How Israeli rights groups prevent Palestinians from framing their own reality

In recent years, people of colour working in the human rights and international development sector have called on NGOs and agencies to examine institutional racism, and to look at how their structures, discourses and programmes reinforce colonialism and white supremacy.

Last year, 1,000 former and current staff of Doctors Without Borders called for an independent investigation to dismantle “decades of power and paternalism”. A year earlier, a report by an independent commission determined that Oxfam International was plagued by “racism, colonial behaviour and bullying behaviours”.

But this emerging global conversation appears to have skipped over Israeli human rights organisations, still praised for their courageous fight against Israel’s occupation and their advocacy of Palestinian rights. The recent report from B’Tselem, which declared Israel to be an apartheid state, offers an opportunity to speak about the racial politics of Israeli human rights work.

Racial hierarchy

Some Israeli rights organisations are not only imbued in the settler-colonial system and benefit from it, but they also embody and reproduce in their institutional structures and operations, racial colonial power relations. Put more bluntly, the Israeli human rights sector has an Ashkenazi Jewish-Israeli supremacy problem.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A close look at the staffing structures of such organisations reveals a striking picture of racial hierarchy between Israeli Jews, ’48 Palestinians (also referred to as Palestinian “citizens” of Israel), and Palestinians from the occupied West Bank and Gaza (also referred to as ’67 Palestinians) - the same hierarchy upon which the Israeli racial settler-colonial project rests.

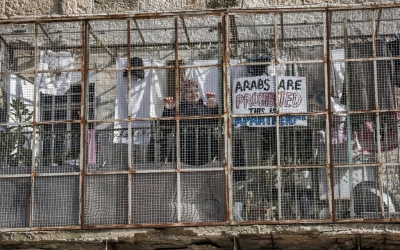

Palestinians are designated specific roles... yet, even though they are the backbone of these organisations, they are barred from top-level positions

Palestinians from Gaza and the occupied West Bank have two main roles in Israeli human rights organisations. They are the field researchers tasked with documenting violations of human rights, collecting data and taking testimonies. They are also the “clients” and “beneficiaries” who appeal to these organisations to help them secure their health, education, residence and movement rights vis-a-vis Israeli authorities.

Then there are the ’48 Palestinians, who occupy positions that demand a good command of both Arabic and Hebrew. Their role is to mediate between ’67 Palestinians and Israeli staff. They are the data and intake coordinators who manage fieldworkers, process information and coordinate the programmes that require direct communication with ’67 Palestinians.

Finally, positions such as chief executives, spokespersons, international advocacy coordinators, resource development staff, and researchers who write public policy reports - the public faces of the organisations - are Israeli and Jewish American, almost exclusively Ashkenazi.

Colonial fragmentation

This is by no means a critique of Palestinian staff and their agency within Israeli human rights groups. Palestinian activists have long negotiated questions of livelihood and resistance while living under colonial conditions.

As in Israel’s racialised labour market, Israeli human rights organisations have their own glass ceiling. Palestinians are designated specific roles, without which the Israeli Jewish human rights groups cannot operate - yet, even though they are the backbone of these organisations, they are barred from top-level positions, which are mostly reserved for Ashkenazi Jews.

The division between the labour of ’48 and ’67 Palestinians also plays into and deepens the colonial fragmentation of Palestinians. It risks triggering internal power dynamics and a hierarchy between ’48 Palestinians, who serve as mediators, and ’67 Palestinians, who seek assistance or share their testimonies.

The deep-seated racism - and racism does not have to be conscious or intentional - that underpins this staffing culture also underscores questions of knowledge production and representation. In these organisations, Palestinians and their experiences of settler-colonial violence are instrumental for Israeli knowledge production. They are the source of information, and their lived experiences are the raw dataset.

It is the Israelis who decide what to do with this information, how to interpret and frame it, and how to communicate it to the world.

Arbiters of Palestinian agency

In a 2016 interview, B’Tselem’s executive director, Hagai El-Ad, was asked: “How do you give Palestinians voice and agency in your work?” His reply was telling:

“That’s a very important question, which we think about all of the time. One of the main ways is through our video project, which is a leading global example for self-empowered citizen journalism. Palestinian volunteers, more than 200 of them all over the West Bank, have video cameras, and are empowered to document life under the occupation. Of course, the footage later released is the original footage the way it was shot by Palestinians.”

The question, in itself, displays some of the harm these human rights organisations do by playing the role of mediators of the Palestinian experience - the givers of agency and voice. By assuming the authority to shape international perspectives of Palestinians, they act as the arbiters of Palestinian agency.

At the same time, El-Ad’s answer suggests that the most the natives can do is document their reality. The Israeli human rights sector appears incapable of envisioning Palestinians as knowledge producers, or framers of their lived reality. The empowerment of which El-Ad speaks is a classic case of liberal empowerment devoid of power - one that sits well with the white saviour mindset.

An important aspect of this exploitative, racialised relationship is the emotional and psychological labour expended by Palestinians in collecting the information and testimonies necessary for the existence of these organisations.

While Palestinians are tasked with documenting and processing the horrifying settler-colonial violence to which they are subjected, Israeli staff receive processed and “clean” information to use in their reports, international advocacy work and public campaigns.

Cycle of violence

While this dynamic traps Palestinians in a cycle of violence that leaves them emotionally and politically exhausted and (re)traumatised, it shields the occupier from any direct involvement. Israeli staff receive the testimonies filtered and mediated, adding a further layer of disconnect between the occupier and the consequences of the occupation and colonial violence.

The racist structure that puts Palestinians in the back seat in these organisations also informs the politics of representation, which views Israelis as the natural representers and framers of Palestinians’ lived reality. This is joined by a sense of self-righteousness. In an interview with the New Yorker, El-Ad explained why B’Tselem decided to call Israel an apartheid state: “We want to change the discourse on what is happening between the river and the sea. The discourse has been untethered from reality, and this undermines the possibility of change.”

Our lived realities and knowledge should not be footnotes in the reports of white, Israeli, settler-colonial organisations

What B’Tselem and El-Ad ignore is that their own discourse has been untethered from reality. Had they listened to Palestinians, they would know that Palestinians have been saying for decades that they live a reality of apartheid, racial segregation and racial domination. This erasure is the result of a condescending approach that insists the settler knows better than the native.

Yet, within the racialised international scene, Palestinian activists, lawyers and human rights groups - such as Al-Haq, Al Mezan, Adalah or Addameer - do not receive the same international attention as B’Tselem or Israeli lawyer Michael Sfard of Yesh Din, with dozens of interviews and coverage in leading international outlets, and access to decision-makers.

Centring Palestinians

Israeli human rights organisations, activists and lawyers do not merely “use their privilege” to “help” Palestinians - a claim white people often make when they centre themselves. They speak of apartheid, but they do not work to undermine the politics that privilege them. Instead, they capitalise on and benefit from the politics that render Israeli voices as more valuable and legitimate - and they do so while exploiting Palestinian knowledge and labour.

This racial dynamic also influences the types of knowledge and discourse that are produced. Israeli human rights organisations assume the authoritative voice on Palestinian issues internationally. B’Tselem is now the go-to group on Israeli apartheid, Gisha on Gaza, Yesh Din on Israeli settlements in the West Bank, Physicians for Human Rights on health, and HaMoked on questions of status.

The result is a settler reading of the Palestinian experience. With the insistence of Israelis to define the Palestine question, the framing they offer and the knowledge they produce tends to undercut Palestinians and the radical anti-colonial agenda that centres liberation.

For example, while Palestinian radical politics sees in Israel an apartheid settler-colonial state and argues that Zionism is racism, B’Tselem advances an understanding of Israeli apartheid that ignores settler-colonialism and denies the racial underpinnings of the Zionist movement.

Palestinians know how to frame their own reality; they have been doing so for decades. Our concern is less with how to make Israeli organisations and activists less racist or more accommodating of Palestinians. We are more concerned with how we, as Palestinian activists, human rights organisations and solidarity groups, should respond to this racial dynamic.

Our lived realities and knowledge should not be footnotes in the reports of white, Israeli, settler-colonial organisations. A way forward is to centre Palestinian knowledge and the liberationist anti-colonial agenda.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.