Turkey: Deportation threat dashes Afghans' hope for safety and new life

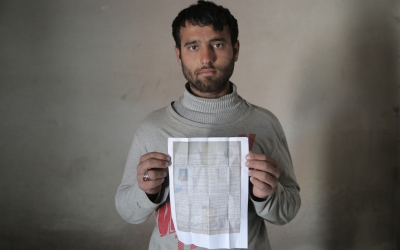

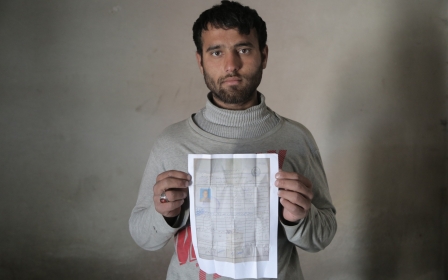

When Jahan Hotkhil left Afghanistan late last winter, his hope was to reach Istanbul to start a new life.

But, like thousands of other Afghans who entered Turkey over the last four years, the 22-year-old never made it to the city which served as the setting for many Turkish soap operas that his family enjoyed watching.

He also had no idea about the growing anti-Afghan sentiment in the country he was heading to.

While Turks were taking to social media to express their increasing resentment towards the nearly four million refugees currently residing in Turkey, Afghans were being sold stories of a Muslim nation where they could escape the war, the Taliban, and the massive economic downturn that followed their return to power last summer.

'We were told they would send us back across the border to Iran, but we had no idea about the deportations'

- Jahan Hotkhil, Afghan refugee

More worryingly, no one had told him that Ankara had restarted deporting Afghans back to their now-Taliban-controlled homeland.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“We were told they would send us back across the border to Iran, but we had no idea about the deportations," Hotkhil told Middle East Eye.

Mahmut Kacan, a lawyer who specialises in human rights and refugee issues, said that since the beginning of the year Turkish authorities had left undocumented Afghans with only two options.

“Those who do not want to return voluntarily are largely pushed back to Iran,” Kacan said.

For Hotkhil, the thought of being sent back to Caldiran, a Turkish district bordering Iran, brought back memories of being trapped in the cold and snow with no support.

“I spent a day and a half trudging through one and a half meters of snow, trying to keep warm," he lamented.

Voluntary return?

Hotkhil said he saw being pushed back into Iran itself as a pretty grim option as well.

For decades, Iranian authorities and residents have been accused of abuse, violence and discrimination against Afghans, even those born and raised in the country. Rights workers also told MEE that unlike the European Union and Turkey - and like neighbouring Pakistan - Iran had never halted deportations of Afghan refugees.

Not during the summer when the Taliban ripped through the nation’s 34 provinces in a matter of 11 days, and not when a series of sanctions, aid cutbacks and withholding of assets by the West led to what the United Nations has called a “downward humanitarian spiral” in the Taliban-run country.

Feeling either outcome would result in his eventual deportation, Hotkhil said he had no choice other than to agree to a so-called "voluntary" return, a practice that has been subject to years of criticism, even well before the Taliban’s return to power.

On 7 April, Hotkhil boarded an Ariana Afghan Airlines flight to Kabul. He said there were more than 200 deportees on the aircraft that night.

Refugee rights workers and lawyers speaking to MEE confirmed that Afghanistan’s national carrier had been operating deportation flights from Istanbul Airport since as early as January.

When his plane arrived at Kabul International Airport early the following morning, Hotkhil said the deportees were left to their own devices, with no one to answer their many questions or help them find their way.

As someone who grew up in the city of Kabul, Hotkhil said he was fortunate as he had a home to return to in the Arzan Qimat neighbourhood - but others were not so lucky.

“There were so many people, even women and children, who were just wandering around the airport unsure of where to go or what to do," he explained.

Hotkhil said the ones from other cities, Mazar-e Sharif and Kunduz in the north and Kandahar in the south, were the most lost, as they lacked the funds to return to their homes.

There was one group that Hotkhil said was especially worried once they landed in Kabul: the former members of the Afghan National Security Forces. He said throughout the flight, the former ANSF members spoke of their fears of being targeted in reprisal attacks from the Taliban, the group they had been fighting against for so long.

Those fears are not without warrant.

Shortly after taking power, the self-proclaimed Islamic Emirate promised a general amnesty for former security forces and government workers, but in many places, that reprieve never panned out.

Investigations by Human Rights Watch and The New York Times have revealed hundreds of cases of disappearances and killings of former soldiers, police officers and intelligence workers by the Taliban in recent months.

'Worse and worse'

When he was held in a deportation centre in Turkey's Erzurum province, Hotkhil said he saw hundreds of other Afghans - including those who had been living in Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir and other cities - who were also awaiting their own deportation.

Saif Afghan was one such person.

The 24-year-old had spent four years working in a leather factory in Tekirdag province. At first, he said his life in the northwestern region was good, as he was able to learn the language and earn up to 4,300 lira a month.

But as the years went on, the odds were increasingly stacked against him and other Afghans, who came to Turkey seeking safety and a reliable income.

'The conditions in Turkey were just getting worse and worse'

- Saif Afghan, Afghan refugee

The last three years have seen a growing resentment of Afghans, as well as other refugee groups, among the Turkish people and employers who are struggling to deal with the effects of the economic downturn in the country.

The precipitous devaluation of the Turkish lira and sky-high inflation, which topped out at 61.4 percent in March, meant that Afghan's 4,300 lira salary wouldn’t stretch nearly as far as it had even a year ago, worth only $290 on current exchange values.

Simply put, life in Turkey was becoming unsustainable for an Afghan refugee.

“The conditions in Turkey were just getting worse and worse,” said Afghan.

So, in March, he got in the back of a truck and headed 321km north to the Bulgarian border. Afghan was caught before he could enter Bulgaria and was immediately sent to a deportation centre.

“I never could have believed that Turkey would send us back to the Taliban,” Afghan said.

But the last few weeks have shown him just how wrong he was. In early April, he heard that a group of more than 120 Afghans had been sent back to Afghanistan. By 16 April, he himself was on a flight back to Afghanistan with 90 other people.

Hotkhil and Afghan said little about the actual voluntary return process, but an 18 April statement from the Izmir Bar Association paints a grim picture that falls in line with what details both men did provide MEE.

According to the statement, on 17 April at least 100 Afghan refugees “were subjected to torture and ill-treatment and forced to sign ‘voluntary return documents’ and their fingerprints were forcibly taken”.

It added that three days prior, on 14 April, representatives from the Afghan consulate were asked to come to the deportation centre and sign for the deportation of those people who did not have passports. This is despite the fact that Ankara does not yet formally recognise the Islamic Emirate as the legitimate government of Afghanistan.

The Izmir lawyers greatly objected to the presence of the consular officers on both legal and moral grounds.

“Even confronting these people with the consular officers under the control of the Taliban is against human rights," read the statement.

Kacan, the human rights lawyer, said the report from Izmir had confirmed what his own clients had told them about their experiences in the deportation centre and the role that consulate workers had played in the process.

The bar association has called for “an immediate end” to such procedures.

They went on to remind the authorities that “those who do not do their duty are responsible for the smallest harm, the smallest damage, and every drop of blood spilled by the people who will be sent back due to this unlawful practice”.

'Even the biggest cities aren’t safe'

Afghan saw the potential harm within a week of his return.

On 20 and 21 April, there were reports of deadly attacks on two schools in Kabul and a mosque in the northern city of Mazar-e Sharif.

“Even the biggest cities aren’t safe,” he said from Kabul.

The attack in Mazar was particularly worrying for Afghan. Not only had he grown up in the city, but the bombing took place only a short distance from a shop owned by his family.

For years, Afghans have been saying that Ankara should not be sending their people back, but even before the Taliban takeover, Turkish officials had been making it known that they had little intention of taking in any more Afghan refugees.

Numbering between 300,000 and 500,000 people, Afghans make up the second-largest refugee population in Turkey after Syrians. But public sentiment has been turning against them for some time.

In fact, both President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) have made very clear statements about their views on any more Afghans coming to Turkey.

In July, as the Taliban was rapidly taking over Afghan districts, the chairman of the CHP, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, posted a video online saying: “The real survival problem of our country is the flood of refugees. Now we are caught in the Afghan flood.”

By the following month Erdogan made his own stance very clear. Speaking only four days after the Taliban takeover, the Turkish president said his country “does not have any obligation whatsoever to be a safe haven for Afghan refugees”.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.