Abdelaziz Bouteflika and Algeria: From the summit of power to the depths of hell

From his early career with the National Liberation Army during the 1950s to the presidential palace at the start of the new millennium, former Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who died on Friday aged 84, shaped not just the contemporary history of his country but also its political system - and an entire generation.

His last public appearance was on the evening of 2 April 2019, when, visibly ailing and dressed in a traditional djellaba robe, he was forced to resign under military duress amid massive popular protests by millions.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The image stands in sharp contrast with that of the impeccably turned-out president who had ruled the country for two decades, overpowering rivals within the system and even declaring in 1999 that: “I am the whole of Algeria. I am the embodiment of the Algerian people!”

His extraordinary life was marked by grandeur and excess, but ultimately ended under force. The source of that downfall can be traced to his lifeblood: the pursuit of power. Indeed, until he was forced to quit two years ago, regime insiders believed that only death would force him to go.

“Bouteflika was intent on maintaining power but not simply out of some authoritarian whim. It was his political philosophy, a vision inherited from post-revolutionary systems of governance,” one member of his inner circle said.

“A leader is not just a political leader. A leader is a father, and a father never abandons his family. Algeria was his family, and so was the Algerian people. To him, the palace of the presidency was his home, the home of Algeria’s ‘last great politician’.”

Bouteflika and 'destiny'

Bouteflika was born in Oujda, north-eastern Morocco, where his Algerian parents had emigrated in 1937. In the mid-1950s he joined the National Liberation Army and fought in the war of independence against colonial France.

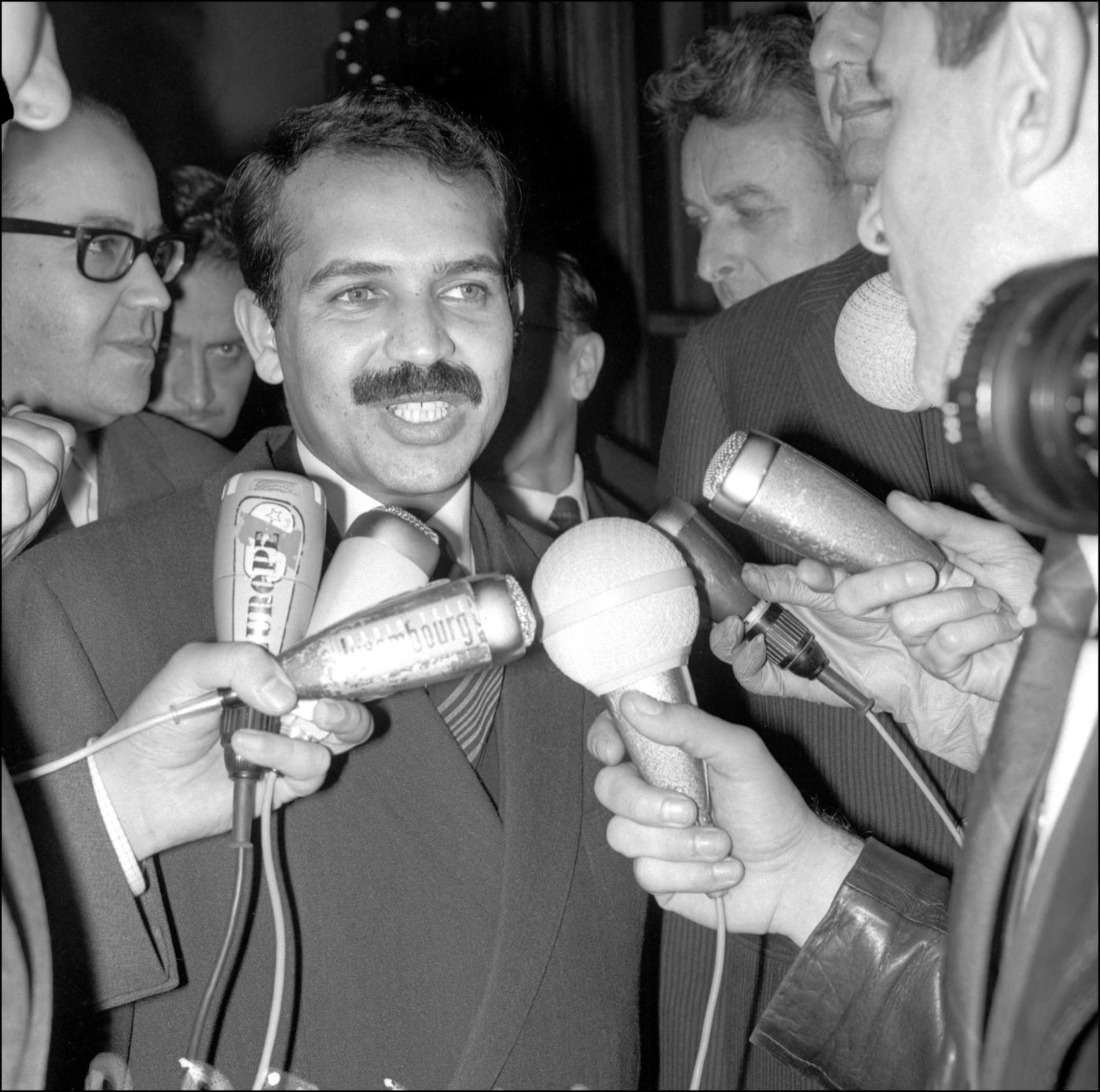

During the first post-independence administration in 1962, Bouteflika became Algeria's foreign minister. He benefitted from the coup, led by Houari Boumediene which unseated Ahmed Ben Bella, the country’s first president, in 1965.

Gradually, Bouteflika became a well-known face in diplomatic circles including serving as president of the UN General Assembly during the mid-1970s. At home, he increasingly became the protege of Boumediene, the spiritual father of the Algerian army and to whom Bouteflika had been close even before Algerian independence

So when Boumedeiene died from cancer in 1978, Bouteflika, seemingly driven by a particular sense of destiny, saw himself as the legitimate heir to the presidency.

But the army and the secret services had other ideas. Devastated by the loss of their supreme advisor, they had no intention of yielding power to the overly liberal Bouteflika, known for “his arrogance and poor understanding of domestic issues,” as former admiral Rachid Benyelles recalled in his memoirs.

Bouteflika never forgave the “system” for ousting him from his position as successor to his mentor or the accompanying betrayal.

Worse was to follow. In the early 1980s, Bouteflika was found guilty of squandering Algeria’s consular budget during his time as foreign minister. His name was splashed across the front page of the state-owned newspaper El Moudjahid (although most of its headlines would go on to extol his magnitude and political vision a few short years later).

Bouteflika knew the system had no pity for losers. He went into exile and was only eventually allowed to return to the country in 1989. By now Algeria was on the verge of the bloody civil war which was to dominate the 1990s and lead to the deaths of up to 200,000 Algerians.

For much of this period, Bouteflika had only a limited political role and instead bided his time. At one point in 1994, the army suggested that he become president in the wake of the assassination of incumbent Mohamed Boudiaf but he refused.

Driven by paranoia and a desire for revenge, Bouteflika finally became president in 1999, after he defeated incumbent Liamine Zeroual in elections.

“He was chased from it in 1979, and after twenty years in exile, he returned home,” one member of his inner circle said. “In his eyes, it was his right. His fate.”

Finally, President Bouteflika

The Algerian people were now reintroduced to Bouteflika’s signature banter, insolent blue eyes, and three-piece suits.

For some, he was a reassuring presence, reviving memories of the “glorious” years under Boumediene, when Algeria was the leader of the developing world – all in sharp contrast with the smouldering ruins of Algeria of the late 1990s.

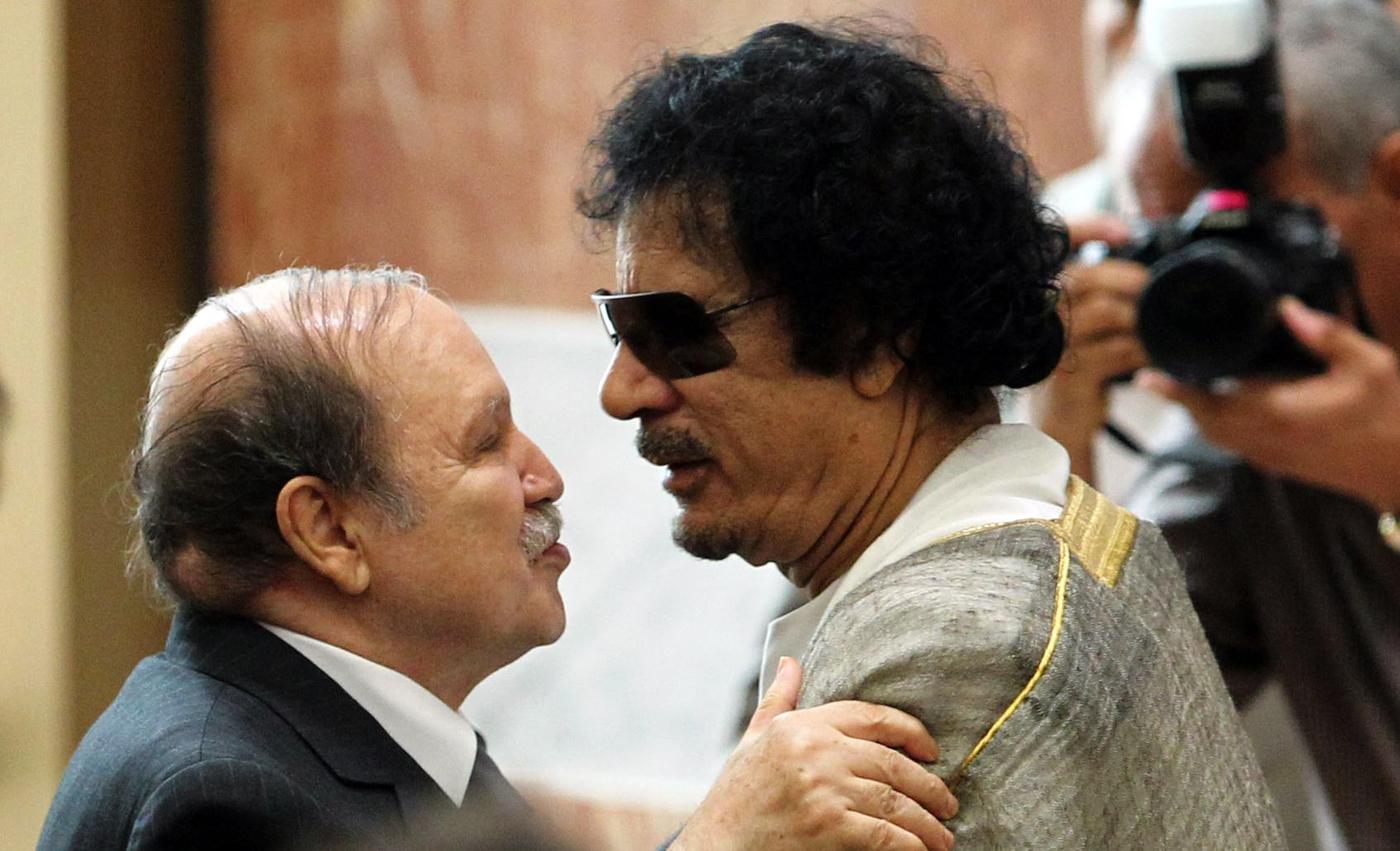

The illusion was credible, even among senior army officials who eventually co-opted Bouteflika, thereby erasing the disgrace of 1978. But illusions are wont to fizzle out, and this one was no exception - despite Bouteflika’s subsequent election victories in 2004, 2009, and 2014.

From the authorities’ crackdown on protesters in Kabylie in 2001 in what came to be called the “Black Spring,” and massive corruption scandals; to constitutional tampering to extend the president’s tenure in office and a series of economic fiascos, the demise of the regime of Bouteflika had already begun.

During the next two decades, Bouteflika introduced an acutely personal vision of power that reshaped all aspects of the regime’s political machinery, from the army to government administrations, including satellite organisations, such as business interest groups and the FLN.

The process was accelerated by the pluralisation of power, as seen through the interference of his younger brother, Said, in government decisions. Family ties and appointments could guarantee Bouteflika protection from the intrigues of government factions indirectly challenging his authority and projects.

“The Bouteflikas see enemies everywhere because there are enemies everywhere,” one former army officer commented.

“When a ruling family is in power for 20 years, you don’t only have friends. Remember Liamine Zeroual, president from 1994 to 1999, who said ‘this seat is the throne of hell,’ indicating his desk chair in the El Mouradia presidential palace.”

Elections and farce

In April 2013, Bouteflika suffered a stroke and was hospitalised in France for 80 days. By this stage even his most loyal supporters had to admit something was rotten in the regime of the Bouteflikas. The president’s mobility and speech were affected and he was rarely seen in public.

Power in Algeria was taking on increasingly surreal, even Kafkaesque, proportions.

The absurdities of his later years reached new heights during the presidential “campaign” of 2014 when the establishment announced the unthinkable: that its absent candidate would make a bid for a fourth term in office.

It wasn’t until election day on 17 April 2014 that Algeria and the rest of the world finally got a look at the presidential candidate. Wheeled in by the military physician who had signed his bill of health, and surrounded by his brothers, Bouteflika cast his vote.

While some viewed the masquerade as the ultimate whim of a once-powerful ruler who deserved to be allowed to die in peace, the Algerian people were profoundly shocked.

But the stakes were much higher than mere personal choice. It was in the interests of Bouteflika’s allies in the ruling party, as well as government officials, to keep the incapacitated president in office to pursue their predatory agenda.

The Bouteflika regime’s perennial attacks on the country’s checks and balances, whether institutional or informal, had completely obstructed the system.

Bouteflika won more than 80 percent of the vote amid opposition allegations of corruption. Algeria continued on its chaotic course, with a fourth presidential term defined by tensions including competing factions with the regime.

The crash from power

By now, the presidential image so cherished by Bouteflika had been destroyed and the regime undermined for good. During his final term, the president ruled from a healthcare facility far from Algiers, an isolated monarch debilitated by illness who muttered vague directives into his brother’s ear.

Moreover, the man who claimed to be the toppler of generals had allowed the army to emerge as the country’s main hub of power. One by one, the Bouteflika clan had laid the mines that would eventually blow them to pieces.

The humiliation of the regime’s bid for a fifth term in office triggered the final explosion.

In February 2019, former prime minister Abdelmalek Sellal announced Bouteflika's candidacy for a fifth term.

Within weeks Algerians, marshalled through social media, demonstrated. The rallies grew and continued to grow.

Inside the circles of power, the ranks were depleted by the resignation of several of Bouteflika's close allies from influential positions in politics and business. Assurances on 3 March that Bouteflika would not seek a full term were not enough to quell the rising tide.

With the army and other close allies against him, he withdrew on 11 March. The people he believed he led took to the streets and celebrated.

Abdelaziz Bouteflika wanted to be remembered as the father of the Algerian people. But he ended up alone, with all of eternity to ponder one of the Algerian proverbs he was so fond of: “Life is hard, but Algeria is harder.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.