A time will come, when there will be a real eruption

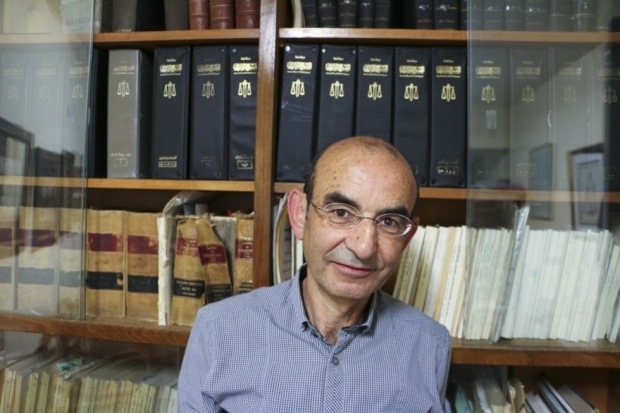

Sitting on a leather armchair that oversizes his fragile build, in his Ramallah law office, located on one of the main streets of this bustling city, Raja Shehadeh speaks softly and calmly about turbulent decades of life under the occupation.

“Do you ever wonder why people throw trash in the streets?” he asks. He answers right away: “People lost a sense of control over their lives and over public spaces. The public space is not yours, so what does it matter if you make it dirty? There is a general sense of disempowerment.”

“When there is a feeling that small individual action matters, things will change. In the first Intifada, I saw how people believed that small actions could build up to something big. And I don't see it now.”

Before 1948, Ramallah was merely a town in the windy hills of the West Bank, where families of Jaffa used to come to flee the summer heat and humidity of their seashore city. But in 1948, Raja's family and thousands of others fled from Jaffa to Ramallah, to avoid the attacks of the emerging Israeli army. As everyone else, they believed this was temporary, and once the military fighting was over, they would come back. Instead, their grandmother's summer house, which Raja's parents believed to be a temporary shelter, became their new home.

In 1967, Israel conquered and occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Generations of Palestinians took up the struggle against the occupation; each in their own way.

Different struggles

“For me, the way I struggled, was through human rights. In the case of my father - he thought it was too late already, and what would be the benefit of the human rights struggle? We needed a political struggle, he thought. He could not see that the human rights struggle was also one form of a political struggle. So, he did not have much hope or appreciation for my choice and that created a conflict, compounded by psychological [issues],” he says. His book entitled, Strangers in the House is an intimate account of family life torn by politics and unfulfilled expectations.

His approach at the time was “an unknown area.” “People would say, ‘human rights? What's that about? The only struggle is our political struggle!’” Shehadeh, together with other lawyers, was launching the first independent human rights organisation, Al-Haq in 1979. He debated with his father regarding their ideological choices, many Palestinians chose to take up arms. Shehadeh admits that he “missed that all together.”

“It took me a long time to realise how important it [the armed struggle] was. It wasn't the question of would it work or would it not work. It was an emotional thing. Palestinians had been suppressed and denied expression of their national identity and it was very important to regain the awareness of for whom they are struggling. Now, the armed struggle ended up without bringing any concrete benefit, but this is beside the point.”

Over the years of Israeli closures and the policy of separating Jerusalem from other Palestinian cities of the West Bank, Ramallah took on the role of the informal Palestinian capital. Today, the construction does not stop, and upscale cafes, catering to the needs of the Palestinian middle class and well-off international community, spring up on every corner.

“These are confusing times,” says Raja Shehadeh. The encouragement to consume and to take loans limits people's willingness to participate in resistance.” There has been so much effort by Blair-type people [Tony Blair, Special Envoy of the Middle East Quartet] to distract society with bank loans, money, material things. People are busy paying back their loans and would be hesitant to sacrifice their work by going to protest, or participate in a strike.”

Despite that, he retains a certain optimism. He believes that it will not work for long, that people eventually will demand their rights and dignity. “The differences between Palestinian and Israeli life today are so great, they cannot go unnoticed. The fact that a young man, a 16 year-old Palestinian, can be killed, because an Israeli soldier was bored, cannot go unfelt on a large scale. A time will come, when there will be a real eruption.” he says, referring to the killing of two Palestinian boys Nadim Nawareh and Mohammed Salameh. The two boys were gunned down in Beitunia village, neighbouring Ramallah, during a protest commemorating the “Nakba”, when roughly 700,000 Palestinians were expelled from their lands in 1948.

Smuggling manuscripts out

Raja Shehadeh keeps his legal work “not to get stuck at home writing, and to stay exposed” to what is happening in the world. And there are important changes taking place in Palestinian society, especially between generations.

“You know, during the first Intifada, when I was writing books, it was a big deal to smuggle out a manuscript. Mail was of course censored. We hardly had telephones. There was no email. We kept on sending things with people going through the airport. And risking. You never knew if they would be checked at the airport, and they often were.”

But times have changed. “Now, you do it without thinking. You just press the buttons, and the script goes. So different times have different challenges and different means of dealing with those challenges.” He adds, “The new generation turns to new methods of organising, that did not exist before, through social media, and they are good at it.”

Even more dramatic changes fell on those ancient hills around Ramallah, where once his grandfather would set out on sarhas, wanderings, walking among nature. Raja followed in his footsteps and became a passionate walker, lovingly painting portraits of the disappearing landscapes in his book, entitled, Palestinian Walks. The last walk he took was with a group of writers who came to Ramallah to participate in PalFest, a literature festival. It is one of the events that testifies to the cultural revival taking place in Palestinian society. He explains, “I usually don't like going with a big group, but for them I made an exception. They were very nice and appreciative people.” Raja guided them to one of the kasrs, a simple stone building in the fields, used by the farmers to store harvest and sleep during the days of work. He sat there with the writers and read passages from the book, “so they could get a sense of those hills.”

According to Shehadeh, the cultural eruption is a result of the shift in focus among many people from politics to culture. “When I was growing up, I did not see so much of the visual arts. And now wonderful things are coming out.” He says similar trends applied to composing and performing music, drama and writing.

Unity – the first step

But even politics, for once, seem to be going in the right direction. Shehadeh considers the new unity government between political parties, Fatah and Hamas a great achievement. Since 2006, Palestinians in the West Bank and Palestinians in Gaza were ruled by two separate entities, with separate civil servants and security forces.

Raja thinks that “it will not be easy to bring unity back on all levels and it will be a bumpy road, but, the important thing is that it started.” He says that in the end, it is a necessary requirement to achieve a negotiated agreement with the Israelis. “Even if Kerry’s [peace initiative] had been successful, it would not have included Gaza.” He quickly remembers that the main obstacle lies on the other side, “Also, hopefully, there will be elections in Israel, and a new government that wants peace will be elected, but that does not seem very likely.”

Nothing shakes his conviction that the struggle will end through negotiations. “One cannot lose faith in negotiations. But the conditions under which negotiations take place make all the difference.” The last round of talk was doomed, in his opinion, “because the Israeli government did not want to negotiate or take political risks and the United States, the sponsor, was not applying pressure on the Israelis. So, from where was changed supposed to come? From talking?”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.