A glimpse of life in the Middle East before colonial borders

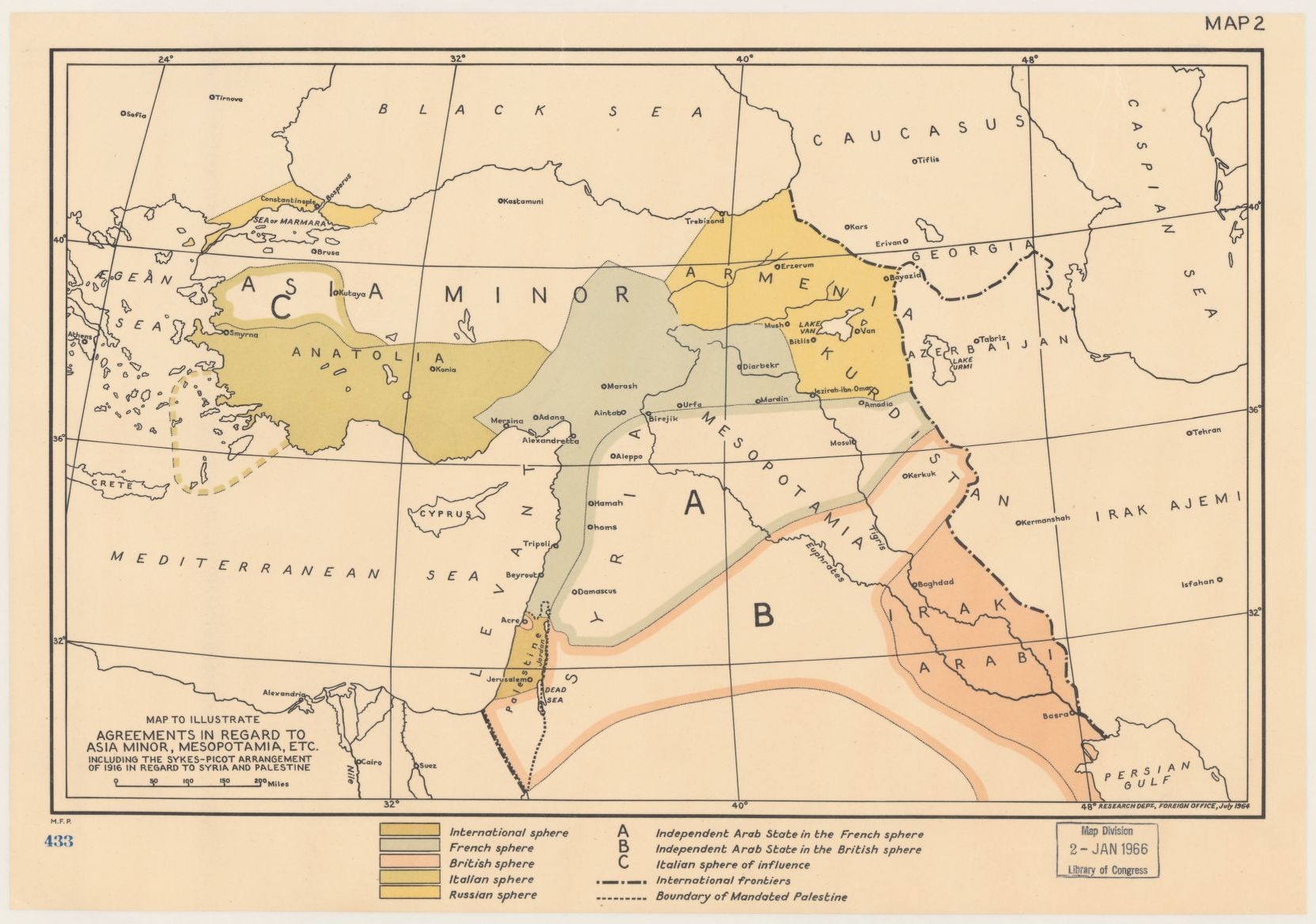

In 1916, the imperial powers of France and Great Britain met in secret to formulate the Sykes-Picot agreement, which would impact the Middle East politically, socially and culturally for ever. Colonial bureaucrats decided that instead of allowing the people of the region the right to self-determination, as initially agreed, they would carve up the Middle East among themselves and begin a process of colonial acquisition under the guise of the Mandate System supported by the League of Nations.

(The top image shows two Arab men in Jerusalem in the 1920s; above is a map of the Middle East divided according to the Sykes-Picot agreement. Both courtesy of the Library of Congress)

In dividing these territories against the wishes of the indigenous people of the Middle East, colonial forces created more than just physical barriers between them - they also transformed the culture of the region's inhabitants, from their sense of identity to their language. Following a few decisions made by people who came from thousands of miles away, the people of the Middle East had new national identities that separated them from neighbours with whom they had shared the wider region and its culture for centuries.

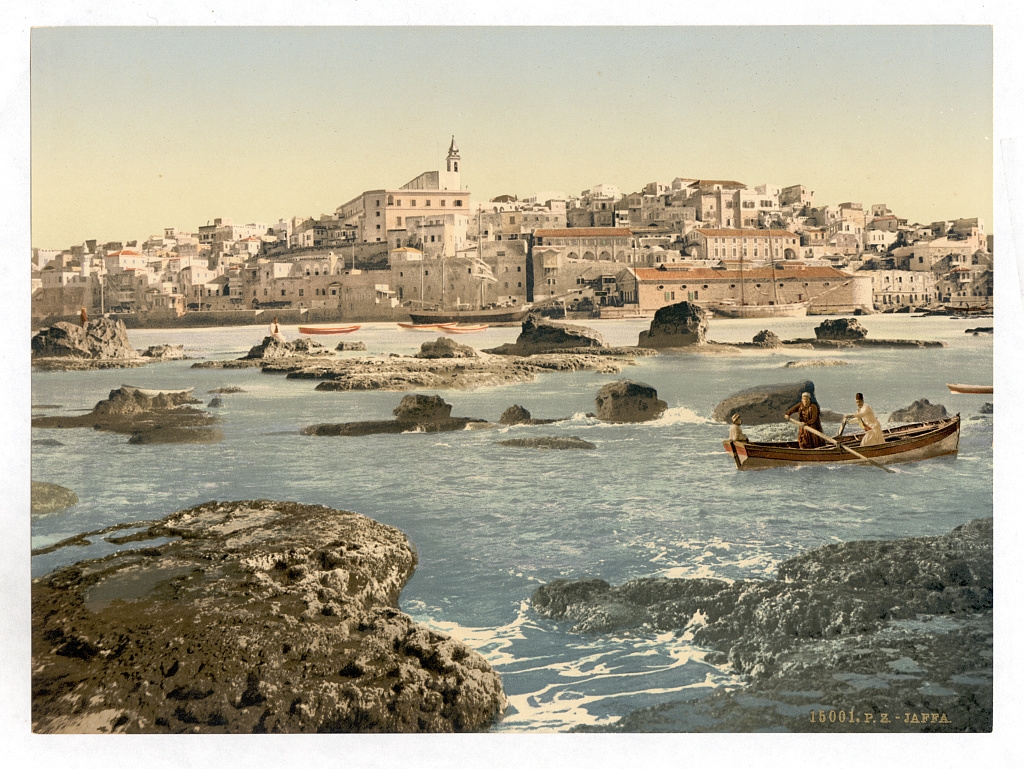

The picture above is a view of Jaffa from the Mediterranean Sea, between 1890 and 1900. While so much of Palestinian and Levantine culture is centred around coastal cities, millions of Palestinians have never been to the Mediterranean Sea, due to the Israeli occupation. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Historical archives provide us with rich materials offering the possibility to reimagine a history those living today never knew; exiled in the ever-growing diaspora, or trapped between fixed artificial borders that have divided them physically for the past century. It is hard to imagine that our reality today is anything like the future envisioned by people living in the Middle East a century ago. Today, the people of the Middle East have less access to each other, an alienation that has resonated since the Sykes-Picot agreement. In today’s world, lines drawn on a map are more divisive than oceans and mountains.

In the photo, a train runs along the Hejaz railway, which was established by the Ottoman Empire and was meant to run from Damascus to Medina, with a branch line to Haifa on the Mediterranean Sea. The railway's construction was halted at the outbreak of the First World War and today the lines are largely out of use. (Library of Congress)

Some older residents of the region have shared stories of their visits to cities such as Haifa, Beirut and Damascus - by road, and all within a day. The restrictions and lack of access between the cities today make such stories seem impossible. Pictured is a bus serving a route between Haifa and Beirut in the 1920s. (National Geographic)

In this picture, taken in the 1930s, passengers wait to board a bus travelling from the Iraqi capital, Baghdad, to the Syrian capital, Damascus. (National Geographic)

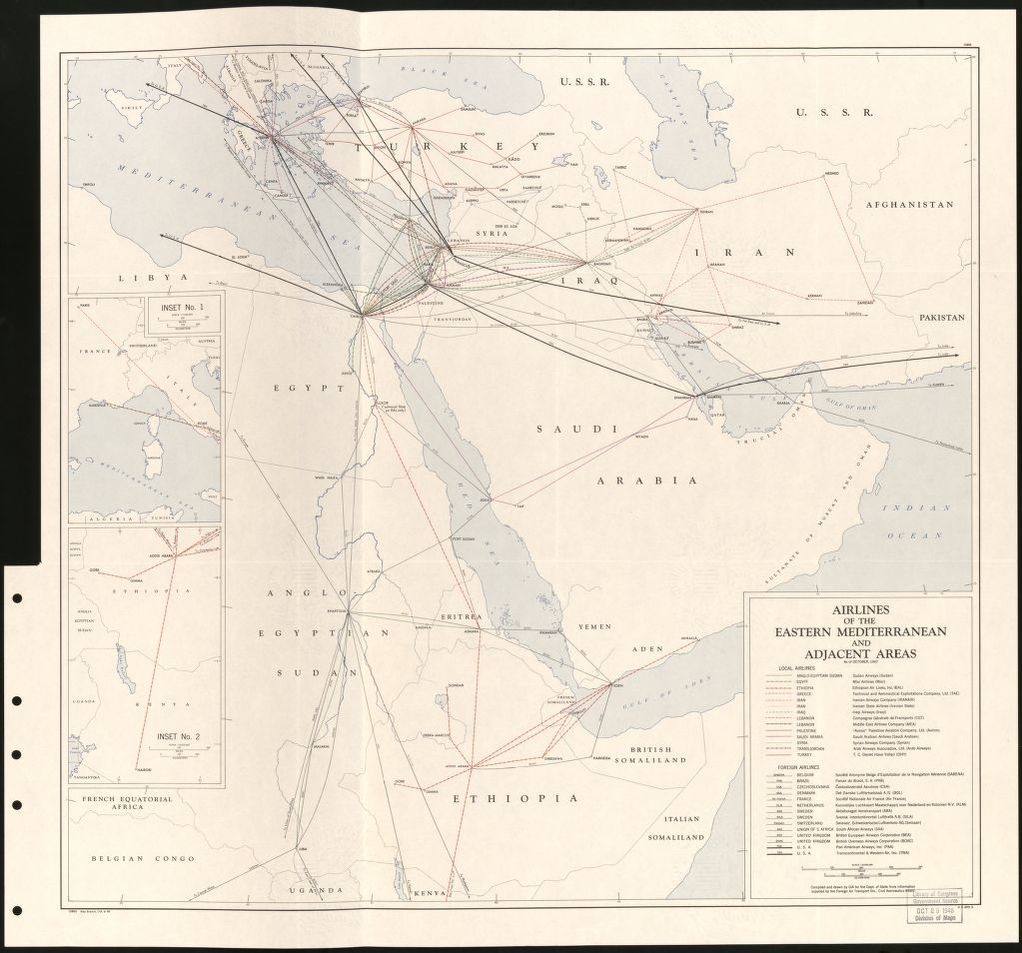

This map shows the air routes between Palestine, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia and beyond in 1947. For many, the thought of booking airlines to travel to neighbouring countries is an action taken with relative ease, but in the Middle East, many citizens have either limited or no access to many neighbouring countries due to strict visa rules. (Library of Congress)

Middle Eastern communities were aware of European colonial ambitions and actively tried to counter the imperial domination of their lands and futures. On 2 July 1919, elected representatives of Lebanon, Syria, Palestine and Iraq met in Damascus to formulate an official memorandum declaring their aspiration to unite the nations of Syria, Palestine and Lebanon under one democratic government.

The memorandum was set to be presented to the American International Commission under the presidency of Woodrow Wilson. The commission spent over a month in the region and heard the petitions of over a thousand people who advocated for a United Syria. Despite these efforts, the commission supported the Mandate System, which divided Syria, Palestine and Lebanon.

Pictured above is a demonstration held in Jaffa in the British Mandate of Palestine in 1919, with a banner that reads: "Palestine is part of Syria". (Source:The Arab Woman and the Palestine Problem by Matiel ET Mogannam, 1937)

In 1917, Ronald Storrs became the military governor of Jerusalem, following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. During the British occupation, a series of very restrictive measures were imposed to control Jerusalem and restructure it according to imperial interests. The notice above was sent out to all residents of the city, mandating that they were no longer allowed to communicate in languages not officially known by the British colonial occupiers. More than 15 languages were spoken throughout the city, exemplifying its unique and immersive culture. The proclamation is one of many examples of how this diverse city was stripped of its cosmopolitan identity through colonialism. (National Geographic)

The man pictured in this 1926 photograph is Sheikh Yacoub Bukhair, head of the Tekkiye Naqshbandi, a Sufi order. Based in Jerusalem, the order was housed at the Zawiyat al Naqshbandi waqf (Islamic endowment) in Sultan Barkuka Street.

Originally built in 1043 CE, the waqf served travellers and pilgrims from the regions of Afghanistan and Uzbekistan. A census of Jerusalem in 1905 found that around 94 people from the region held residency in Jerusalem. In addition to Afghans and Uzbeks, many other groups from across the world lived in Jerusalem. (National Geographic)

Pictured above are students at the Syrian Protestant College, as featured in the National Geographic in 1919. The title of this photograph is “A cosmopolitan Picture from Syria,” as the students photographed are of Syrian, Egyptian, Turkish, Armenian, Greek and Jewish ethnicities.

Frantz Fanon wrote that when writing history, we must do so with the intention of opening the future and fostering hope. Re-examining our history through this perspective can perhaps allow us to envision a future without barriers and isolation. (National Geographic)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Editor's note: The Tekkiye Naqshbandi was housed at the Zawiyat al Naqshbandi waqf not the Zawiyat al Afghani waqf as previously stated

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.