Hajj: When is it, how did it start, and other key questions explained

Over the next week, Muslim pilgrims will embark on the annual pilgrimage of Hajj, which takes place in Saudi Arabia.

It is a religious obligation on all Muslims who are healthy, financially able, of sound mind and of age to perform the pilgrimage at least once in their lifetime.

Middle East Eye answers some key questions about the timing, history and rituals of the most important pilgrimage in Islam.

When is Hajj?

Hajj takes place each year across several days during the month of Dhu al-Hijjah, the 12th and final month of the Islamic lunar calendar.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

As the lunar calendar is 11 days shorter than the Gregorian calendar, the Gregorian date for Hajj changes each year, and over time the pilgrimage falls within all months and seasons.

This year, the first day of Hajj is expected to be on Friday 14 June.

How do Muslims perform Hajj?

The Muslim pilgrimage takes places across a number of significant locations in Saudi Arabia.

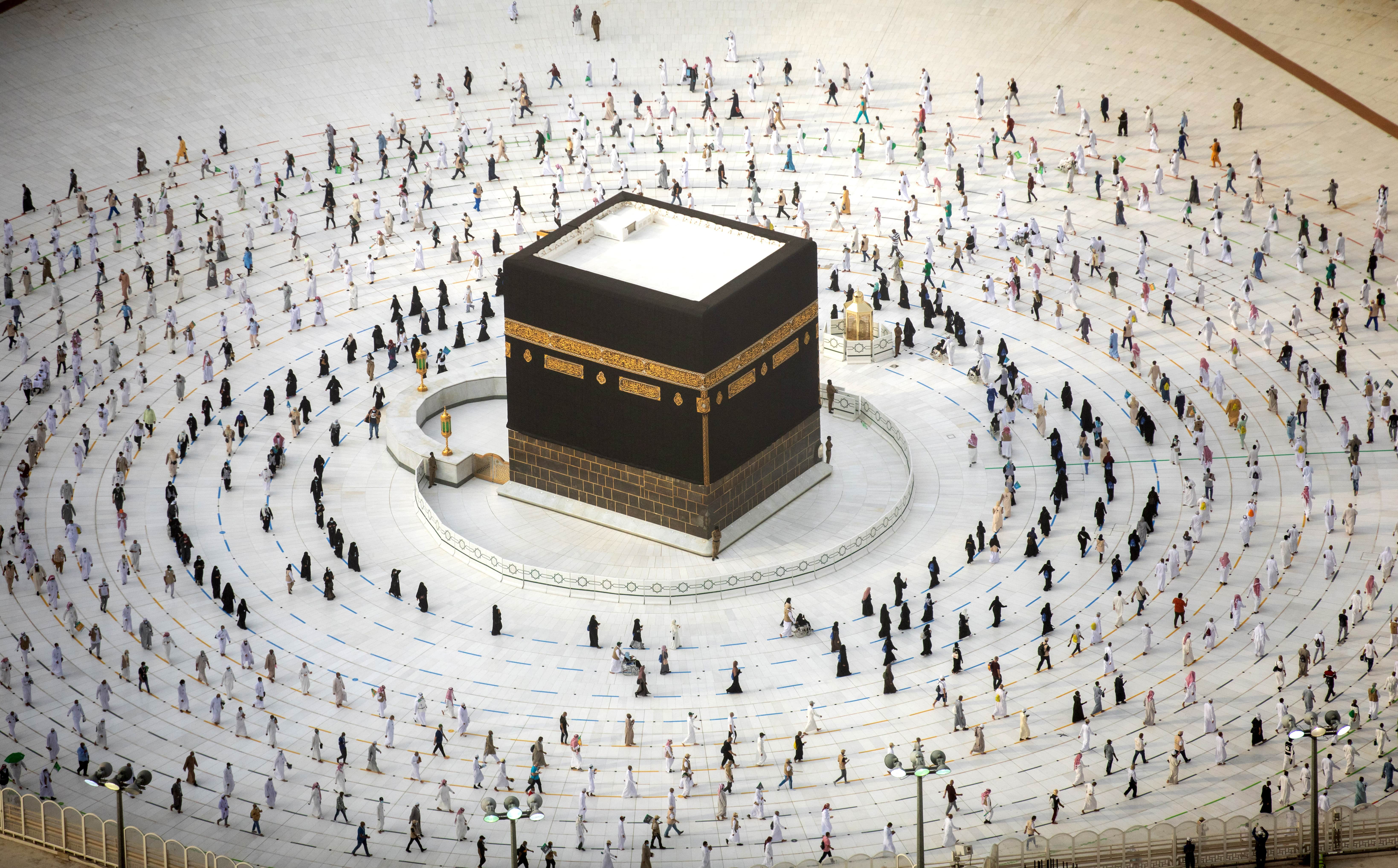

It traditionally begins in Mecca, where pilgrims take part in the year-round Umrah pilgrimage. This consists of tawaf, circling the Kaaba counter-clockwise seven times, and walking between the hills of Safa and Marwa.

Pilgrims then spend a day praying in the valley of Mina, before heading to Arafat, some 20km east of Mecca.

On the Day of Arafat, pilgrims spend the entire day near a hill known as Mount Arafat (the Mount of Mercy), where the Prophet Muhammad delivered his final sermon. This is considered to be a great day of forgiveness, and is spent repenting for past sins.

Pilgrims then spend a night in Muzdalifa, an area between Arafat and Mina, where they pray and gather pebbles.

The pebbles are used in a symbolic stoning of the devil the following day. Three pillars - small, medium and large - are stoned by pilgrims in Mina, where Muslims believe the devil attempted to dissuade Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) from obeying God’s commands.

After the stoning, an animal is sacrificed to mark the first day of Eid al-Adha, when Muslims commemorate the willingness of Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) to make any sacrifice commanded of him by God.

Hajj pilgrims then proceed to cut their hair, as a sign of renewal. While men may shave their heads or cut their hair short, women are only required to cut a lock of hair.

The pilgrims conclude Hajj by returning to Mecca for a final tawaf. Although not a part of the Hajj itself, many people round off the pilgrimage with a visit to the holy city of Medina, where the prophet is buried.

What do pilgrims wear during Hajj?

All pilgrims remain in a special spiritual state of holiness, known as ihram, during the Hajj. This includes wearing simple clothes, which for men consist mainly of two pieces of white, unsewn cloth. Women are not restricted to a specific colour, but are also encouraged to wear non-elaborate clothing.

The ihram is aimed at nullifying differences between people based on their material wealth, with all pilgrims equal in front of God, irrespective of wealth, nationality or race.

Notably, American activist Malcolm X found the experience of seeing Muslims of different backgrounds and complexions interacting equally during Hajj to be a transformative experience, altering his previous thinking on the relationship between races.

Other aspects of ihram include refraining from cutting one's hair, clipping nails, having sexual relations and using perfume. Ihram ends once pilgrims cut their hair during the final days of the pilgrimage.

How did Hajj begin?

Although the rituals of Hajj began during the time of the prophet, the origins of the pilgrimage date back over 4,000 years.

Around 2000 BCE, Muslims believe that Ibrahim was ordered by God to leave his wife Hajera (Hager) and infant son Ishmael in the desert. With Ishmael dehydrated and very hungry, Hajera ran back and forth between the hills of Safa and Marwa, before praying for deliverance. According to Islamic tradition, it was then that an angel appeared and created a fresh spring of water, known as the well of Zamzam.

Muslims believe that Ibrahim returned to his family, and was ordered by God to build a monument (the Kaaba) at the site of the well, as a gathering place for those who wanted to strengthen their faith in God.

The monument and availability of water turned Mecca into a busy and profitable city. However, over time the Kaaba lost its monotheistic purity, and became a place of idol worship and polytheistic religious practice.

In the year 630, the prophet led his followers from Medina to Mecca, destroying the idols and re-dedicating the site to the worship of the one God. Two years later, he performed the first ever Islamic pilgrimage, laying out to his followers the rituals of the Hajj.

How do pilgrims reach Mecca?

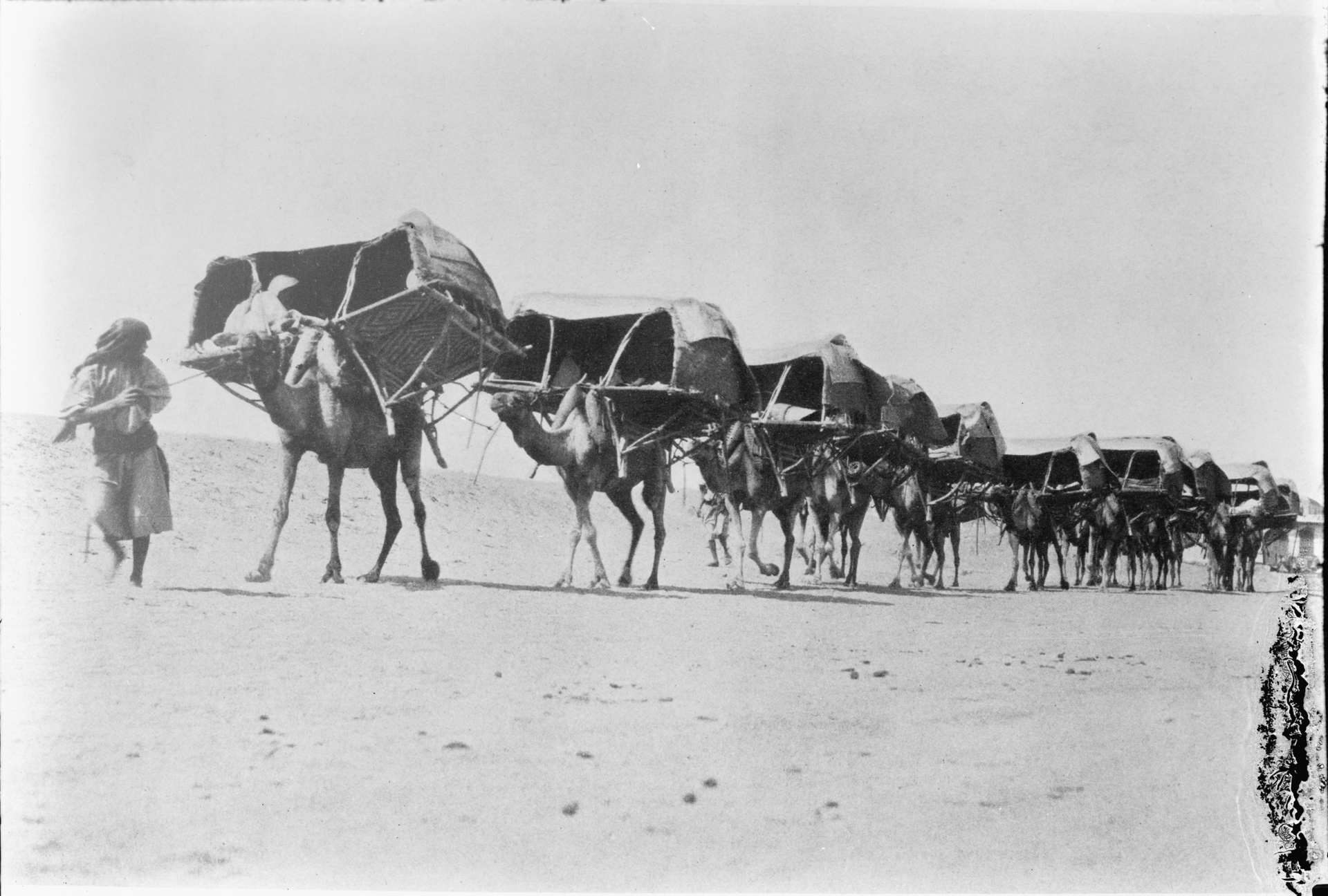

In the first few centuries of the Hajj following the early spread of Islam, pilgrims gathered in large groups in Syria’s Damascus, Egypt’s Cairo and Iraq’s Kufa to travel in caravans to Mecca.

The caravans were often sponsored and organised by Muslim rulers, who took charge of organising the logistics for the pilgrimage. The Ottoman empire was one of the most ambitious patrons - fortifying long stretches of desert Hajj routes to protect caravans from attacks by bandits.

The journey was mostly undertaken on camels, and would take between two to three months on average. The large-scale interaction of thousands of people from different parts of the world led to the Hajj journey becoming a major centre for trade and commerce.

In more recent centuries, performing Hajj became a mass event available to poorer Muslims after the introduction of steamships and railways. Pilgrims often packed themselves onto Arabia-bound steamships on fourth-class tickets - a subject tackled by Joseph Conrad in his 1900 novel Lord Jim.

Since World War Two, the number of pilgrims has increased dramatically, from the thousands to the millions, thanks to accessible air travel.

Have there been disruptions to Hajj?

Throughout history, Hajj has been impacted by wars, plagues and tragedies.

One of the earliest and most severe disruptions came in 930, when the Qarmatians, a now extinct sect within the Ismaili Shia tradition, raided Mecca. The once-powerful movement, which ruled much of eastern Arabia, stole the black stone of the Kaaba and desecrated the well of Zamzam, believing Hajj to be a pagan ritual.

The pilgrimage was cancelled for two decades, until the ruling Abbasid caliphate paid a large ransom to return the stone.

Politics, too, has disrupted Hajj. In 983, disputes between the rulers of the two caliphates - the Abbasids of Iraq and Syria, and the Fatimids of Egypt - prevented Muslims from performing Hajj for eight years.

In 1987, clashes between Shia pilgrims, inspired by the Iranian revolution, and Saudi security forces left over 400 pilgrims dead, mostly Iranians.

Disease outbreaks have also caused cancellation and devastation.

A plague from India hit Mecca in 1831 and killed three-quarters of the pilgrims. A series of epidemics in the following three decades meant Hajj was halted three times, including an 1846 bout of cholera which killed more than 15,000 people in the holy city.

In more recent years, Hajj tragedies have centred around stampedes and overcrowding. The most serious instances were in 1990, when a stampede inside a tunnel near Mecca led to over 1,400 deaths, and in 2015, when over 2,000 people were killed in a crush in Mina.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.