Tensions between Washington and Tehran are adding fuel to Middle East crises

On 5 August, Ebrahim Raisi was officially inaugurated as the new president of Iran. Over the last two years, the Iranian economy has been in recession largely due to former US President Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” policy, implemented since his administration withdrew from the nuclear deal in May 2018.

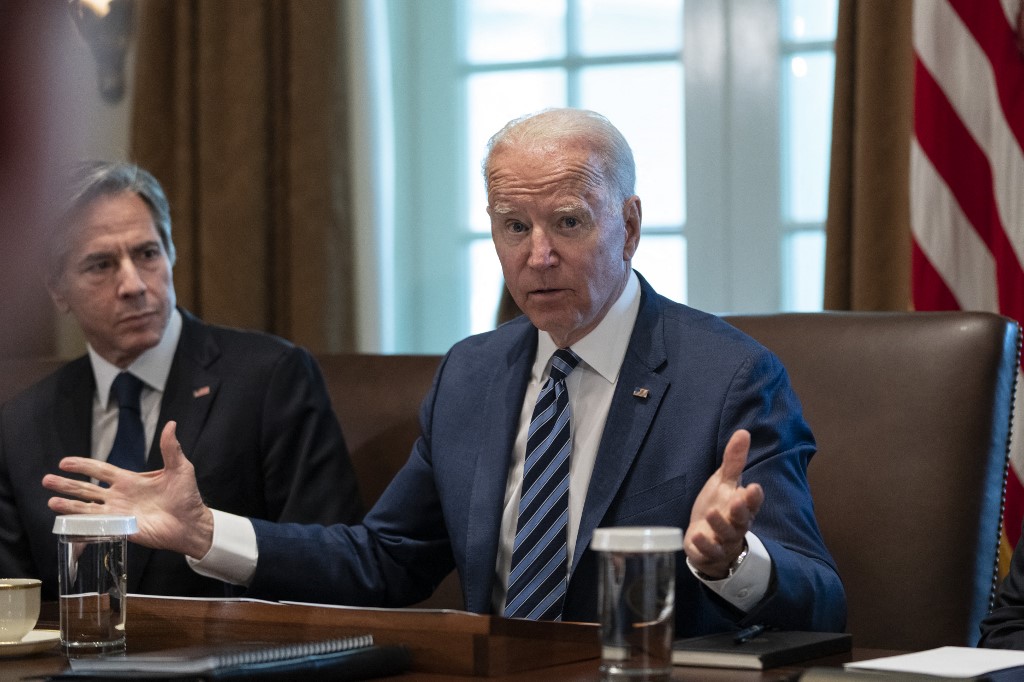

Raisi has stated that lifting the sanctions and ensuring economic recovery are the top priorities of his administration. Meanwhile, since his inauguration in January, US President Joe Biden has pledged to rejoin the nuclear deal and lift sanctions if Washington and Tehran can strike a deal to return to full compliance with the 2015 agreement.

The lack of progress in the nuclear negotiations and the ongoing tensions between Washington and Tehran are adding fuel to the intense crises in the Middle East

Since April, Iran and the six world powers that signed the original pact have been in talks to restore full compliance by both Iran and the US. The sixth round of negotiations was adjourned on 20 June. Expectations that an agreement would be reached under the Rouhani administration were proven too optimistic.

The parties are likely to go back to the negotiating table in the coming weeks, but it is not clear whether the Raisi administration will accept what has already been agreed upon, or start the process from scratch. What is clear, however, is that substantial disagreements persist. Senior American and Iranian officials have expressed frustration over the other side’s unwillingness to make the necessary “hard decisions”.

Maintaining leverage

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

On the US side, the Biden administration has called on Iran to return to full compliance with the 2015 nuclear pact and accept further negotiations aimed at limiting its missile development and regional influence. At the same time, Washington has offered to lift only the nuclear-related sanctions, while keeping sanctions related to accusations of human rights abuses and sponsoring terrorism.

In other words, the Biden administration seeks to maintain some leverage to pressure the Islamic Republic into changing its security and regional policies. To further heighten the pressure on Tehran, Secretary of State Antony Blinken has warned that the negotiation process cannot go on indefinitely, noting that the ball “remains in Iran’s court”.

On the Iranian side, after waiting a year to respond to Trump’s withdrawal, Tehran has increased uranium enrichment and stockpiling far beyond the deal’s limits. Equally important, it has limited the International Atomic Energy Agency’s access to its nuclear facilities. The significance of these developments, and many others, is twofold.

Firstly, the time it would take Iran to make a nuclear weapon - if it chose to do so - has been shortened. Tehran is getting closer to bomb-making capacity.

Secondly, the scientific knowledge that Iran is steadily gaining by building more advanced centrifuges and experimenting with higher levels of uranium enrichment cannot be erased. Robert Malley, the lead American negotiator in Vienna, warned that the Iranians are learning so much that it may be impossible to return to the nuclear deal in the near future.

Finally, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and other senior Iranian leaders have demanded that the Biden administration provide guarantees that it and future administrations can never walk away from a new agreement the way the Trump administration did. Given the significant pain Trump’s maximum pressure policy has inflicted on the Iranian economy, this concern is legitimate. But as the US president has the power to change the policy of his/her predecessor, Biden cannot provide such a guarantee.

Uncertain outcome

The outcome of the nuclear negotiations and the broader issue of US-Iran relations is highly uncertain. This raises two important, overlapping questions: What are the main lessons that regional powers can learn from these developments, and what can be done to prevent a further escalation of tensions between Washington and Tehran and a deeper deterioration of the Middle East security environment?

A close reading of statements made by senior Iranian and American officials, and the courses of action they have taken, or failed to take, offer some clues.

Firstly, Trump’s policy was aimed at exerting tremendous economic pressure on Iran that would force its leaders to reconsider their options and make key concessions on the nuclear programme, ballistic missiles and regional policy. The policy failed miserably.

Biden has been in office for eight months and, so far, there has been no change. Indeed, Iran has been under US sanctions since the 1979 revolution - more than four decades. Yet, despite occasional domestic crises and anti-government demonstrations, there are no signs that the religious/political establishment is losing control or about to collapse. Certainly, there is much to be desired, but the authorities remain firmly in charge.

Secondly, Iran - a nation of 80 million people with massive hydrocarbon deposits, an ancient civilisation, a strong national identity, and close ties with a number of its neighbours and other global powers - is a major regional force. Tehran has its fingers in almost every conflict in the Middle East and the surrounding region, including Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen.

The Islamic Republic can be part of the problem or part of the solution. Given its size, large population, and economic and military capabilities, Iran cannot be sidelined or isolated. Economic prosperity and political stability in Tehran would contribute to peace in the Middle East and around the world.

Thirdly, regional powers do not need to be bystanders. The lack of progress in the nuclear negotiations and the ongoing tensions between Washington and Tehran are adding fuel to the intense crises in the Middle East. Certainly, there are Arab-Persian and Sunni-Shia rifts, but they have long lived side by side and will continue to face similar challenges and mutual aspirations. Transnational challenges such as Covid-19, economic recovery, energy transition, and climate change require regional cooperation. There is no “national solution” to such crises.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.