'How will it end?': Lebanese artists and the Beirut blast

When multidisciplinary artist Abed al-Kadiri moved from Beirut to Paris a year ago, the first thing he noticed was the migration of the birds. For him, it was a reminder of the situation for many living inside Lebanon. A bit like the birds, “the Lebanese people are leaving the country on a daily basis. The number of fellow artists and people of my generation who left is scary, shocking,” the 37-year-old tells Middle East Eye. In It’s Not Black or White, Kadiri uses the image of the bird to symbolise the ideas of freedom and hope but also the dark reality of migration.

Kadiri's work was produced specifically for an exhibition by the Boghossian Foundation in the Belgian capital Brussels called How Will It End? Before it ended on 6 February, the exhibition showcased works by 43 Lebanese artists living in the country and abroad. Through their art they are trying to come to grips with the ongoing social and economic crisis that has plunged Lebanon into a figurative and literal darkness.

Many of the paintings, sculptures and videos on show were produced after the Beirut blast in August 2020, which devastated the city, leaving more than 200 dead and 300,000 homeless. Artists were among the victims as well. Some died, others lost their works, homes or studios. Confronted with this catastrophe, many have captured the moment of the blast and the devastation that followed. (Thibault De Schepper)

Last December, on the opening night, Kadiri confronted visitors with a black mural made of 35 canvases covered in charcoal and invited them to work on it. On the left of the mural there was a red circle that has become his signature, “symbolising the sun, but also the moon, the explosion and the wounds”, the artist says. More than 100 people worked on the charcoal surface in what Kadiri calls the "erasing process". It was also the first time the artist had engaged with the public. Using an eraser, the audience was invited to "create through destruction".

“I gave the people a democratic point of view, the ability to change or correct all the mistakes we have made as Lebanese people or humans in creating our history,” Kadiri says. The more people erased, the more the underlying whiteness of the canvas together with the birds, which the artist had placed under the charcoal, became apparent. “It’s been over a year since the blast, yet we still feel deprived of the chance to fix and mend Lebanon's path. Blackness is still pervasive,” the artist explains.

According to Kadiri, in Lebanon, black is no longer a metaphor, but a reality. “Those who remain, spiral in darkness. The dream, if any, has become simply to leave. Yet, in leaving, we do not feel liberated. We become like seagulls wandering suspended between the two blues.” (Thibault De Schepper)

When asked about Beirut, the artist Ayman Baalbaki says he doesn’t know where to start: “Shall I go back to the city of Beirut that was buried seven times throughout history under the rubble of earthquakes and later under the ruins of wars?”

Baalbaki was born in 1975 at the start of Lebanon’s 15-year-long civil war and grew up witnessing bombings and destruction, later living through Israel’s 2006 invasion. The memory of these events is visible in Baalbaki’s work. The artist is known for his expressive portrayals of fighters wearing keffiyehs or gas masks and also for paintings of buildings destroyed as a result of conflicts.

In the 2021 artwork above called Untitled, Baalbaki immortalises the August 2020 blast, not shying away from the devastation it causes or the resilience displayed by the city’s residents in its aftermath. He explains: “Beirut is a capital built, throughout the ages, around its harbour. Soon after the August explosion, which destroyed the city's heart, life returned to normal. The city dusted off its ruins and added a new wound to its shattered body.” (Courtesy of the Saleh Barakat Gallery, Beirut)

Video and visual artist Ali Cherri brings “dead objects” back to life. The destruction and the loss of Beirut’s traditional homes and the importance of archaeological objects in the construction of historical narratives are central to his latest works. Staring at a Thousand Splendid Suns and Life After Life, two sculptures completed in 2021, are a reference to the damaged or disfigured bodies caused by the blast. The first is sculpted from a wooden mask dating back to the period between the 4th and 7th century CE. The second is made of glazed stoneware moulding and ocular prostheses (artificial eyes).

“The starting point of the sculptures is an old broken fragmented object. I usually collect them from auction sales and then I add the missing parts until they are complete again,” Cherri, who splits his time between Paris and Beirut, explains. “But we are left wondering if this return is a return of the human to the bodily, or simply a return of the object-as-monster… Our confrontation with their gaze is an intimate encounter, revealing the nature of these composite creatures: they are soulful entities which can affect and be affected." (Thibault De Schepper)

Mixed media artist Chafa Ghaddar spent a lot of time during the past two years in her garden in Dubai where she has followed Lebanon’s many tragedies from a distance. “Witnessing the plants grow was a constant. Everything was stagnating or massively violently changing, like the way it was happening in Beirut, and these plants and cacti gave me not only a sense of relief but stability,” the artist says.

This is when she started Cacti in a Daydream, a series of colourful frescoes dedicated to the plants in her garden. “The artworks are frescoes on wood but the visual on them is not structured like they usually are in frescoes. It was very liberating; it needed to breathe out the intensity of the past two years and to be received as a sort of fresh air,” Ghaddar adds.

She chose the fresco because it gives the promise of durability and the strength of surfaces. At the same time, she says that despite the durability of fresco, it is a medium that after centuries will eventually decay. The ambiguity of fresco seems to echo the landscape of Beirut and what the city goes through. “It keeps growing and destroying itself, it keeps changing in extreme directions. Maybe these frescoes suggest an act of faith, hope in a way something could be rearranged in this promise of durability, in this reality of decay. That something could possibly stand still, resist with resilience and fragility, vulnerability and strength at the same time.” (Thibault De Schepper)

View from home #2 is part of a photographic series by Jeanne and Moreau, a pseudonym for artists Lara Tabet and Randa Mirza. Working together since 2018, the photographers used binoculars to portray Beirut from the window of their home overlooking the port. The picture on the left depicts a person relaxing on a terrace during confinement in the spring of 2020, during the pandemic.

On the right, we see a different terrace of the same building immediately after the explosion, so as to highlight Beirut's pattern of construction and destruction. “We chose this particular work because it embodies the state of rupture in our space and time continuum and the cyclical violence that occurs in Lebanon,” the artists tell MEE. The photographers also explain that the artwork shows “the cognitive dissonance that occurs when our systems of belief are constantly challenged and fragilised by acute traumatic events.” (Courtesy of the artists and Galerie Tanit, Beirut)

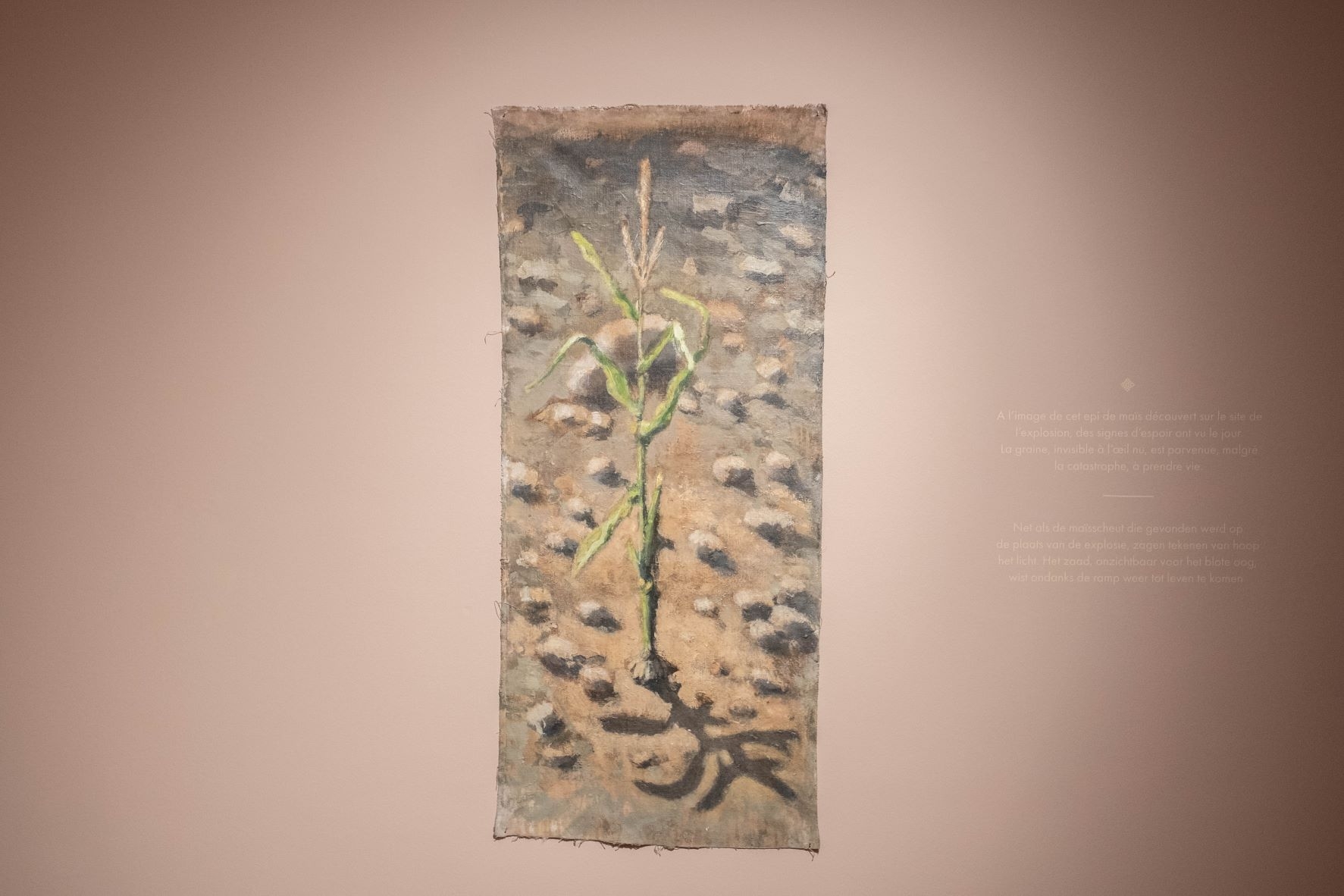

A sign of hope and life amid destruction is the message painter Omar Fakhoury wants to deliver with Corn Plant. A direct reaction to the explosion, the 2021 artwork has a corn shoot as the main subject.

The silos destroyed by the blast contained essential grain reserves including corn, wheat and barley. The structure served as storage for about 85 percent of Lebanon's imported cereals. “I stopped working right after the port explosion and after eight months I wanted to start from somewhere, so I got a permit to visit the site of the explosion in person,” the artist says. He says he was walking when he saw “a solitary corn plant in the midst of the ruins.” Despite the tragedy, the seed came to life. “I went back to the studio and painted it,” Fakhoury says. (Thibault De Schepper)

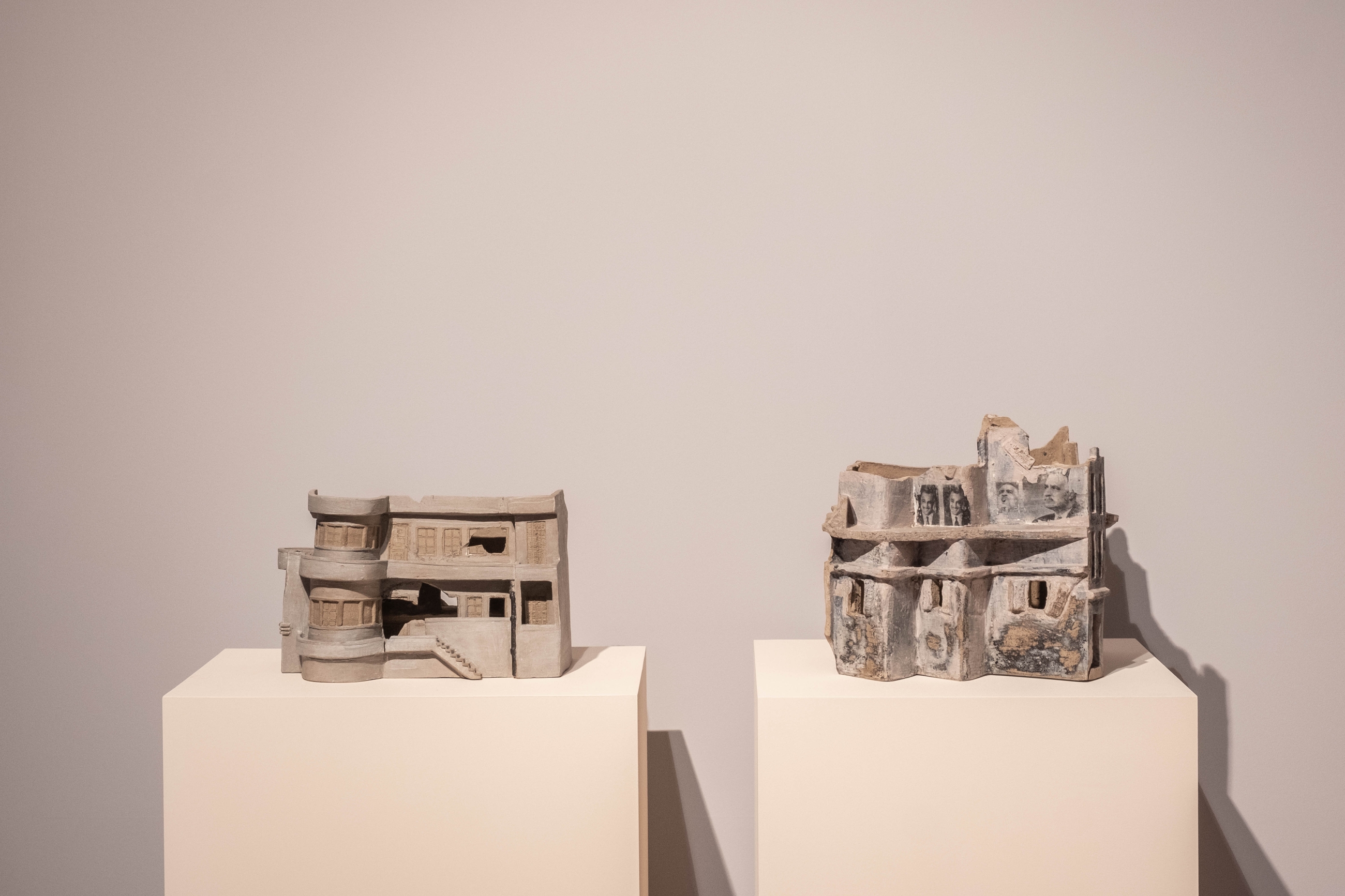

The recurrent theme of destruction is not only related to the port explosion. It has been widely tackled by Lebanese artists over the past decades. Samar Mogharbel’s work deals with memory, of the war but also of the heritage buildings lost to urban development. In Watwat I (left) and Hamra (right), the ceramic artist brings back to life buildings the way she remembered them as a child. These two houses are part of a 2014 series made mainly of stoneware clay, but porcelain as well.

She says: “It all started when I was looking at old photos of when I was five or six years old. I found a picture of me and my twin sister standing in front of the house we lived in for nineteen years. It was destroyed and a new building replaced it. I wanted to reconstruct our house in 3D to see it again, with its dimensions.”

Mogharbel says that with the constant construction in Beirut, much of the city’s unique old houses, with arcades and high ceilings, have been lost. “All the memories of simple people are gone with them,” the artist says. She has therefore set about recreating them in miniature. In Hamra - named after a west Beirut neighbourhood - Mogharbel recreated the now demolished three-storey building that was in front of her childhood house. “Posters of late Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser…were still glued on the walls.”

Watwat - the name of another neighbourhood in the east of the capital - is the reproduction of a damaged building still present in Beirut. When Mogharbel recreated it, it was very difficult for her to disfigure it. “I had to use a hammer - it was as if I was destroying the original building.” (Thibault De Schepper)

Multimedia artist, watch and jewellery designer Pierre Koukjian is always eager to start a debate through his art. The Geneva-based artist was born in Beirut in 1962 and left the country when the civil war broke out.

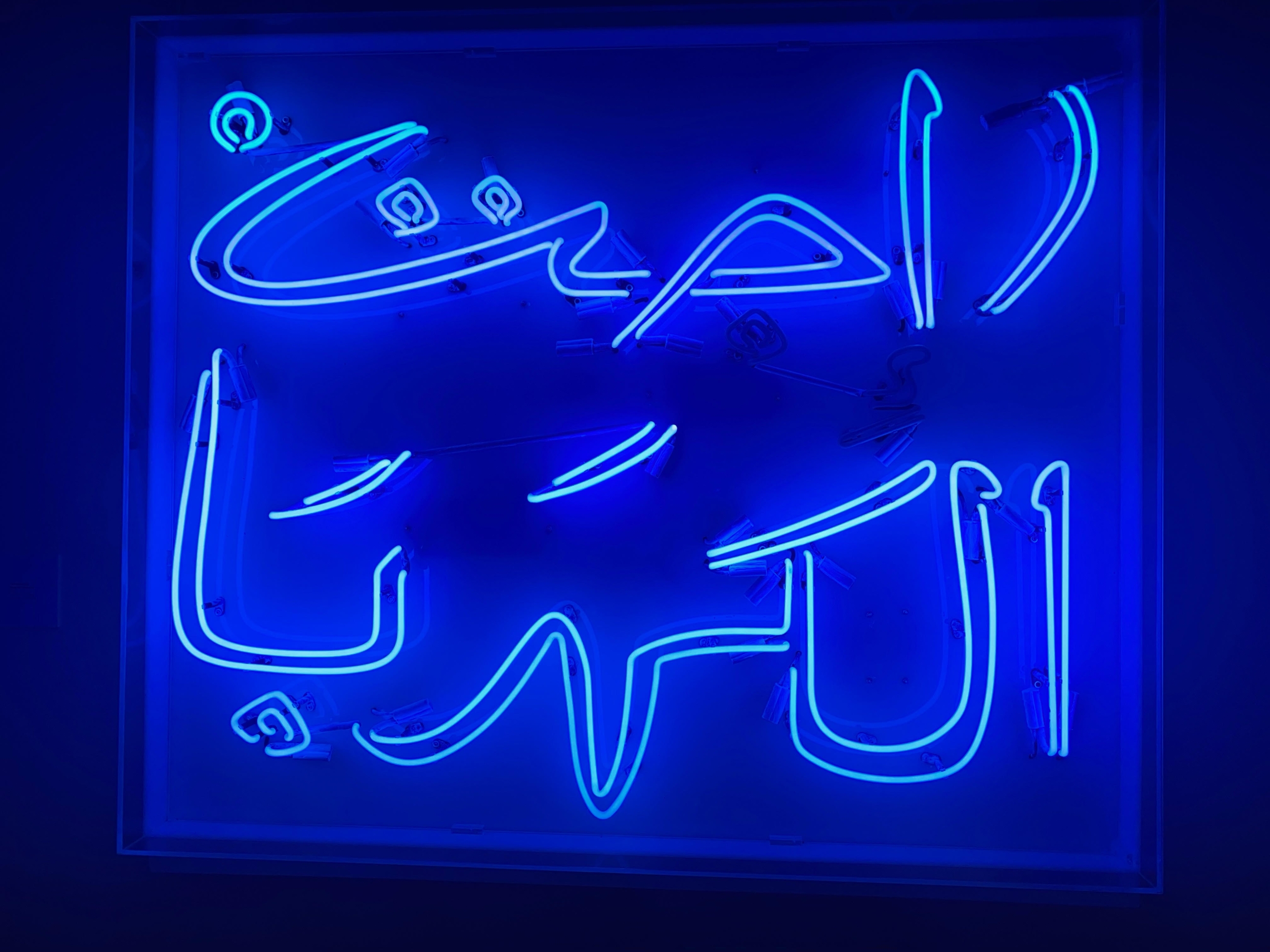

With the neon blue piece Power On/Power Off he tackles with satire the poor state of infrastructure in various Arab countries. “I completed this work during the Arab Spring (2012)... The work is also inspired by the continuous problem of power cuts in Lebanon,” Koukjian says. “Electricity also means power.” (Vittoria Volgare Detaille)

A bright blue neon light flashes on and off to alternate the two sentences in Koukjian's work, Eejet Al Kahraba (pictured above), Raheet Al Kahraba (pictured here), meaning "Electricity On, Electricity Off" in Lebanese Arabic. Using the richness and versatility of the Arabic language, Koukjiean wants to send the message that just as the electricity and the neon lights, power is also volatile and fragile; it comes and goes. “It can go from one extreme to the other,” the artist says. (Vittoria Volgare Detaille)

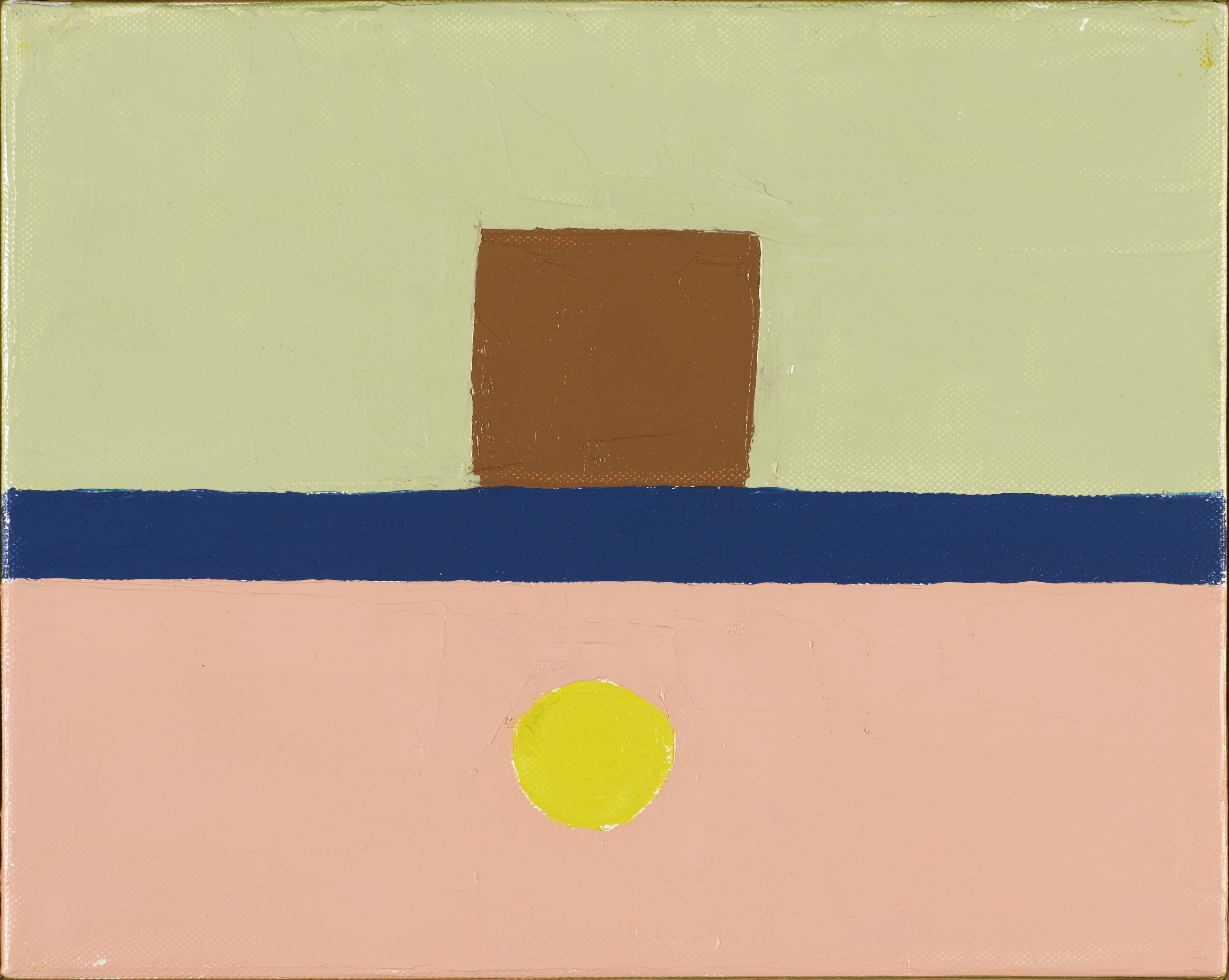

“All adults should definitely draw,” visual artist Etel Adnan told the exhibit curators before passing away on 14 November 2021. She said that it is as if art was a way to escape tragedy. The artist said she had “deep love for life, the phenomenon of life”.

A celebrated and award-winning poet, essayist, journalist and author, Adnan is also known for her abstract and bright colourful oil paintings. Made of simple lines, they are a celebration of nature but also of the world and humanity. She continued producing art until her death at the age of 96. Part of the 2010 Untitled series, the two artworks are landscape panoramas in small formats. Art critics say the mountain represents Mount Tamalpais, in California, close to where she lived with her longtime partner and sculptor Simone Fattal (also on show at the Boghossian Foundation). (Thibault De Schepper)

In a testament to her love for the mountain, which she defined as “her best friend”, Adnan drew it thousands of times, in ink, watercolour and oil. She even wrote poems about it. “It became her point of reference, her home far from home,” Fattal wrote. But the sun and the coast of Beirut are also quite present in her works. “In Beirut she was in love with the sea,” Fattal says. Despite her many identities - born in Beirut to a Greek mother and an Ottoman officer from Damascus, educated in French, and living most of her life in the US - “Etel was very much an artist of Beirut,” Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury wrote following her death. (Thibault De Schepper)

The exhibition was hosted at the Villa Empain by the Armenian-Lebanese Boghossian Foundation in collaboration with the Pompidou Centre.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.