Egypt: Hadid sisters join calls to free TikTok influencers

International supermodel Bella Hadid and her fashion designer sister Alana Hadid have joined growing calls for the release of Egyptian TikTok influencers Mawada al-Adham and Haneen Hossam, who have been convicted of human trafficking.

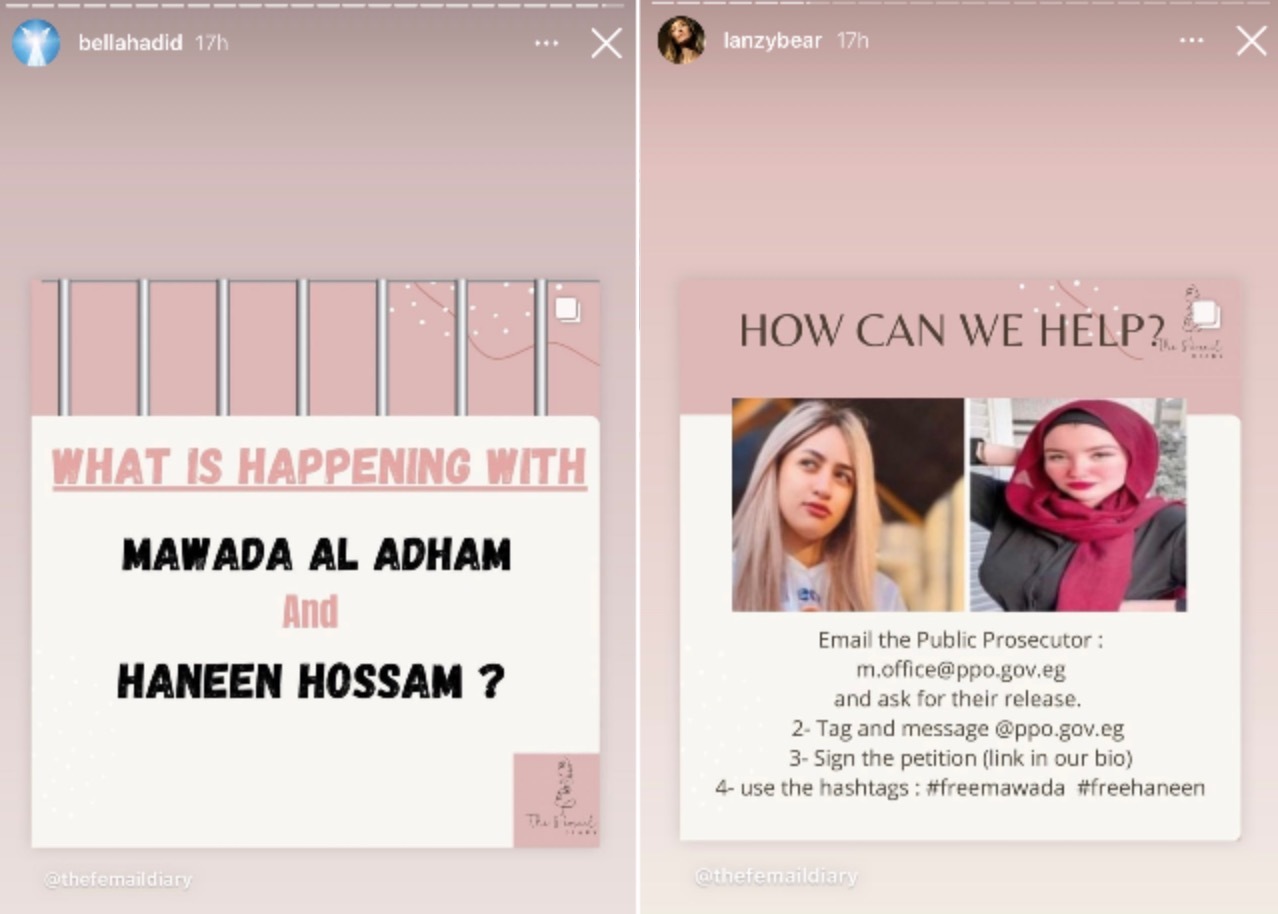

On Wednesday evening, the Hadid sisters shared an informative post about the influencers, following an Egyptian court’s decision to sentence them to prison and fine them, after they were accused of exploiting girls through video-sharing apps.

The Hadids added the hashtags #freemawada and #freehaneen to their posts in support of al-Adham and Hossam.

The post, which has over 3,000 likes, was originally placed on the Instagram page The Femail Diary, an online campaign launched by Merhan Keller. Reem Abdellatif, a friend of Keller's, who is also a human rights advocate and journalist, later joined the The Femail Diary as a supporter and content creator.

The campaign explains what happened to the TikTok influencers and how people can help campaign for their freedom.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“Since social media technicalities and monetisation are still foreign and new concepts not commonly considered by the Egyptian judiciary, prosecutors equated these ads to human trafficking," the post states.

“Mawada and Haneen are two young girls who are not a danger to society nor wanted for any other crimes. Both girls are in a very bad shape, their health is deteriorating and their lives have been completely disrupted,” the post adds.

'Human trafficking' charges

Abdellatif told Middle East Eye that she joined the platform Keller created, The Femail Diary as a result of growing frustration and the need to dedicate a space to Egyptian women and female prisoners of conscience, who she says are a minority within a minority in the country.

"Initially, Keller launched The Femail Diary as a way to create a safe space for Egyptian women and girls, where they could discuss issues most important to them, whether that's bodily autonomy, sexuality, or personal healing to overcome generational trauma,” she explained.

'Mawada and Haneen are not human traffickers. They figured out a way to monetise social media. Egyptian law must be reformed to reflect a new global digital economy'

- Reem Abdellatif, women's rights activist

Much debate has been raised about the human trafficking charges against al-Adham and Hossam, with many unable to see the corralation between their social media content "violating societal and family values" and the charges.

Keller says she urges the Egyptian government to assign an expert to advise on the monetisation of social media apps, and explain to the courts that this does not equate to human trafficking.

"We understand the generational gap and that social media is very under discovered, especially in court in Egypt, and this is precisley why we must revisit many of our laws and amend them according to the present day economy," she said.

Echoing the statement, Abdellatif says the legal system in Egypt is largely to blame for this, as it does not consider the evolution of social media and the new ways in which it can be used to generate income.

"This is why we directly address the public prosecutor and ask Egyptian President Sisi to take action. We have hope and faith that they may understand our pleas, particularly since these young women are not a danger to anyone and their mental and physical health is deteriorating due to the trauma they've faced from this trial," she said.

Abdellatif has called for reform of Egyptian law, as social media continues to grow in the country and young, savvy users find new ways to earn an income from it.

“Mawada and Haneen are not human traffickers. They figured out a way to monetise social media. Egyptian law must be reformed to reflect a new global digital economy. The legal system in Egypt is far behind, and sadly these laws are sometimes misused to repress women unaffiliated with the state. We hope instead the state will embrace women, girls, and young people who are ready for change,” Keller said.

Keller also said that knowing Hossam and al-Adham personally made her even more determined to speak out.

"I know Mawada and Haneen personally and I have all the case information, files and lawyers' feedback... Mawada and I had the same lawyer at one point so I was involved in her case from day one and I was aware of the false rumours spreading online," she said.

For Keller, the Hadid sisters sharing the post was significant in raising awareness of the case.

"It meant the world. The girls come from a humble background and they were not getting any attention until the Hadids spoke. I hope that more international celebrities join in the calling for justice," she added.

Abdellatif says that the charges against the women could be seen as an attempt to silence women, particularly as many have been using social media to speak out in recent years.

"I do believe this is an attempt by the Egyptian public prosecutor to rein women in after we made a massive impact to break the silence over a couple of years with the #MeToo movement in Egypt," she told Middle East Eye.

Prison time and fines

Last week, al-Adham was sentenced to six years in prison, while Hossam was sentenced to 10 years, both with a fine of 200,000 Egyptian pounds ($12,700).

Adham had over three million followers on TikTok, where she used the platform to share videos of herself lip-syncing and dancing. Hossam, who has a following of one million, uploaded footage detailing how others could use the app to earn money.

The two young women had been tried over accusations that they were “using girls in acts contrary to the principles and values of Egyptian society with the aim of gaining material benefits”.

According to local media, the prosecution accused the influencers of "exploiting" people from disadvantaged economic backgrounds by promising them money, and also of belonging to a criminal group - arguing that such charges amounted to human trafficking.

Earlier this month, another TikTok influencer, Renad Emad, was sentenced to three years in prison and fined 100,000 Egyptian pounds ($6,350) over her content, which was deemed to violate societal values as well as amounting to human trafficking.

International condemnation

A number of journalists and human rights experts have previously condemned Egypt’s cybercrime laws.

Not only can authorities use them to imprison and fine people for content posted online deemed to be inconsistent with "family principles" or the values of Egyptian society, but the law also allows any social media accounts with more than 5,000 followers to be monitored.

“Egyptian law is very vague and broad," Amr Magdi, a Middle East researcher at Human Rights Watch, previously told Middle East Eye. "They talk about acts which undermine family values, but the law does not define what these acts are, so citizens do not know when they are violating the law. The punishments for these acts are also extremely disproportionate.”

Last year, rights group Amnesty International issued a statement calling on Egyptian authorities to end their crackdown on women TikTok users, adding that they were being prosecuted on "absurd charges of indecency and violating family principles and values".

In a statement at the time, Lynn Maalouf, Amnesty International's Middle East and North Africa research director, said that their arrest perpetuated a culture of inequality and violence against women.

“Instead of policing women online, the government must prioritise investigating the widespread cases of sexual and gender-based violence against women and girls in Egypt,” she said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.