Midnight Ramadan League faces backlash over links to counter-extremism programme

A player and an advertising agency involved in a high-profile Ramadan football tournament in Birmingham have told Middle East Eye that they were not aware of the project's links to a controversial UK government counter-extremism programme.

Last week, MEE revealed that the Midnight Ramadan League, which currently features in an award-winning advert for EA Sports' FIFA 21 video game, was created with the involvement of strategic communications firms involved in shaping covert campaigns for the Home Office.

The revelations have prompted fresh questions about the use of so-called "astroturfing" - organised and deceptive government-backed activity that falsely creates the impression of a spontaneous grassroots campaign - targeted at British Muslims in order to "effect behavioural and attitudinal change".

A football coach who played in the league, which concludes this weekend, told MEE he felt "duped" by the initiative, and that it was "unfair" that participants were not made aware of the organisations backing it.

He said he was not informed about the project's link to the Home Office and might have thought twice about playing in the tournament if he had known beforehand.

"This is first time I'm hearing that the league is part of the [counter-extremism] campaign," he said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

"It's no surprise that it's been kept low profile because it may not have garnered the support from the community that it has had it been clear. It makes me feel a little duped as a participant and uncomfortable with the intentions behind the campaign. Would I have participated if I'd had the full information? Maybe not."

The amateur footballer said it was "unfair" that the Midnight Ramadan League could "hide" its support from the counter-extremism programme.

"Transparency is key to community cohesion, and it's the responsibility of organisations to make clear who's supporting such projects," he said. "Muslims are already at a disadvantage in society currently, so trust has to be at an all-time high for us to thrive."

Government support

Obayed Hussain, the organiser of the league, told MEE that the project received government support "to help publicise our services". He said the league was sponsored by EA Sports and local businesses.

"We're really proud of the work we do. I've spoken to players and supporters about the support we receive, and right now everyone is looking forward to the league finals and Eid this weekend," he said.

But others in Birmingham told MEE they were concerned to learn of the league's links to the Home Office counter-extremism programme.

Yusuf Ali, a Birmingham resident who frequently plays football in the local area, said it was "upsetting" that grassroots sport was being used in connection with counter-extremism.

"It's very disappointing, especially for someone like me, who loves watching and playing football," he told MEE. "I think the disappointing part is that, have we really moved past this rhetoric where we're being condescended [to]? They're saying we're so at risk of being on the outskirts of society that we have to try and integrate back into British culture by [participating in] this league."

'Real Muslim culture'

The Midnight Ramadan League had received widespread praise from Muslims and football fans after it was promoted in a FIFA 21 advert encouraging British Asians to get involved in sport.

The advert, which also features Leicester City's Hamza Choudhury, one of only a handful of British Asians to have played in the Premier League, was hailed in industry magazine Campaign as "representing real British Muslim Ramadan culture" and moving away from "stereotypical Middle Eastern or Indian cultural depictions".

The campaign was launched after EA Sports and advertising agency adam&eveDDB last year won a Channel 4 Diversity in Advertising award in response to the broadcaster's invitation for pitches "focused on the authentic representation of UK Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic cultures within TV advertising".

But a spokesperson for adam&eveDDB told MEE: "We weren't aware of any such connection, with our only partners on this campaign being FIFA and the production companies we worked with to create the film."

EA Sports declined to comment. MEE also contacted Channel 4 and sought to reach Hamza Choudhury via Leicester City and his representatives, but none responded to requests for comment.

The Home Office has been involved in other football projects targeted at British Asian communities.

Altus Football, which ran in 2018 and 2019, was a programme that offered free training and mentoring for 16- to 18-year-olds in East London, Birmingham, Bradford and Derby. It received Home Office support, according to its website's privacy policy.

Ali, 23, told MEE it looked as though the Midnight Ramadan League had been introduced to reduce the risk of local Muslims "doing something stupid," and questioned whether other minority communities would be targeted in the same way.

"The kind of people who play football are not the ones at risk of extremism," he added.

"The craziest thing about it is that it is bringing politics and agendas into such a simple game and it's just disrespectful and quite upsetting."

'Securitisation in action'

Academics and Muslim activists also raised concerns about links between projects such as the Midnight Ramadan League and the government counter-extremism programme, accusing the government of "securitising" Muslim daily life.

Rizwaan Sabir, an assisstant professor in criminology at Liverpool John Moores University, told MEE: "Initiatives such as this are about diverting and disrupting those classified as potential future terrorists.

"Built into this idea is the deeply divisive and offensive assumption that Muslims are somehow inherently dangerous and therefore need some sort of pre-emptive state intervention to stop them from becoming violent some day in the future."

Sabir said that the "secretive" and "underhanded" methods were particularly harmful, and demonstrated a "culture of impunity that is inherently undemocratic".

"Secrecy breeds mistrust, anxiety, and uncertainty and can lead to deeply damaging psychological and physiological effects on individuals and entire communities."

The academic noted that such campaigns led to stigmatisation and criminalisation because they particularly targeted Muslim men aged between 18-35, "who are viewed to be most susceptible to becoming future terrorists".

Home Office rejects FOI request

MEE sought details from the Home Office about its support for the Midnight Ramadan League via a Freedom of Information (FOI) request. This was rejected in a response from the Office for Security and Counter-Terrorism on national security grounds.

"The fact that the state is using 'national security' exemptions to prevent the release of information on this project raises serious doubts around the innocence of this project," Sabir said.

Yahya Birt, research director at London-based think tank the Ayaan Institute, told MEE that government support linked to counter-extremism and counter-terrorism policy for projects such as the Midnight Ramadan League was an "insult" to the Muslim community.

He said that such campaigns should be openly supported by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, and not the Home Office.

"Support it because it's important for Muslims to get together and play sports during Ramadan. Not because you fear that if they don't play football they might become radicalised," Birt said. "That's an insult."

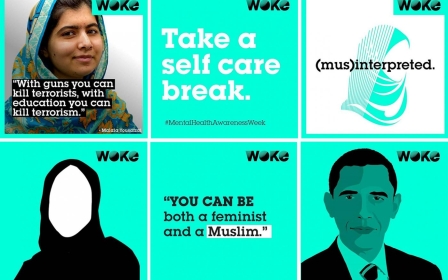

Birt has previously written about how astroturfing has negatively impacted the British Muslim community, citing as an example "This Is Woke," a progressive social media network that MEE revealed was a covert British counter-terrorism programme.

The researcher said there needed to be a critical discussion about the cost and impact of the state "securitising" Muslims participating in every-day civil society activities such as playing football.

Birt played down the distinction between direct funding and other methods of state backing, asserting that assistance from the government's counter-extremism campaign for seemingly grassroots initiatives came in many forms.

He said this included support through "patronage, in-kind services and training," which were "often channelled through proxies... to give it a palatable front".

"The people who run the project can be proud of the league itself, but there is a cost to this securitisation taking over Muslim life in this country," he said. "We must resist that, we must have more worth for what we do."

“Three million Muslims in the UK make a fantastic contribution, we are not just a community at risk of political violence. The state has to see us as full citizens and not just suspects.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.