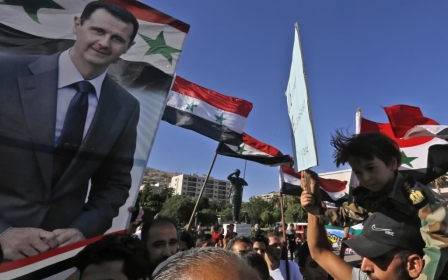

Syria: How do you solve a problem like Assad?

Western leaders face a problem: what to do about Syrian President Bashar al-Assad? Despite their condemnation of his brutality during the decade-long Syrian civil war, including calling for his departure, imposing economic sanctions and militarily backing his opponents, the Syrian dictator remains in power.

His continued survival has exposed the hollowness of western condemnation, with leaders unwilling throughout the conflict to match rhetoric with sufficient action to topple Assad’s regime.

But the Assad problem isn’t going away. With Russian and Iranian support, he has recaptured two-thirds of Syria, ruling reconquered areas harshly while continuing to attack the regions still in enemy hands.

Loyalists and regime insiders have had 10 years of war to overthrow Assad and have not done it, whether out of fear, belief or self-preservation

Moreover, Syria’s economy and state continue to crumble under the weight of sanctions, neighbouring Lebanon’s financial crisis, the legacy of war and deep corruption. Syria is on a fast track to becoming a failed state on Europe’s doorstep.

So what to do? In Washington, a collection of politicians, think-tankers and exiled Syrian opposition figures are urging the Biden administration to pursue policies ultimately aimed at regime change in Damascus. At a recent House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee meeting, for example, the Institute for the Study of War’s Jennifer Cafarella insisted that Assad’s removal remained “an important long-term goal”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But much as they might desire it, regime change is not a likely outcome, and the various methods advocated by such hawks to achieve it are unrealistic.

Economic sanctions

One option is direct military intervention, but this has been off the table since former US President Barack Obama called off a proposed strike on Assad in September 2013, and most DC activists are loath to revive the idea.

Another preferred alternative by some is to keep piling on economic sanctions, such as the harsh Caesar Act. The hope is that destitution will prompt either an internal coup, possibly backed by a frustrated Russia, or a loyalist uprising. Yet, loyalists and regime insiders have had 10 years of war to overthrow Assad and have not done it, whether out of fear, belief or self-preservation.

While there is growing criticism of the regime among loyalists, grumbling is not the same as open revolt or a coup. Assad has shown in the last decade the brutality he’s willing to mete out to rebels, and it is quite a leap to expect those who have stood by him through the last 10 years to be willing to risk everything now.

Moreover, sanctions elsewhere have repeatedly been shown to diminish the chance of internal revolt and increase the grip of a ruling regime, with people even more dependent on it for the meagre resources available.

A final option suggested by some - to negotiate Assad’s departure via his patron, Russia - is also fanciful. The hope is that Moscow could be persuaded to jettison Assad in exchange for guarantees of its position in Syria, but this idea was proposed by former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton earlier in the war and dismissed by Moscow. Why would Russian President Vladimir Putin agree to it now? He currently benefits from Assad’s rule and, whatever American hawks may promise, there is no guarantee that a successor would replicate this relationship.

In contrast to Obama during the Arab Spring, Putin promoted himself as a leader who stands by his embattled allies, so abandoning Assad under western pressure would undermine this. Putin may be happy to give western leaders the impression that he’s open to a transition without Assad in order to persuade them to drop sanctions, but he is unwilling to actually do it.

Risks of accommodation

In all likelihood, then, western-prompted regime change remains a fantasy. This leaves two equally unwelcome options. The first is to continue the status quo: keep Assad isolated and sanctioned, while trying to mitigate the fallout of his rule as much as possible. This includes supporting opposition-held enclaves and humanitarian activities where possible, including for Syria’s many refugees.

The problem is that this will most likely not prevent Syria’s gradual decline and even collapse. Syria could end up like Iraq in the 1990s: strangled by sanctions from the outside and brutal rulers from the inside. State institutions are hollowed out by both, leading to chaos if the government does eventually fall. For western leaders hoping to stem flows of refugees and extremists, as well as to alleviate Syrians’ suffering, this is not desirable.

But the other option is even less palatable: some kind of accommodation with Assad. This would seemingly reward his violence backed by Russia and Iran, emboldening them and autocrats elsewhere. It would also make a mockery of the humanitarian and liberal principles western governments say they strive to promote.

Yet, others have argued that this is the practical, realistic course of action. Having failed to topple Assad, it makes more sense to allow the Syrian economy and state to recover, rather than to squeeze it to the point of collapse. Optimists might say it is more likely that loyalists would overthrow Assad if trade was reopened, as they would be less dependent on the regime.

A more pessimistic take is that Assad and his cronies would benefit the most from any dropping of sanctions, but at least that might make Syria more stable and less inclined to disrupt the region as they protect their gains. Of course, this also carries the risk that Assad profits from the reopening, and continues to disrupt the region and brutalise his people, who don’t rise up - but this time, western leaders would be culpable for accommodating him.

For this reason, it seems highly unlikely that any western leader will risk normalisation. Indeed, the G7 recently reiterated its opposition to Assad, declaring the presidential elections scheduled for 26 May as illegitimate and opposing any normalisation. This leaves the status quo as the most likely approach, with Assad’s state continuing to crumble, but not likely to fall any time soon.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.