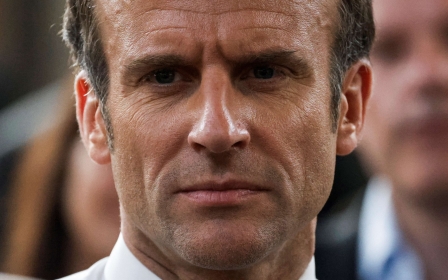

Emmanuel Macron reelection: France is not saved. France is in danger

Those who congratulate France's President Emmanuel Macron on "saving France" from the far right completely miss the point.

It is not "a triumph for democracy” and Macron did not "hold off a far right push", as world leaders and international commentators tend to claim.

Macron has been re-elected with one of the worst scores in the history of the fifth republic - 38.5 percent if we count those who abstained - with millions of voters eventually putting his name on the ballot just to avoid the country being taken over by fascists.

By appearing as the least of two evils, Macron has been successful in posing as an alternative to the far-right, but he certainly did not contradict its agenda

The far right is not defeated and Marine le Pen is stronger than ever, with 13.3 million votes and a historic high score.

So there is not much to celebrate.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Even worse: if Macron numerically defeated Le Pen in securing a second term, he absolutely did not defeat her racist ideology, but rather contributed to its complete normalisation.

By appearing as the least of two evils, the reasonable and presentable version of France’s most cynical breed of politicians, Macron has been successful in posing as an alternative to the far-right, but he certainly did not contradict its agenda, as he came to recognise.

On the contrary, his government has been proud to embrace most of the far right’s demands against Muslims in its infamous "anti-separatism bill", "in order to please the Rassemblement National" and considered Marine Le Pen "'too weak' against Muslims".

Macron has been the one closing down mosques for no valid reason, dissolving human rights NGOs that call for tackling Islamophobia in France, and criminalising the support for the Palestinians.

So why does Macron get a free pass on the international scene? The reasons are simple.

Firstly, he was elected following the election of former US President Donald Trump, so it flows that, in comparison, Macron appears more reasonable. The young, handsome, English-speaking French president who wants to "make the planet great again" made quite an impression.

The farce of an American president did the rest. This allowed Macron to position himself as a pragmatic player in a global game where authoritarians and dictators became the norm.

Secondly, there is still a romanticised vision of what France is supposed to be. As French citizens, we of course play into it by thinking of ourselves as the torchbearers of freedom, which we are not.

This is reinforced by movies and TV series such as Emily in Paris and the like, where racism is invisible and where all the social and political constructs that make up the fabric of our current conversations are absent, leaving Paris as a giant fashion show where baguettes, cheap glasses of wine and long passionate kisses replace police violence, discrimination and headscarf controversies in what France is known for.

And lastly, most of what is organic to French politics gets lost in translation. The perceived complexity and specificity of concepts such as "laicite" and "universalism" make it easy for French elites to paint a picture of the country as a cultural exception and dismiss international criticism altogether as misinformed and threatening.

But it is simple, really: the far right is the leading political force in France. French elites benefit from the stigmatisation and the exclusion of minorities. Laicite is weaponised against Muslims and the government is too busy securing political power to assess and challenge the very structures of racism, which it has thrived upon since the pre-colonial era.

Fascists in 2027?

Now that Macron has secured five more years in power, and no longer has the need to prove to far-right voters that he - too - can harm Muslims, ignore social inequalities and condone police violence, there is a slight chance that he might actually want to be remembered for something else than being the president who led to the election of a fascist candidate in 2027.

This would mean changing Macron's approach to governance, starting to pay attention to what human rights institutions and grassroots organisations have been saying for the past few years. It also means caring about the harm caused to millions of French citizens who have been humiliated, stigmatised and excluded during his first presidency.

So when trying to make sense of what is going on in France, one should look at reports, books and articles which assess what is actually happening, instead of taking for granted the spins and narratives offered by political groups who, while painting Marine Le Pen as the political danger that she is, fail to say they are first and foremost responsible for and beneficiaries of her rise.

France is not saved. France is in danger, now more than ever.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.