry From The Grave (1999) and Srebrenica: Autopsy of a Massacre (2008), not to mention the misbegotten French feature Resolution 819 (2008) and the Dutch TV movie The Enclave (2002). But in contrast to these, Zbanic’s sixth feature adopts a more subdued, more resigned tone.

The film opens on 11 July 1995 - the day widely acknowledged to have been the starting date for the massacre. Aida Selmanagic (Serbian theatre thespian, Jasna Djuricic) is a teacher-turned-translator working in the Dutch-operated UN base in Srebrenica, acting as a bridge between her fellow locals and the foreign authorities.

From the get-go, Zbanic throws the audience into the middle of the pandemonium. The Serbian army, led by the subsequently convicted war criminal General Ratko Mladic (Boris Isakovic), steamrolls into Srebrenica unchallenged. The townspeople turn up at the makeshift UN HQ, begging for shelter from the looming violence but to no avail.

Mladic and his henchmen are depicted as smooth-talkers. He reassures the UN chiefs that no harm will be inflicted on the civilians, offering families soft drinks and chocolate while allowing his accompanying videographers to document the mighty destruction they have inflicted on the city.

The Serbs are the obvious villains of the story, but in their indifference and incompetence, the UN - a self-important body of diminishing significance - is no less iniquitous, as its officials attempt in vain to control the situation, copiously requesting their superiors for support.

The impotent Dutch peacekeeping force officers, meanwhile, are depicted as docile bystanders. Time and time again, Colonel Karremans (Johan Heldenbergh) demands his superiors order an air strike, but it never arrives for reasons other than bureaucracy.

In an early scene, a Bosnian community leader implores Karremans to promptly act before warning him that he shall be held accountable, only to be casually dismissed. “I’m just a piano player,” the Dutch commander tells him.

Amid the raging frenzy, the maternal, calm Aida struggles to keep her composure, shuffling between escorting as many people as possible to safety while also exploiting her position to have her husband and two sons admitted to the UN camp.

Aida is noble and graceful, but, like all people, she’s no saint. She never questions her choices, never shows remorse for using her newfound status to protect her family. In war, there are no heroes. Aida is simply human.

Helpless and abandoned by the world, the Bosnian men who are being driven to their deaths in buses show little resistance, knowing there’s almost no way out.

The steady build-up of the escalating tension climaxes with a glimpse of the massacre that saw more than 8,000 men shot by Mladic’s army during 10 days.

Nearly every scene prepares the audience for the carnage to come, and yet the cruelty and callousness of the incident itself ultimately proves to be insufferably devastating, through the cold, clinical, detached fashion in which Zbanic depicts it.

Bypassing Muslim identity

Zbanic came to prominence when her first feature, Grbavica: The Land of My Dreams, a devastating, sensitive account of the aftermath of the rape of Bosnian women by Serbian soldiers during the war, earned the Berlin Film Festival’s Golden Bear award for best film in 2006.

She has strived to replicate the vigour and power of Grbavica in her subsequent work to middling results. For Those Who Can Tell No Tales (2013), an account of the war site turned tourist resort of Visegrad, was hampered by its white Australian perspective, which restricts its scope and impact, while the apolitical Love Island (2014), a misfiring romantic comedy, was short on laughter and laden with clichés.

More intriguing was On the Path (2010), a contemporary domestic drama charting the disintegrating relationship between a secular air hostess and a former alcoholic soldier who gradually converts to a more conservative form of Islam. It is also Zbanic’s only feature to tackle the growing role political Islam has played since the war and its impact on the Bosnian identity.

Intriguingly, Islam and Muslim identity is deliberately bypassed in Quo Vadis, Aida?: none of the characters identify themselves as Muslims, even in the brief epilogue set after the end of the war. The Serbian military chiefs also seldom refer to the Bosnians as Muslims.

In one notable scene, Aida encounters one of her former students who has joined the Serbian army. The young soldier nonchalantly asks her about her son, a friend of his in the former Yugoslavia, before he coolly departs to the death buses. This brief, if highly symbolic, scene is a reminder that the Bosnian war was not religious as it was later framed to be but strictly ethnic, even territorial.

'Clear-eyed' humanism

All of Zbanic’s films are defined by unshowy aesthetics. Her stories are classically told for the most part, both narratively and visually, with imagery in the service of the narrative. It’s a self-effacing approach that no longer sits well with the jaded critics and programmers, which explains the lack of anticipation in Venice prior to the film’s premiere and the consequent surprise when the movie was found out to be masterful. Being bombarded with a glut of indistinguishable images and narratives, many now gravitate towards more aesthetically adventurous works and genre-bending fares.

Her straightforward filmmaking can indeed feel humdrum and unexciting when the narratives are not tightly conceived. Yet what distinguishes all of Zbanic’s cinema is its quiet grace and its clear-eyed humanism; its ethereal poeticism and its belief in the possibility of deliverance. And her approach is apposite for an atrocity such as this.

The question of form, or more accurately how tragedy is presented, always arises when tackling a real-life subject of Srebrenica’s weight and magnitude. Moral questions about what the film-maker shows and how they approach this are an indispensable facet of such a conversation between film-maker and audience, as well as critics and scholars, who are part of the audience naturally.

An ostentatious or exploitative approach for the sake of entertainment brings attention to the film-making itself instead of the subject at hand.

Zbanic eschews these pitfalls by keeping her story grounded in the reality of what happened without embellishment. The narrative is structured as a tense non-generic thriller of sorts but the only tension comes from the inevitability of the bloodshed to come. There’s nothing remotely sensationalist in Zbanic’s method, nothing titillating.

When watching a war movie, one often wonders what relevancy could it possibly have. In the case of Bosnia, the scars are still burning. The collective trauma is yet to heal.

And just as the innocent populace found themselves victims due to their ethnicity, so Bosnians - still identified by their Muslim religion - continue to be shunned by Europe, much of which is still to recognise Srebrenica for what it was.

Quo Vadis, Aida? is neither a documentation of Srebrenica nor is it an interpretation of the events.

Instead it stands as a faithful dramatisation, whose main purpose is to demonstrate the grave loss incurred by the war.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.