France election 2022: Le Pen holds final rally, Muslims fear for the future

After breaking his Ramadan fast on Wednesday night, Casa sat eating an ice cream in the dark, watching the French presidential debate on his phone. “Macron is chill, more at ease,” said the 25-year-old.

His friends, also congregated by a community centre in a working-class area of Arras, a town of around 40,000 people in France’s northern Pas-de-Calais district, offered their thoughts.

“She got eaten alive, miskina,” said one, using the Arabic for “poor thing”. Like Casa and others Middle East Eye spoke to, he distrusts the media, offering only a pseudonym and refusing to have his photo taken.

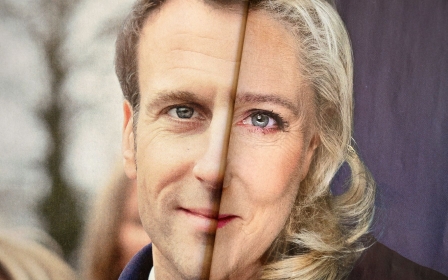

The debate, which pitted centre-right President Emmanuel Macron against far-right politician Marine Le Pen, was the culmination of a French election campaign that has seen the challenger perform better than in previous elections and was within touching distance of the incumbent in an opinion poll between the first and second rounds.

Macron was the most popular candidate in Arras in the first round. But much of Pas-de-Calais, a deindustrialised region that is one of France’s poorest, has become a Le Pen stronghold - at least among those who vote.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

And on Thursday Le Pen arrived in town for the final rally of her long campaign, which had been strong on anti-migrant and anti-Muslim rhetoric.

But the young men interviewed by MEE said they were unfazed by Le Pen’s visit. Leaning on one of their cars, smoking cigarettes, the twenty- and thirtysomethings - some civil servants, others builders - said they voted for hard-left candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon in the first round of the election. For some it was because of his generous economic policies, for others because he has not joined other candidates in slating Muslims.

In the first round, on 10 April, Melenchon was only one point behind Le Pen, whose proposed policies include banning the headscarf in public places and deporting foreigners and undocumented people who commit crimes.

For some in this group, there is little to divide Macron and Le Pen.

“What she says is pretty shocking,” said Mohammed, who spoke carefully, “but Macron’s five years were also shocking, not just for Muslims but for everyone. Under Macron, 650 mosques were closed," he said, referring to an “anti-separatism” law drafted to "free Muslims from the growing grip of radical Islamism", according to Prime Minister Jean Castex. (The actual number is 718.)

Some of the group, as well as others MEE spoke to, said they might abstain in the second round of the election on Sunday. "We wouldn't be voting for a project we like, but for who scares us less,” said Mohammed.

Later, Jamila, 44, who voted for Melenchon in the first round, told MEE she wouldn’t vote in the second, adding that while she was born in France “to them I’ll always be a foreigner”.

During his short election campaign, which has been overshadowed by the conflict in Ukraine, Macron has tried to reposition himself as a benevolent conduit of laicite - France’s hardline brand of secularism, often used to keep Islam out of the public sphere.

In Wednesday night’s debate, he accused Marine Le Pen of stoking a “civil war” by pushing to ban the veil, which she calls “a uniform imposed by Islamists”.

But during his five-year mandate, his government has helped to mainstream far-right talking points about Islam. “Do you know why the veil makes us feel insecure?” he told radio station RMC in April 2018, “because it's not in keeping with our country’s civility, that is to say the relationship between men and women.”

Last year, his interior minister, Gerald Darmanin, accused Le Pen of being “almost a bit soft” on Islam. And in Strasbourg last week, when a young Muslim woman asked Macron if he was a feminist, he responded yes, then asked: “Can I be indiscreet? Do you wear a veil by choice or are you forced to?” Sara El Attar, a Muslim activist, later confronted Macron about the question, calling it “infantilising and patriarchal”.

“It’s become totally banal to criticise the veil, to criticise Islam,” said one of Casa’s friends at the community centre.

That narrative has informed much of the campaign. Far-right polemicist Eric Zemmour, who said that as president he would ban the name Mohammed, announced an “Islam programme” to “reconquer” France.

Both he and right-winger Valerie Pecresse quoted the false “great replacement” conspiracy theory, while Le Pen herself said she plans to amend the constitution to “eradicate Islamism”.

“They went freestyle on Muslims, without any limits, without anyone stopping them,” said Rim-Sarah Alouane, a researcher in comparative law at the Toulouse 1 Capitole University.

“French Muslims just want to live their lives. Go to work, eat, feed their families. Watch Netflix, be normal like everybody else.”

Muslims divided on Macron

But can France afford not to vote for Macron? Analysts and others believe that abstaining Melenchon voters could help Le Pen, who is currently around 15 points behind Macron at the time of writing, scrape to victory. Two in three of Melenchon’s party members have said they won't vote.

For that reason, Casa and most of his group of friends said they will vote Macron. “We can’t let Le Pen get in," he said. "My grandma wears the veil."

'We can’t let Le Pen get in. My grandma wears the veil'

- Casa, voter in Pas-de-Calais

Interviews with 15 or so of the roughly 2,000 Muslim residents of Arras - men and women of all ages - revealed a disconnect between the inflammatory national conversation about Islam in France and their daily reality.

Despite decades of French discourse that suggest Muslims and white France are fundamentally incompatible, none of those interviewed by MEE said there was any hostility between them and their non-Muslim neighbours.

“That’s what the politicians and the media want to spread,” said Mohammed. “The problem with this round [of the election] is they’re stuck on Islam… but we’re forgetting everything that people really need.”

Jamilia added: “It’s the politicians who stir shit up, not normal people. We live together, face to face, there’s no problem.”

Omar Chabani, 70, president of Arras’s el-Feth Mosque, added: “It’s the journalists who create this friction. Every day: Muslims, Muslims, Muslims, headscarf.”

Kaddour Lahouel came from Algeria to France aged 30. Now 72 and the vice-president of the mosque, he said: “When we arrived in this country, we believed everything, we didn’t think it at all possible for a journalist to lie. But little by little we realised."

Aurelien Mondon, a senior lecturer in politics at the University of Bath, says part of France’s obsession with so-called “culture war” issues like migration and Islam comes from a process he calls “cognitive liberation”.

“The more you have legitimate people talking about certain issues, the more these issues become legitimate to talk about. So when you have Jean-Marie Le Pen, with his glass eye, a Holocaust denier, talking about immigration in a racist way, everyone says: ‘This is terrible’.

“But then, when [ex-president] Nicolas Sarkozy says he’s going to get Front National voters one by one because he understands them… It's like: ‘Well, these legitimate people say that, so maybe, maybe I should be worried about immigration.”

Several Muslims in Arras also explained that Le Pen appeals to people they know for reasons other than race. “Most of them aren’t racist,” said Chabani. “They vote for her because life is expensive, they don’t have a job, etc.”

“If Le Pen gets in it’s because people want change,” said Mohammed. “We’ve had all the other parties and nothing has changed.”

According to one pollster, while 43 percent of people who are very satisfied with their lives back Macron, 46 percent who are very dissatisfied choose Le Pen.

Casa said he knows “many people in my entourage” voting for Le Pen because of her stance opposing the Covid-19 vaccine pass, “despite what she says about Muslims”.

Le Pen and the final countdown

Marine Le Pen came to Arras for her final rally on Thursday night. Surrounded by a scrum of security and journalists, face illuminated by the LED lights of television cameras, she entered the vast hangar to chants of "on est chez nous" ("we're in our home"), a refrain she has denied is xenophobic.

Supporters clamoured to get close. "You're in the first row," said one man to another, "kiss her for me."

"I only kiss my wife!" his neighbour joked in response.

Sebastien, 49, a security guard from the southern town of Toulon, held supporters back as Le Pen passed. He has worked for Le Pen and her father, Jean-Marie, since 1993. Are Le Pen voters racist? "Well, my girlfriend is called Leila," he said, "that's all I'll say."

Among the crowd was Ahleme, a 24-year-old Muslim from Arras, who had come to the rally on her own, just to see what it was like. She won’t vote Le Pen in the second round, and said the idea of her in charge was “scary”. She said she was “used to Islamophobia” in France but had decided not to wear a headscarf.

The throng of 4,000 - according to the organisers - broke into the national anthem. When Le Pen mentioned Charles de Gaulle during her speech, one supporter clenched his fists, punched the air and shouted "Vive le general!"

“People of France,” Le Pen boomed, “stand up against those who have so little regard for the defence of our civilisation, who have denigrated your history, your culture, your traditions, who have made migratory submersion our only demographic horizon, who have authorised the construction of mosque-cathedrals subject to the pernicious foreign influences.”

Boos rang out as she finished the sentence, heavy with the language of the “great replacement” conspiracy theory. But the biggest cheer came when Le Pen reiterated her pledge to oppose Macron’s plans to raise the national retirement age.

After the speech ended with another rendition of the national anthem, 18-year-old Madeline stood waiting with her family to catch a glimpse of Le Pen.

She admitted that "with the Islamic veil, she [Le Pen] can be quite extreme," but added: "If someone from another country commits a crime, I find it normal that they're sent back to their country."

Outside, Sandrine, 49, from Calais, wore a National Front badge on her lapel. She said she had voted for the Le Pens since she was 18.

"The veil is a sign of Islamism. Us, it's churches, not mosques."

The future for French Muslims

Aurelien Mondon’s research shows that some of what is attributed to the rise of the far-right is down to several other factors, including the disintegration of France’s centre-left and centre-right parties, as well as the rise in abstentions, all of which have given Le Pen a bigger share of the vote.

But the unchecked violence of the French conversation around Islam still leaves many Muslim Arrageois frightened for the future.

“Me, personally, I don’t suffer,” said Chabani, speaking at the el-Feth Mosque. “We know how it is, but I’m scared for my children, for our children. It wounds them. Their friends are all French, they go to school with them, play football with their neighbours, go to the cafe, the nightclub… that’s where I’m scared for them.”

Opposite him at the table in the imam’s office sat Khaled Diafi, a 70-year-old former mechanic and volunteer at the mosque.

'If she gets in, everyone who said they voted Le Pen but "I’m not racist"… will no longer hide'

- Mohammed, French Muslim

“In 1914-18, in 1939-40 you took our grandparents by force to defend Europe, you knew they were Muslims, you knew they did Ramadan, you knew they didn’t eat pork, it didn’t bother you to take them by force. Now we’re creating problems for you? It revolts me, it’s inhumane.

“Honestly, it’s never happened that someone insults me or comes to my house, but I reckon we’re going to get to that point, so much are these ideas getting into people’s heads. We give them the best of ourselves, and we’re seen as less than nothing. How are we supposed to have confidence in the future?”

Both Chabani and Khaled voted Melenchon in the first round and will vote Macron in the second. In contrast, some Muslims almost want Le Pen to win, to expose what they say are her weaknesses.

“Deep down I think it’s better [Le Pen] gets in, we have five years, the people will realise that it’s pointless, and then we move on,” said one 30-year-old, whose wife doesn’t work because, under French law, she would have to remove her headscarf. “Better that it happens now than our children go through it.”

Marine Le Pen is unlikely to become French president on Sunday. But others worry that a Le Pen victory would legitimise closet racists and cause irrevocable damage.

“If she gets in, everyone who said they voted Le Pen but ‘I’m not racist’… will no longer hide: ‘I don’t like Arabs, I don’t like Black people,’” said Mohammed.

A Le Pen victory would mean her voters saying, “We’ve got the right to do anything,” said Casa. “That could be dangerous for us, our grandparents, our little sisters, for the Muslim community.”

“Macron has two choices if he wins,” said Alouane of Toulouse 1 Capitole University. “Make amends, and have a chance maybe to make things better, or he can keep going on as he is, and if Le Pen is not elected now, she will be next time.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.