2021's best books: MEE staff and writers' favourite reads of the year

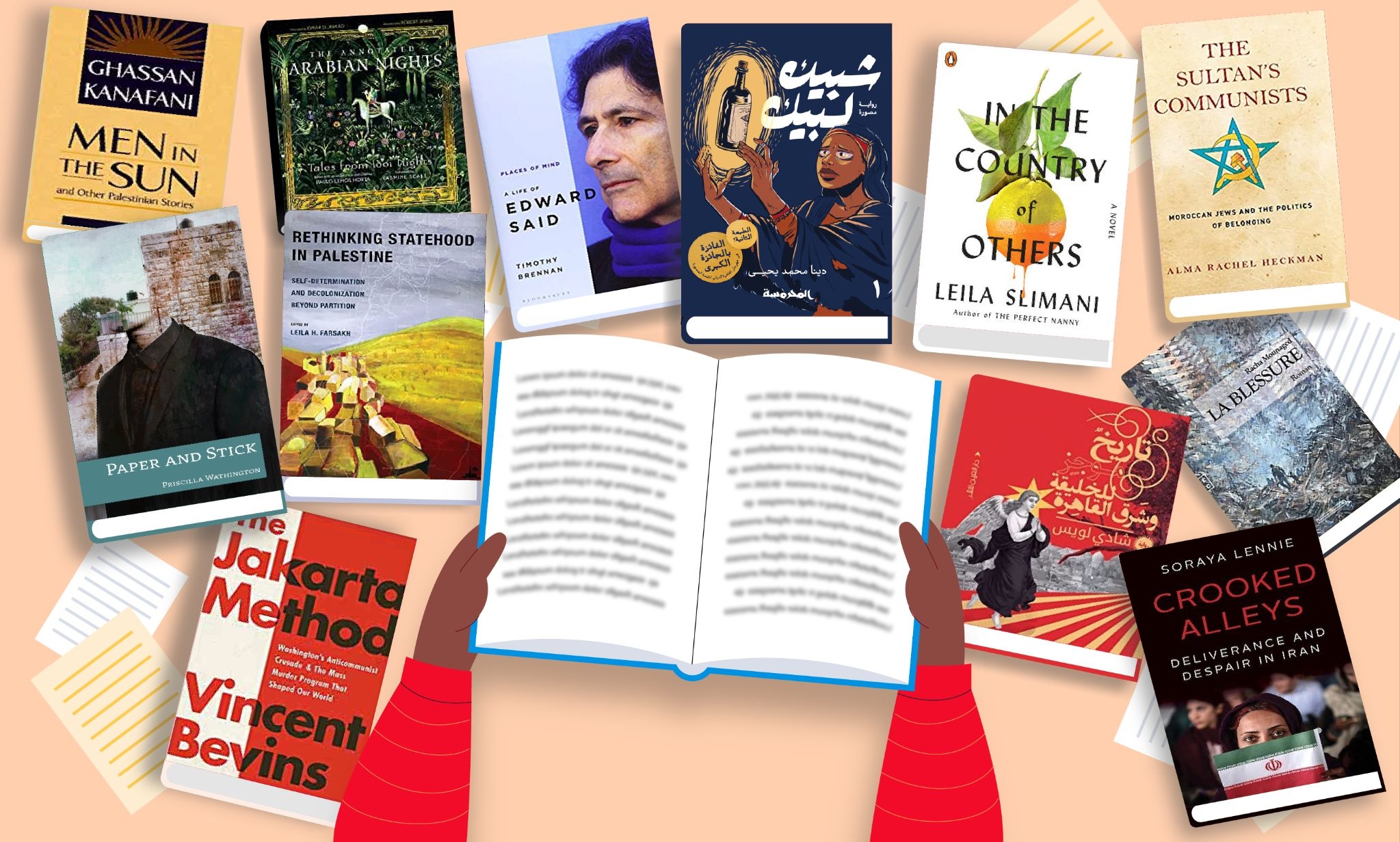

It comes as no surprise that books written by or about Palestinians dominate the list of favourite reads by Middle East Eye writers this year. Following the enforced Israeli evictions of Palestinian residents in the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah last May, and the ensuing violent crackdown on protesters, the events topped news agendas and led to a surge in interest in literature relating to the context of the conflict.

A new biography of Edward Said, whose work in postcolonial studies have become legendary, reveals that Said was not only a political activist and literary critic but may also have been an aspiring novelist. There's also Palestinian political analysis, memoir, poetry, and short stories in this year's picks. Although not included on the list, this year also saw the release of writer and activist Mohammed el-Kurd's searing new poetry collection, Rifqa, alongside numerous other selections of new Palestinian writing.

But our writers have been reading more broadly too, reflecting the diversity of their interests and backgrounds. We have books digging into the heritage of often-marginalised minorities, such as the Moroccan Jews in post-colonial Morocco, and Egyptian Copts in the 1980s.

While not all the titles on this list were published in their first editions this year - or even in the past 20 years as in the case of Ghassan Kanafani's novella and short story collection, Men in the Sun and Other Palestinian Stories, first published in 1978 - each no doubt offers a fresh reading of current events.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

1. Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said

By Timothy Brennan

Reading Edward Said's Orientalism has long been a rite of passage for any journalist working on the Middle East or aspiring anti-imperialist activist cutting their teeth. While the Palestinian academic deservedly takes his place among the pioneers of post-colonial theory, alongside Fanon and Cesaire, there is a tendency to turn him into a caricature not only among his critics but also his disciples.

For example, was a picture of the Jerusalem native throwing a rock in the direction of Israeli watchtowers on the Lebanon border an emotive act of resistance, a bit of fun that happened to be captured on camera, or perhaps both?

Few are as qualified to answer as Timothy Brennan, a former student of Said, who in Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said (Bloomsbury Publishing), supplements his own experience of the man with archival records and extensive interviews with those who knew him most intimately.

What emerges is a picture of a man driven by a lifelong quest to examine the genealogy of the power relations that brought about the plight of his people, but also someone who was unafraid to pillory student protesters interrupting his lectures or confront Zionist activists planning to gatecrash a meeting of Arab students.

In the age of identity politics, continued Israeli repression of Palestinian nationhood and widespread animosity towards refugees rooted in perceptions of the Muslim other, it is surprising it has taken so long for an authoritative biography of Said to emerge. Brennan's offering is a worthy first initiate.

Shafik Mandhai is a journalist and editor working on Middle East Eye's Discover section.

2. In the Country of Others

by Leila Slimani

French-Moroccan author Leila Slimani's third novel, In the Country of Others (Penguin Randomhouse), tells the story of Mathilde, a headstrong 20-year-old French woman from Alsace, who falls in love with Amine, a Moroccan soldier serving in the French army during World War Two.

Once the war ends, Mathilde moves to Morocco to live with Amine, and is forced to adjust to a country where she is a foreigner, dominated by her passionate but mercurial husband, and enmeshed in the crossfire of mounting tensions between the French colonists and the rising nationalist movement.

Along the way, a host of characters blossom in the story: Aicha, Amine and Mathilde's daughter, who faces discrimination from the French but is never accepted by her Moroccan brethren; Omar, Amine's rebellious younger brother, who joins the nationalists; Selma, Mathilde's teenage sister-in-law, who discovers her sexuality against the norms of family respectability; Dragan, a Jewish doctor from Hungary who becomes Amine and Mathilde's only friend.

Inspired by the romance of Slimani's own grandparents, and the first instalment in what is slated to be a trilogy, In the Country of Others candidly captures the challenges and complexity of lives lived in liminality, the changing times of modernisation in the postwar period, and the political upheaval of decolonisation.

Iman Sultan is a writer and journalist on politics and culture. She grew up in Philadelphia and now resides in Karachi, Pakistan.

3. The Sultan's Communists: Moroccan Jews and the Politics of Belonging

by Alma Rachel Heckman

One side of my family are communists, the other Moroccan Jews, so in my vanity I jumped at the chance to buy The Sultan's Communists: Moroccan Jews and the Politics of Belonging (Stanford University Press) when I saw it recommended on Twitter earlier this year.

What I like most about Alma Rachel Heckman's book is the complex picture it paints of both Morocco in the French colonial and independence eras and the Jewish community within it. She reveals a dizzying mosaic of political leanings, identities and allegiances where support - for the king, for Zionism, for Moroccanness, for socialism - can come in many different forms. That means there can be alliances and antagonisms that defy expectation (something observers of the Middle East and North Africa will of course be familiar with).

Heckman plots this through the lives of five Jewish Marxists who lived through the mass exodus of Jews from the kingdom, enduring growing suspicion of the community and authoritarian distrust of revolutionaries such as themselves.

In Cold War post-colonial Morocco, with the founding of Israel making waves across the region, these communist Jews had no chance of making a mark on their country. Instead, they have become national heroes who are heralded as examples of Muslim-Jewish tolerance.

Daniel Hilton is Middle East Eye's head of news.

4. The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales From 1001 Nights

translated by Yasmine Seale

In this strange moment when all of us feel off-balance, literature becomes a consolation. A good book channels a friendly presence and triggers a humanising dialogue. In an attempt to flavour our lives with the salt of the timeless, Tales From 1001 Nights (or Arabian Nights) stands out.

It’s a classic for a good reason as it embodies what storytelling does best, which is to elevate and reveal things previously unknown to ourselves.

Part entertainment, socio-political critique and pedagogical device, the tales re-imagine the spirit of Baghdad under the Abbasids, appropriating old Indian and Persian lore along the way. It's a collection of stories more than a defined canon and, due to its neither-here-nor-there-but-everywhere charm, carries a fluidity on authorship at which point its marvellous episodes become the comfort of a home.

This new annotated edition features Yasmine Seale's superb translation. She gives confidence to Shahrazad's voice, reintroducing a woman's wittiness, ingenuity, and her "survival by cliffhanger" to contemporary readers.

Augmented with mesmerising reproductions of paintings, other illustrations and immersive essays, this book, which turns the clock backwards, is a work of art. It historicises and re-contextualises cultural sources and literary traditions, including how the tales fed a European Orientalist fantasy.

After each page, The Annotated Arabian Nights (WW Norton) revives (my, our) childhood memories and a time when the supernatural and wonder were as essential to one's existence as breathing.

Farah Abdessamad is a French-Tunisian essayist and critic who was based in the Middle East for most of the 2010s, in peace yet mostly in war.

5. Crooked Alleys: Deliverance and Despair in Iran

by Soraya Lennie

When you want to know more about a country, you can't beat hearing from the people themselves, and that is precisely what Soraya Lennie has achieved with her remarkable Crooked Alleys: Deliverance and Despair in Iran, published this summer by Hurst.

Lennie weaves the voices of Iranians into a narrative tapestry of life inside the pressure cooker that is Iran. Stories beyond the headlines of those hit hardest by events in the wake of the 1979 revolution, through to the collapse of the nuclear deal and the calamitous re-imposition of sanctions, paint a picture of global demands and domestic misgovernance and how they frustrate daily life.

An Australian-Iranian investigative journalist based for many years in Tehran, Lennie illustrates an Iran at yet another turning point in its history, from attempting to shake off the legacy of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's polarising populism, through a glimmer of reform, to the surge in support for hardliners as the Covid-19 pandemic hit.

It is a tale of resilience in the face of hopes dashed and ambitions thwarted, and Lennie's deft writing offers context and nuance to the understanding of a country too frequently out of reach for many of us. Despite the weight of the subject, Lennie's light touch makes Crooked Alleys an invaluable, accessible - and very necessary - guide to today's Iran.

James Brownsell is a sub-editor at Middle East Eye. He was formerly managing editor of The New Arab and Europe editor at Al Jazeera English.

6. Rethinking Statehood in Palestine: Self-Determination and Decolonization Beyond Partition

Edited by Leila H Farsakh

From the Balfour Declaration to the UN Partition Plan to the Oslo Accords, Palestine has resisted fragmentation, proving time and again to be indivisible, from the river to the sea. Meanwhile, the Palestinian yearning for self-determination remains unquenched. In this present context, as partition and occupation turn into long-term annexation while cementing apartheid, decolonial scholars today are looking at alternative ways to achieve sovereignty, shifting their analysis from "statehood" to "nation".

Rethinking Statehood in Palestine: Self-Determination and Decolonization Beyond Partition, edited by Leila Farsakh, features an outstanding collection of essays by a new generation of primarily Palestinian scholars, who propose a way out of the impasse of seeking statehood, the relatively modern western/imperial concept, privileging instead the land-based concept of nation, which prioritises the people's lived experiences.

The essays offer renewed hope, as they provide innovative ways out of the two-state "solution," which Israel is openly determined to block, while exploring the issues of citizenship and sovereignty within the context of decolonisation.

Bonus: the book is available for free download from the University of California’s Open Access site.

Nada Elia teaches in the American Cultural Studies programme at Western Washington University, and is currently completing a book on Palestinian diaspora activism.

7. The Book of Travels,

by Hanna Diyab

In late 1708, Hanna Diyab was tricked out of a job and forced to leave France. If we believe the gossip relayed in his memoir, it was by a jealous Antoine Galland (the first European to translate The 1,001 Nights), who recognised the Syrian teen's genius and could not bear the competition.

Scholars knew, from Galland's diaries, that Diyab was the source of "Aladdin," "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves," and other stories. But it was only in the 1990s that Diyab's own coming-of-age memoir was discovered at the Vatican Library.

Diyab's memoir, The Book of Travels (NYU Press), opens when he was a young Maronite aiming to join a monastery, but, when he sees himself in a dumpy monk's frock, he knows this isn't for him. He meets a treasure-seeker of the French empire and agrees to join him as fixer and translator, travelling with him to Versaille. There, he meets Louis XIV and Galland.

The man who gifted Galland some of the greatest Nights-adjacent stories also had a genius for observing stark inequalities in France and elsewhere. Diyab does not seem to care that French literati sidelined and ignored him; nonetheless, it is a joy to celebrate his work in Elias Muhanna's vibrant translation.

M Lynx Qualey is an editor, occasional translator, and critic who founded the 'ArabLit' website (www.arablit.org), which won a 2017 London Book Fair prize. She also publishes ArabLit Quarterly magazine and is co-host of the literature-focused BULAQ podcast.

8. Paper and Stick

by Priscilla Wathington

The autumn of 2021 saw the publication of Priscilla Wathington's debut collection, Paper and Stick (Tram Editions, Colorado Texas). Its beautiful cover art is by artist Manal Deeb, who is, like Wathington, a Palestinian American.

A former managing editor for Defense for Children International - Palestine, an independent child-rights organisation dedicated to defending and promoting the rights of children living in Occupied Palestine, Wathington looks to her work for creative inspiration.

Her poems are haunting, reminding us of the ways in which the occupation destroys and erodes the notion of a normal childhood.

The poems, in both what they say and what they erase, serve as documentation of the terror endured by Palestinian children in the West Bank and Gaza: "what happened to me was a mouth | white Kia pulled/ over |," she writes in White Kia, "inside a wavecurl/ a common gnaw | kidnapped us without saying a word/ my ribs/prayer in its cavity".

In Deadline Extended, she writes about children who are kept in military prisons: "they tied me to that chair every time/ 15 times, but I never/ only to find the muscle is wood/ air that was coming into the cell".

Her voice is clear and powerful, and above all, it echoes with compassion.

Susan Muaddi Darraj is the author of A Curious Land, which won the American Book Award, and the "Farah Rocks" children's book series.

9. Shubeik Lubeik

by Deena Mohamed

In a parallel Egypt, wishes are bought and sold as one of the world's most precious commodities. The more expensive the wish, the more powerful, a premise around which comic artist Deena Mohamed has spun a graphic novel trilogy that is at once intimate and expansive, carefully constructed and insightful.

With the release of the third and final instalment this year, Shubeik Lubeik has come together as one of the most imaginative works of Egyptian fiction in recent years.

The trilogy follows three first-grade wishes and the three lives they change: Aziza, Nour, and Shokry. Each character and their surrounding world is vivid and unique, drawn with an overarching empathy that drives the stories forward.

More than anything, Shubeik Lubeik is surprising. Under the cover of a light-hearted graphic trilogy (look, well-drawn comics! With distinctly Egyptian motifs! Magical realism at a street kiosk!), Mohamed guides us by the hand into the unexpected.

Each story - progressively deeper and more complex as we watch Mohamed grow as a comic artist - grapples with issues of faith, class, colonial legacies, mental health, freedom of choice, political violence, and injustice, so cleverly that the end of every book is both cathartic and charming.

Bahira Amin is a freelance journalist and producer based in Cairo.

10. A brief history of genesis and East Cairo

by Shady Lewis

Over a span of three novels, the London-based psychologist turned novelist Shady Lewis has emerged as an astute, perceptive chronicler of Coptic Christian life, a key facet of Egyptian society that remains under-represented in both literature and cinema.

Set over the course of a single day in the 80s, Lewis follows a battered Coptic mother attempting in vain to flee her abusive husband with her young guileless son.

A Brief History (Dar al-Ein) is a rich study of the different forms of violence - institutional, familial, political - inherent in the Egyptian experience and how it is passed on from one generation to another. It is an intricately structured novel that combines personal recollections, the forgotten account of the 1986 Egyptian conscripts riot, and the obscure history of the Protestant mission in Egypt. The story brilliantly contextualises the marginalised narrative of Egypt's largest minority group within the incessantly modified history of the country.

Bleak and unsparing in its depiction of the reality of its lower middle-class characters, Lewis's most audacious feat is in his observant exploration of the relationship between the authoritarianism of the Mubarak regime and the economic demise of the middle class, with the apathy of the church hierarchy towards its parishioners.

It's also one of the rare, great Egyptian novels about the act of walking, offering a rich panorama of the fading Cairo of the 80s, a once wondrous city spiralling into self-destruction and steady deformation.

Joseph Fahim is an Egyptian film critic and programmer. He co-authored various books on Arab cinema and has curated film programmes in Europe, the US and the Middle East.

11. Sambac Beneath Unlikely Skies

by Heba Hayek

Sambac Beneath Unlikely Skies by Heba Hayek, published this year by the proudly political and anti-racist Hajar Press, was a book I devoured in a single sitting.

The narrator of this not-quite autobiographical, not-quite fictional memoir takes us on a journey through a childhood in Gaza.

There is her tragic, radical awakening at the murder of Muhammad al-Durra; her near-death experience of Israeli bombs on her school; the momentary elation at the emptying of settlements from the Gaza Strip in 2005, and time dilating with the escalating wars of 2008 and 2014.

Between these grand political scenes are the tender moments of growing up: of the love of aunts and neighbours, childish love letters and cousins at play.

Hayek paints a delicate portrait of the women of Gaza and captures childhood experiences shared by the Palestinian generation who today lead the struggle against Zionism and occupation.

Ali Al-Jamri is a poet, translator and teacher based in Manchester. He edited Between Two Islands, published by No Disclaimers.

12. Conditional Citizens

by Laila Lalami

In Conditional Citizens (Penguin Random House), Moroccan-born writer Laila Lalami takes the reader on a fascinating intellectual exploration into what it meant to her to become an American citizen. The Pulitzer Prize finalist intimately speaks in her fifth book of her life experiences, of the politics of the country she was born into and of the one that later became her home. She eloquently describes the complexity of her emotions and the events that shaped her views and her identity while exploring how citizenship and equality are shaped by race, religion, gender and class.

The book is rich with personal anecdotes that Lalami generously shares about herself, producing what is essentially, for those who are familiar with her work, a culmination of thoughts and observations that she has penned over the years in her columns.

The book speaks of the racism that is present in all aspects of American life, from the post 9/11 treatment of Muslims to the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. It also draws from past history to explain that society is constructed so that White people, and men in particular, are kept in power, while everyone else never fully benefits from the same rights as citizens.

Lalami describes how privilege in the United States is preserved through oppression, using recent and past history to illustrate her argument in an attempt to defend the idea that if citizens are indeed born equal, there is still so much to do in order to ensure that they remain as such until they die.

Aida Alami is a roaming freelance Moroccan reporter whose work was featured in The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the BBC, among others.

13. The Jakarta Method

by Vincent Bevins

With The Jakarta Method, the American journalist Vincent Bevins has written a jaw-dropping book that centres on the Indonesian genocide of the 60s but which zooms out to tell the story of anti-communist violence and propaganda carried out around the world throughout the Cold War era.

What happened in Indonesia is awful enough: more than a million people killed, with the help of US and British intelligence agencies, resulting in a right-wing dictatorship that served western needs. Bevins interviews survivors and draws on archive material to bring the story to light. What is most affecting is the way in which the earnest hope that young leftists had for a post-imperial Indonesia is exterminated by an army regime and a United States intent on connecting the desire for a better world in the global south to the dark hand of Moscow.

What happened in Indonesia became a blueprint for US-sponsored anti-left violence and repression across the globe. It became known, then, as the "Jakarta method". People's movements from Latin America to the Middle East were crushed and replaced by military juntas that served US corporate interests. It is no exaggeration to say that this has shaped our world, creating or accelerating many of the most serious problems we face today, including the climate crisis and the unravelling of democracy.

In the Middle East, the active repression of left-wing movements opened up a space that was filled by groups like al-Qaeda. With what had been the most visible viable alternatives to capitalism and imperialism gone, militant Islamist groups, often funded and supported by the US, emerged.

An honourable mention must also go this year to the newly published The Dawn of Everything, a mighty new history of humanity that shows how depictions of our remote ancestors as primitive and childlike "emerged in the 18th century as a reaction to indigenous critiques of European society". Archaeologist David Wengrow and the late anthropologist David Graeber break apart all the well-seated intellectual beliefs of the West and, in doing so, allow the reader to imagine a radically different future. It includes within it rich explorations of a number of Middle Eastern cultures.

Oscar Rickett is a journalist who has written and worked for Middle East Eye, VICE, The Guardian, openDemocracy, the BBC, Channel 4, Africa Confidential and various others.

14. La Blessure

by Racha Mounaged

Although this debut novel by Belgo-Lebanese writer Racha Mounaged was published last year, the events it recounts are still so pertinent it calls to be read against recent political developments in Lebanon.

In La Blessure (perhaps best translated as The Wound, published by Editions Complicites), we are introduced to a series of flashbacks set during 1990s Beirut through the lens of a vulnerable teenage boy, Jad. Raised in a broken household with financial problems and the madness of the war waging around him, he dreams to escape. Just like Jad in the novel, for so many Lebanese today education is the only way out. For this, and many other parallels, the novel remains just as relevant today as it was last summer when it was first released.

Despite the hardships, Jad lives moments of joy: a sole friendship with a fisherman by the sea, dressing up for his mother's birthday, the first feelings of attachment for a girl. Childhood is there, intact, with its sensuality and its promises. Yet the trauma of the war and the damage of the post-war reconstruction period is never far from sight. Fast forward to the end and we learn that Jad has been selected to represent Lebanon in an international history competition in Athens.

Following a final burst of fighting, the competition is cancelled. The sensible and precocious Jad collapses into a raging fury and stabs his bully Raphael, as we learn in one of the earliest flashbacks presented in the novel. Ironically, the weapon he uses belongs to the rich and privileged: an oyster knife. Unrecoverable class injustice married with the emotional trauma of his parent's divorce result in the wound that he inflicts across his adversary.

It is through his painful circumstances that we can empathise with Jad's act from the start. To read La Blessure today is ultimately an act of empathy. We are called to empathise with Jad, but also with the Lebanese and all the misery their government has subjected them to, especially throughout this past year, where once again justice has not been met, and the criminal politicians have bought another year of impunity.

AJ Naddaff is a multimedia journalist and translator pursuing a MA in Arabic literature at the American University of Beirut.

15. Men in the Sun and Other Palestinian Stories

by Ghassan Kanafani

Delving even further back, and, again, more relevant than ever, is this next read. It was 17 years ago that I first read Men in the Sun (Heinemann, 1978) yet it's been seared into my mind ever since.

While definitely not a new release, this novella, published in Arabic in 1962 by late Palestinian writer and political activist Ghassan Kanafani and which I read again this year, is more relevant than ever for the way it captures the trauma of displacement and the precarity and hardship of Palestinian refugee life.

Kanafani himself became displaced at the age of 12, when the state of Israel was created in 1948, and lived in exile in various Arab countries.

In the novella, Abu Qais, Assad and Marwan, three Palestinians of different generations, are exiled in the Iraqi city of Basra, living in miserable conditions. To build a better future, they embark on a hazardous and expensive journey across the desert to Kuwait.

They happen upon Abu Khaizuran, a smuggler who agrees to drive them in his water tanker across the border. But there is one condition: when they reach customs the men will have to hide in the empty and rusty tank, with the cover shut, beneath the scorching August sun. They only have to hide "for five or seven minutes," Abu Khaizuran reassures them.

The men, desperate to reach Kuwait, agree. The lorry "was carrying them along the road, together with their dreams, their families, their hopes and ambitions, their misery and despair, their strength and weakness, their past and future," Kanafani writes.

At the frontier, the smuggler is held up by border officials. Seven minutes pass, but he makes it to Kuwait.

"Why didn't you bang the sides of the tank? Why? Why? Why?" the driver's voice echoes in the desert once he opens the tank's lid. Just as it will echo in your mind after reading this book.

Vittoria Volgare Detaille is a journalist and Arabic translator based between Belgium and Kuwait. She is a consultant for various UN agencies and has worked with the Italian Press Agency ANSA.

16. Innocent Until Proven Muslim: Islamophobia, the War on Terror, and the Muslim Experience Since 9/11

by Maha Hilal

This year is 20 years since the events of September 11 2001. Journalists, activists and academics marked the event earlier this year, poring over the infinite details of a day that changed America and the world.

But this year also marked 20 years since the start of the US-led "War on Terror" that began following 9/11. Close to a million people have been killed and tens of millions of others displaced in a war that shows no sign of any end. Predictably, not enough has been written about this war; the lives it has destroyed and the prejudice it has sown, and the precedent it has set for illiberal regimes to clamp down on dissent.

Maha Hilal's book, Innocent Until Proven Muslim: Islamophobia, The War on Terror, And the Muslim Experience Since 9/11, is therefore a timely intervention. In it, Hilal details how the American war machine used the discursive power of the state and the media to portray itself as "guarding freedom and democracy" even as it invaded countries, surveilled its own citizens, exercised torture and extra-judicial killings around the world.

Examining speeches from Bush to Trump, policy documents and paying close attention to language, Hilal painstakingly dissects the many ways in which Muslims have been vilified over the past 20 years. The dehumanisation of Muslims has therefore given impetus for egregious foreign policy to exist without much public scrutiny.

Hilal's book veers into the often-ignored and largely erased discussion of American Muslim complicity in making the War on Terror more palatable at home. The War on Terror killed but it also left some Muslims resenting themselves. For this alone, the book is a must read.

Azad Essa is a senior reporter for Middle East Eye based in NYC.

Editor's note (3/12/2021): Conditional Citizens is Laila Lalami's fifth book and not fourth as previously stated

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.