Meet the Iranians flocking to Turkey for business and pleasure

"You must be crazy to go on vacation inside Iran," 24-year-old Homayoun recalls telling his friends at one of Tehran's famous secret parties.

"Even here in Tehran, if the police come, we have to pay them to let us go," he told them, as young men with fade haircuts and women with heavy make-up clinked small shots of bootleg Aragh Sagi, traditional Iranian liquor.

"But in Istanbul," he told Middle East Eye, "you can party until the morning with no trouble."

'In Tehran, if the police come, we have to pay them to let us go… But in Istanbul, you can party until the morning with no trouble'

- Homayoun, 24, Tehran

Homayoun is one of about four million Iranians who travelled to Turkey last year to escape Iran for a short vacation.

Following the 1979 Islamic revolution, when strict religious code was implemented, Turkey became a prime tourist destination for Iranians.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

And as Turkey's currency crisis worsens, more and more Iranians are making the trip west.

The lira's rapid fall, which began in August 2021, has been brutal on ordinary Turks.

But many of their Iranian neighbours, who have suffered from decades of harsh international sanctions, have seen it as a rare opportunity for a good deal, as the cost of travel, living expenses and foreign investment become increasingly better value.

Tourism heaven

To travel abroad, Iranians have few options. It is almost impossible for them to obtain tourist visas for countries in Europe, the Americas and Australasia. African and Asian countries, too, have rigid controls regarding tourist visas for Iranians. But Turkey is an exception.

For millions of Iranians, Turkey is the first foreign country they visit. For many, it's the only one they will ever see.

Iranians can travel to Turkey and stay there for three months without a visa. There are flights, buses and trains connecting Tehran to Istanbul, where - unlike in Iran - wearing a hijab is not obligatory and drinking alcohol is legal.

These options have made Turkey attractive for Iranians seeking a break from the country's strict Islamic laws.

"Over the past 20 years, Turkey has always been the most popular foreign destination for Iranians," Ameneh Shirkavand, a senior tourism expert at a travel agency in central Tehran, told MEE.

"This destination is now even more attractive because of Turkey's economic crisis. Most Iranians travelling abroad have a very tight budget because the Iranian rial is one of the most worthless currencies in the world. So the weaker the lira becomes, the cheaper this destination is for Iranians," she adds, referring to Iran's currency crisis, which over the past four years has wiped 70 percent off the value of the rial.

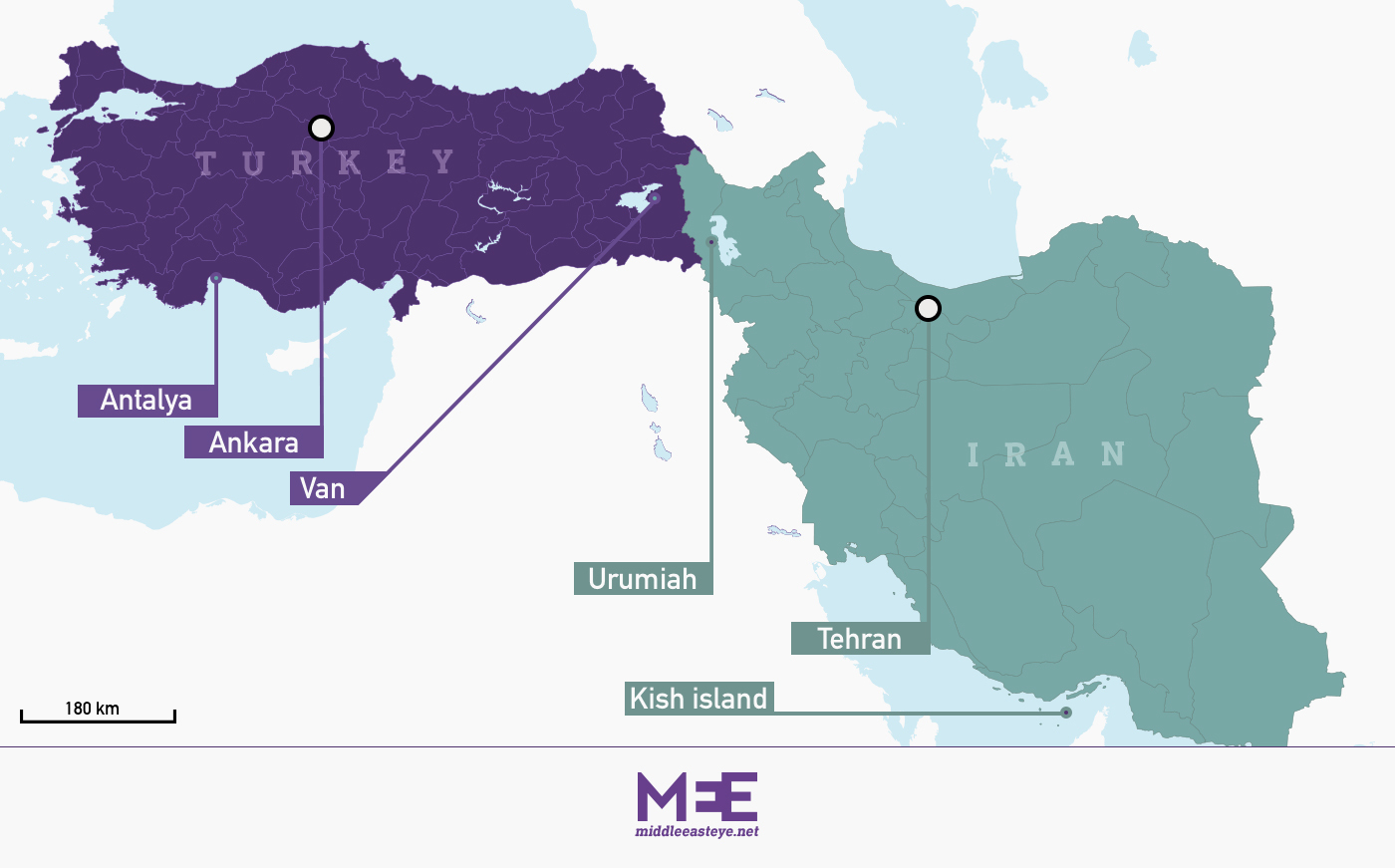

According to Shirkavand, three-day package trips to the eastern Turkish city of Van are now cheaper than travelling to domestic destinations such as Kish island. For example, a three-day journey by bus to Van costs 11m Iranian rials (about $44 on the open market). It would cost Iranians three times more to travel to Kish by plane and stay on the island for three nights.

Explained: Iran's three exchange rates

+ Show - HideIn Iran, foreign currencies have three different exchange rates.

Ordinary Iranians have access to the open market rate, whereby one US dollar is sold for about 250,000 rials.

Then there's the official exchange rate, set by the government at 42,000 rials to the dollar. This is only available to governmental departments and well-connected merchants importing essential goods.

Non-essential goods importers can buy foreign currency with the Nima exchange rate, which is about 220,000 rials to the dollar.

"It's not only the lira crisis that attracts our tourists," says Shirkavand. "Turkey has invested in tourism for over two decades, so all types of facilities are available there. Iran has never taken tourism seriously because of political issues."

But not all Iranians travelling to Turkey seek booze and leisure.

Business opportunities

A decade ago, Van, more than 1,600km from Istanbul, was a quiet backwater.

Now it is bustling, full of Iranians.

Home to a vast lake, Van is the capital of Turkey's most eastern province and only 100km from the Razi border crossing between the two countries.

There is not much to do there, especially during the cold winters, when parts of the lake freeze and snow covers its shores.

But it's the shopping malls and wholesalers that keep the Iranians coming back, many of them purchasing wholesale clothing for their shops back home.

"Ten years ago, I had to go to Istanbul to buy the jeans and leggings I sell in my shop, but now I can buy the same products in Van," says Sudabeh, a 51-year-old shop owner, who only gave her first name.

From her hometown, Urumiah in western Iran, Sudabeh has been travelling to Van twice a year for a decade, sometimes with her husband, other times with her mother, occasionally with both. The more company she has, the more clothing she can back take to Iran.

The tax-free limit for Iranians to bring new products in their luggage is $80 per person, so as the lira loses value, Iranians can take more products across the border.

"Van is much cheaper than Istanbul and much closer to Iran," she explained to MEE. "By travelling to Van, I kill two birds with one stone. I'll have three days of rest in Turkey, and I'll buy the products that I sell in my shop for higher prices."

Free from sanctions

But Turkey offers Iranian businesspeople more than just clothes.

Pressures from US sanctions and Iranian authorities on cryptocurrency traders have driven many of them to Turkey.

In March 2021, Iran's central bank banned cryptocurrency trading and, in October, Joe Biden's US administration warned about the increasing use of cryptocurrencies in Iran, Venezuela and China.

One month later, Mehrdad, a 41-year-old Iranian trader, packed his belongings and moved to the coastal city of Antalya in southern Turkey.

"I was tired of new laws that added more restrictions on trading," Mehrdad, who only gave his first name, explained to MEE over the phone.

US sanctions have disconnected ordinary Iranians from the global banking system and their access to cryptocurrency wallets can easily be blocked.

"In Turkey, I opened a bank account, and now I'm working with fewer problems," Mehrdad said. "I don't know what I can do about my residency after one year, but so far, so good."

The trader, who used to live in one of Tehran's satellite cities, now lives in a shared flat in Antalya, paying about $200 per month, the same as what he paid in Iran. He believes that the price of accommodation in Turkey is another attraction for Iranians who can work remotely or have an income in foreign currencies.

'A simple equation'

Official data shows that since the lira crisis has deepened in 2021, Iranians have also rushed to Turkey to invest in real estate.

Last year, Iranians were the leading foreign buyers of houses in Turkey, with a 21 percent increase in the number of housing units purchased on the previous year. This is despite Iranian authorities' warnings about the risks of investing in Turkey's housing market.

"It doesn't matter what the authorities say since people do not trust them anymore," says Hamid Reza Farahani, an Iranian estate agent in Turkey.

"Since the lira became weaker, more Iranians can afford to buy houses in Turkey, so they brought their money here. And why not, when they don't know what will happen in Iran tomorrow morning?

"Of course, Turkey's economy is troubled. But the situation in Iran is much worse, so it's a simple equation: if you have money, where would you put it?"

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.