Reading Nubian: Books for a new generation discovering their language

When Ramey Dawoud looks back on his childhood days in the Egyptian city of Alexandria, he recalls hearing the adults around him speak in their native language: Nubian.

Yet with him they’d automatically switch to Arabic, the language used in his school and, inevitably, the one he would grow up speaking, instead of the language he now considers his mother tongue.

Dawoud’s family originated from a city in northern Sudan called Wadi Halfa, near the border with Egypt. Following the construction of the Aswan High Dam, in 1964 Wadi Halfa was flooded, and tens of thousands of people were displaced. His family was forced to relocate hundreds of kilometres away, to a new site that would be known as “New Halfa” in eastern Sudan.

It was in the 1990s that his family moved to Alexandria, where Dawoud was born. Nine years later, they moved again, this time to the United States, where a young Dawoud began to speculate about his roots.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“It was in high school in America, as a teenager, when I rediscovered my identity,” Dawoud tells Middle East Eye.

“I began researching about Nubian history and about the language. And I was wondering: how come I speak Arabic but then I would hear my grandmother speaking in a completely different language. Then it was when a seed was planted in me, going on this journey of learning who I am.”

As Dawoud began reading and studying Nubian culture, he realised that fewer and fewer people were speaking this language, and that it was becoming endangered.

As part of his efforts to help preserve the language - which included writing hip hop songs with Nubian lyrics - he decided to write a children’s book in Nobiin, the most widely spoken of the Nubian languages, prevalent in Upper Egypt and northern Sudan.

He would quickly discover that he wasn’t alone in his quest.

At the time, Hatim Eujayl, a Sudanese illustrator and Nubian font designer, was discussing a similar project with Joel Mitchell, the founder of Taras Press, a private press and type collection in London. After making contact on social media, they realised their goals were aligned and decided to collaborate instead.

The result will be the forthcoming publication of four children’s books written in the centuries-old Nubian alphabet found in Old Nubian manuscripts.

Their immediate goal is to help Nubians like them, as well as anyone else who happens to be interested in these languages, learn to read, write and count in Nobiin.

Endangered language

Nobiin belongs to the family of Nubian languages spoken in Sudan and southern Egypt. And it’s a close relative of Old Nubian, a literary language written in the Nubian kingdoms of Nobadia and Makuria from around the 8th century up to the 15th century, Vincent WJ van Gerven Oei, a philologist specialising in Old Nubian based in The Hague, tells MEE.

Van Gerven Oei notes that the written Old Nubian language was contemporary to Old Nobiin, the spoken vernacular ancestral to present-day Nobiin, a term that was coined in the mid-20th century by scholars.

The prevalence of Nobiin in the areas where it is spoken started to be challenged by Arabic from the 12th century, in a process that accelerated with the gradual Islamisation of Nubia, accompanied by the decline of the Christian Nubian kingdoms.

In modern times, Nubia has been divided between Egypt and Sudan, two largely Arabic-speaking countries that have historically denied cultural diversity and multilingualism, and have a mostly monolingual education system.

This context has led to cultural marginalisation and a gradual cultural cleansing of the Nubian communities, as noted in a 2020 report on Nobiin by linguists Maya L Barzilai and Nubantood Khalil.

Other dynamics, such as labour migration and urbanisation, and several waves of displacement during the 20th century, the largest of which was caused by the construction of the Aswan High Dam, have put Nobiin at even higher risk.

The loss of what had been the main writing system of the Nubian people for at least eight centuries created a deep gap in the written history of these languages

“The current status of Nobiin is threatened [according to the EGIDS vitality ranking] and, following Unesco, the language is vulnerable, [as] the language is used orally by all generations but only some of the child-bearing generation are transmitting it to their children,” van Gerven Oei said.

It is estimated that just over half a million people speak Nobiin today. Most of them live in Sudan and Egypt, and the rest in the US, Europe and the Gulf, according to Barzilai’s and Khalil’s report.

Even though a native alphabet was consistently used to write Old Nubian until the collapse of the last Nubian kingdom in the 16th century, many people today still believe that Nubian languages are unwritten. The loss of what had been the main writing system of the Nubian people for at least eight centuries created a deep gap in the written history of these languages.

Attempts to write Nobiin again date to the 19th century missionary efforts in the region, van Gerven Oei says. But the revival of the alphabet started with the wider spread of knowledge of Old Nubian among Nubian communities in the later 20th century.

One of the most prominent initiatives to redevelop Nobiin writing methods was led by a Nubian professor at Cairo University, Mukhtar Khalil Kabbara, in the 1990s. Kabbara simplified and defined modern Nubian orthography in a way that still influences how people write Nubian today.

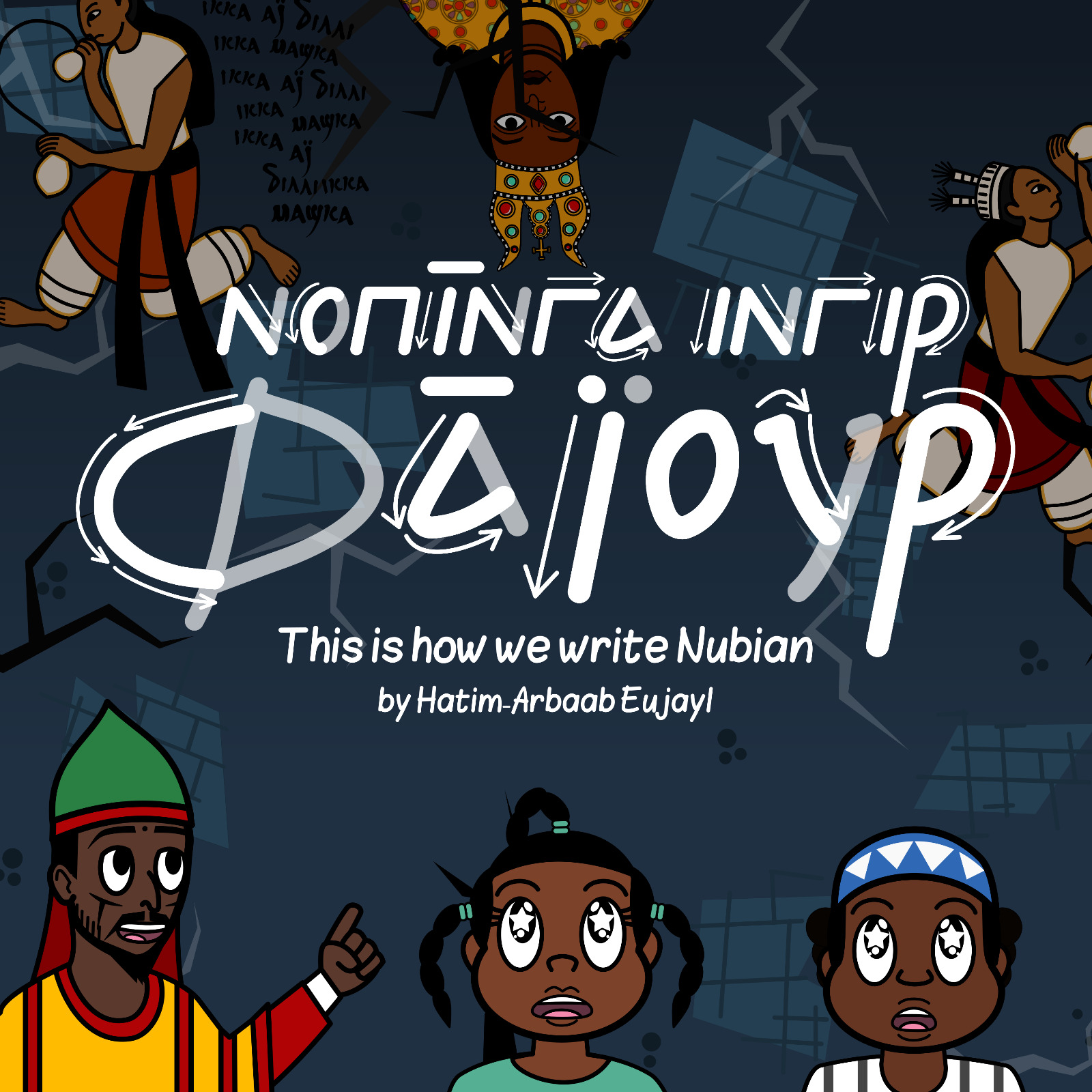

This is how we write Nubian

Having teamed up with Mitchell, the publisher and founder of Taras Press, and K. Eltinae, a Sudanese poet of Nubian descent, Dawoud and Eujayl are now carrying on the work of Kabbara and others involved in the revival of the Nubian alphabet to write Nubian scripts and the preservation of the Nobiin Nubian language.

With the help of Taras Press, the team aim to continue making the Nubian language and its alphabet more accessible.

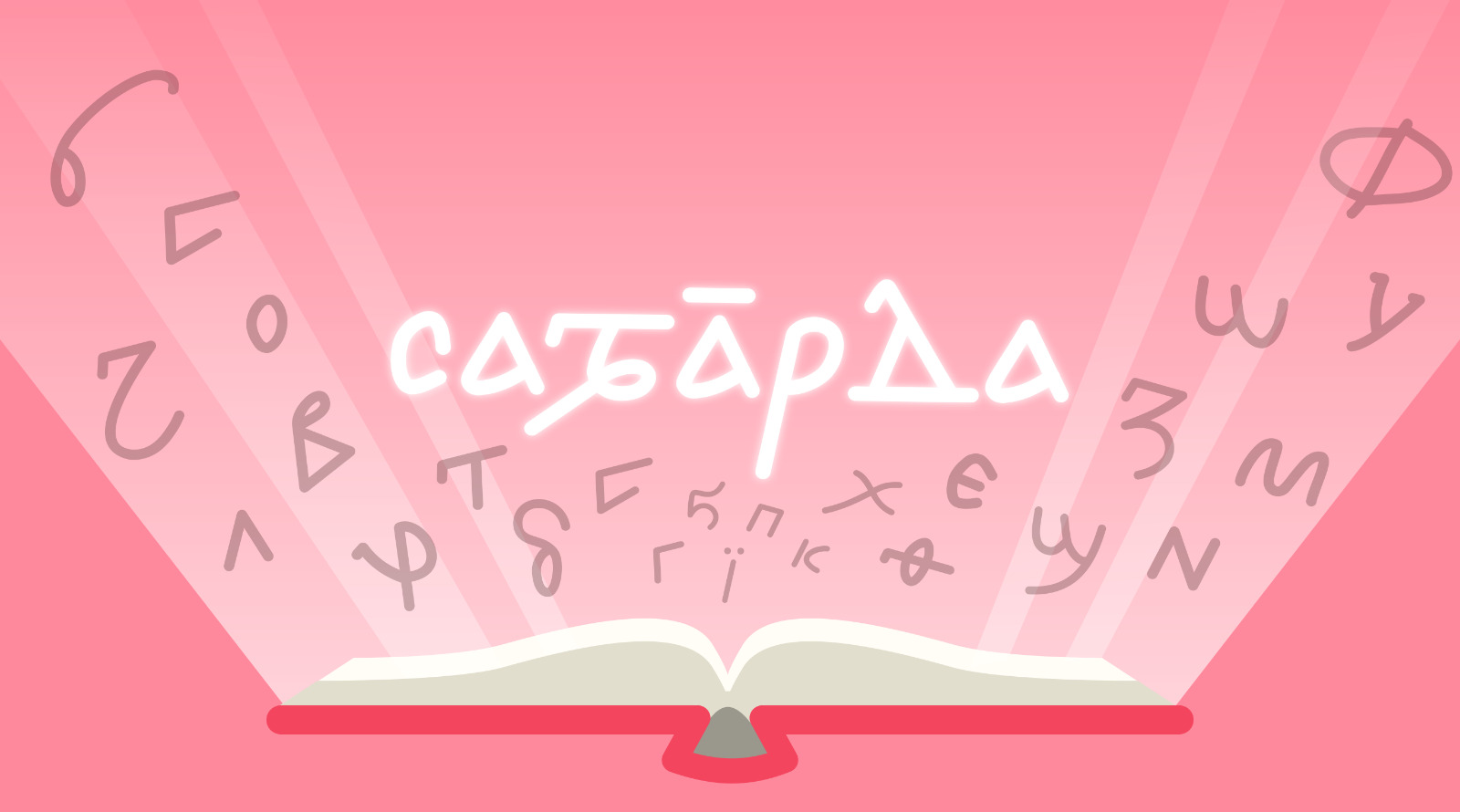

Eujayl developed a font he’s named Sawarda (after the town to which his family traces its origins, and the birthplace of renowned Nubian singer Mohammed Wardi), based on Old Nubian manuscripts, with the help of van Gerven Oei. It is the world’s first font especially designed for the Nubian language and will be the sole font used in all four books the team plan to produce, to ensure that the Nubian script accurately represents the Nubian writing tradition.

“With other books written in modern Nubian, everyone is disappointed by the way they look because the fonts are not suitable, they don’t look well produced, they are not refined. And I think the font project we are working on as part of this will add extra value to the publishing sphere for Nubian,” Mitchell says.

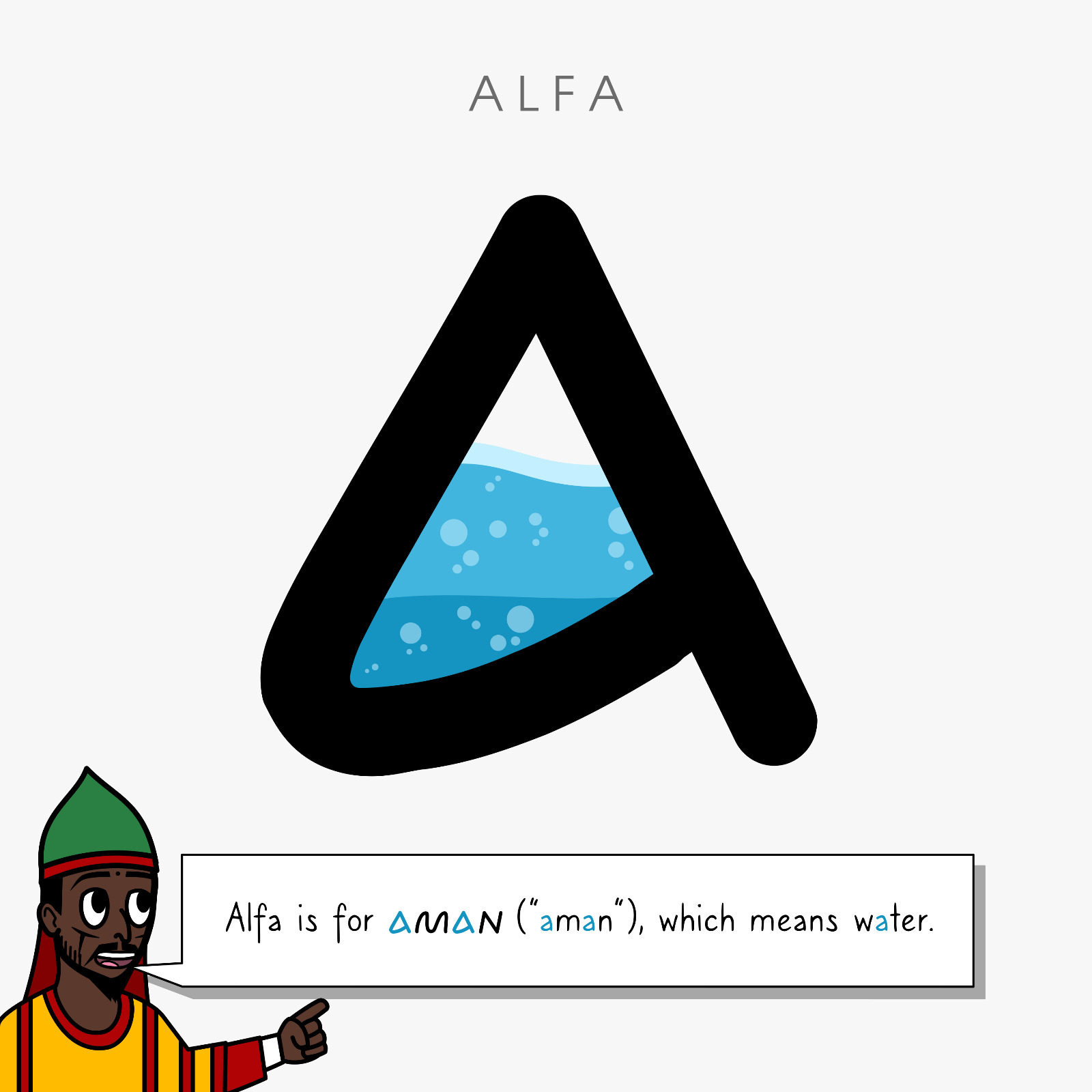

Aimed at children aged 3-6, the first book, This is How We Write Nubian, is an alphabet book that will educate people on how to read and write each Nubian letter. The book introduces the Nubian script and basic vocabulary to early readers by connecting the letter in each page to specific words in Nobiin containing that same letter. The process is guided by the book’s main character: an ancient Nubian scribe called Yosefi.

“The example is Alfa, from Aman, which looks like the letter A and it’s filled with water because Aman, in Nobiin, means water,” Eujayl, who wrote two of the four books, told MEE. “It will be really important in helping people become familiar with the script,” he added.

As part of the team’s efforts to encourage Nubian literacy, they have been teaching how to write one Nubian letter a day on social media through animated clips accompanied by historical examples. On 21 June, at the end of the series, they launched a writing challenge to put in practice what had been learned in three simple Nubian phrases.

Nabra’s Nubian Numbers, written by Dawoud with translations in English and Arabic, is a picture book that teaches counting, and focuses on Nubian numbers from one to ten. In the book, each page will be dedicated to one number, and each of them will be used in a sentence and connected to an illustration representing an aspect of Nubian culture. The book will also have transliterations, and its main character is a Nubian girl called Nabra, which means “the golden one”.

“I am teaching the numbers and how to use [them] in a sentence. Through the illustrations and contents, I am also promoting Nubian culture. It is not random things we are counting; we are counting things that have to do with everyday Nubian life,” Dawoud explained.

The third one, Sisters of the Water, is an illustrated storybook written by Eltinae in English, which interweaves Nobiin vocabulary, and it aims to help build vocabulary.

The book touches upon the raising of the Aswan High Dam and Nubians’ collective nostalgia for a place that was lost through the story of a little Nubian girl, Zanooba, who finds three cowrie shells on the beach near the Red Sea and puts them under her pillow. At night, the shells magically transform into three wise mermaids, who represent the past, the present and the future, and take the girl on unforgettable adventures across the Nile Delta to better understand her heritage and place in the universe.

“Through these adventures there’s a lot of basic words, like shapes, colours, that readers are exposed to in Nobiin. It’s educational, but at the same time it has an element of magic,” Eltinae says.

“First and foremost, [the project aims] to make sure children grow up understanding and being exposed to Nubian, and hopefully the project will achieve this. It is also a way of preserving a language,” he added.

The last book, The Miracle of Amanirenas, is a storybook by Eujayl that will be published in two bilingual editions English/Nobiin and Arabic/Nobiin, and is aimed at building on the literacy and vocabulary skills from the other books. Set in a Nubia-inspired fantasy world, the book tells the story of the founding of the Kingdom of Mubia (a variant name used on purpose), in which the Nubian people try to resist the tyranny of an emperor.

“It is a fantasy book; it is not historically accurate and it does not pretend to be. It combines a bunch of different periods in history and also a bunch of different stories,” Eujayl noted.

“It synthesises the story of the wise stranger, a collection of different stories you will find in different Sudanese cultures, with the story of the real-life Kandaka Amanirenas [a Nubian queen who battled and defeated the Romans], and [combines] that with the story of Mek Nimr, who is a Sudanese anti-colonial hero. And I kind of merge all those together with a little bit of pan-Africanism,” he added.

The book series will also be the first time Taras Press publishes in Nubian. This press and type collection formally began working two years ago, but until now it has focused on small projects of experimental literature and poetry in Arabic and Syriac, and translations into English, Mitchell told MEE.

During this period, he has also been involved in projects of digital typography and the design of fonts for computers.

“To really get interest in this [project] we needed to create a community of readers and have books for different ages. And the four books kind of work for a whole range, from very beginner learners up to sort of teenagers,” Mitchell says.

Codifying Nubian orthography

With the publication of the books, the team first aims to expand the small genre of Nubia-related and Nubian-language literature for children, in what they see as a key step to help preserve the language. “My hope is to provide that kind of thing that was missing for other generations, because the children in the past did not have Nubian children's books,” Eujayl said.

Muram Shaheen, a 22-year-old student of architecture living in Khartoum, agrees. “I am Nubian but I don’t speak [the language], which sometimes is a shame. I am trying to learn it right now, but I find it very hard as a grown person,” she tells MEE.

“I only know two people [of my generation] who speak it, and not fluently. And the written is completely disappearing,” Shaheen added, noting that, as a child, she was not exposed to any Nubian literature.

“This [project] is the type of [content] I want my children to consume.”

At the same time, the team is investing a great deal of its efforts in reconciling Nobiin’s orthography, a procedure that they consider fundamental to the learning process. Mitchell explained that, because Nubian went through centuries of being an oral language, people writing in Nubian today don’t use the traditional orthography. They have also changed some aspects over time in a way that is not necessarily consistent.

To remedy the situation, the group has developed the first font that accurately represents the Nubian manuscript culture and is trying to codify Nubian orthography.

'The success of the project is uplifting - how many people are still interested in making sure that Nobiin is taught to their children, spread around the world, not letting a language disappear'

- K. Eltinae, Sudanese poet of Nubian descent

“It is not that we are going to put these books out and they will be consistent. But we are consulting with community groups, scholars and linguists, and we invite anyone, [as] we want to build consensus and maybe some compromises around how Nubian language is being written, so that [people] don’t have a moving target,” Mitchell said.

Last May, the project secured the necessary funds to move forward thanks to a crowdfunding campaign.

“The success of the project is very uplifting to see, how many people are still interested in making sure that Nobiin is taught to their children, spread around the world, and it is not letting a language disappear,” Eltinae said.

With the funds to publish the books secured, the team is also beginning to set their eyes on getting them into as many hands as possible, especially in Sudan and Egypt. Due to the urgency to preserve the language, free digital editions of all books will be made available.

“One of the most despicable things is how inaccessible information on Nubia is to Nubians, either because it is locked behind a paywall or because it is locked away due to a language barrier. A lot of the material and research is in English,” Eujayl said.

Already building on their initial success, and with an eye to the future, the team is also considering making audio books of these editions as well as doing translations into a second Nubian language group, Andaandi and Matoki. They hope that these will become part of a long-term initiative to continue publishing other books.

“I would love to see that there is someone who gets inspired by this to do the same with their own native language, and I would like to see all indigenous languages get the respect that they deserve,” Dawoud says.

The four books will be available from Taras Press later this year

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.