From peddlers to presidents: Inside El Salvador’s Palestinian community

In the small Central American nation of El Salvador one can find many visible traces of a place that tens of thousands there call home: Palestine.

Despite being separated by over 12,000km, El Salvador and Palestine share more than a century of history that binds the two countries and their peoples together.

Latin America is home to the largest Palestinian diaspora outside the Arab world, with an estimated 700,000 people of Palestinian heritage residing throughout the region. Roughly 100,000 of them live in El Salvador.

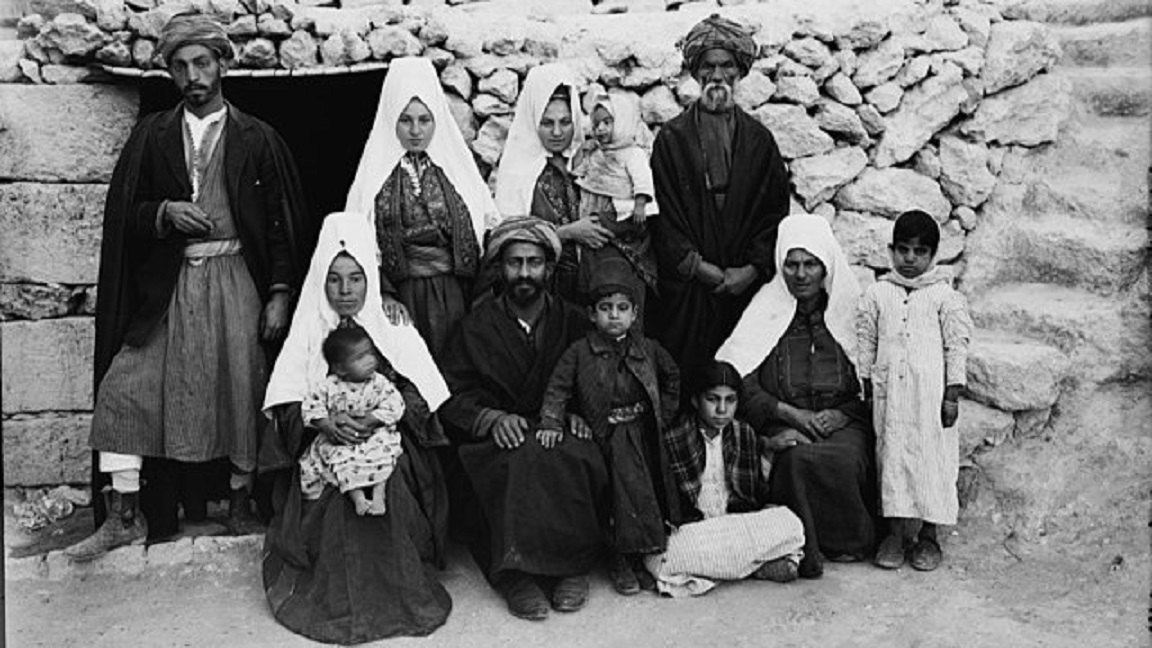

Palestinians first arrived on Salvadoran soil during the late 19th century, as the Ottoman Empire, which occupied much of the Middle East at the time, began to see a significant exodus of its inhabitants.

Between 1860 and 1914, an estimated 1.2 million people fled the Ottoman Empire and resettled in the Americas in search of greener pastures.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Those migrants who first embarked on the transatlantic journey and settled in new countries were predominantly Christians, spurred on by the search for better economic opportunities, as well as a desire to avoid forced military conscriptions as a result of the First World War.

“The reason many Palestinians migrated was the same reason why many people from the Levant migrated at the time: for political and economic reasons,” says Yousef Aljamal, an academic and co-author of Palestinian Diaspora Communities in Latin America and Palestinian Statehood.

“These were the waning days of the Ottoman Empire and the majority of these people were Christians. They did not want to fight in the war alongside the Ottoman Empire and they wanted better lives.”

Only a minority of the first wave of Levantine migrants hailed from modern-day Palestine, yet the vast majority of those that set up shop in El Salvador came predominantly from Bethlehem.

Growing pains

When they first arrived, Palestinians found that they had limited options in their new Central American home. Unlike their European counterparts, they were unable to enjoy prearranged migratory agreements that guaranteed them agricultural work, and as such were forced to find alternative ways of getting by.

Opportunities thus arose on the streets of El Salvador, where many Palestinians began to work as travelling salesmen or peddlers - a common occupation for Levantine migrants at the time.

“Wherever they ended up, Palestinian merchants in Latin America started out peddling goods from door to door - a difficult but lucrative job. Initially, they were selling religious handicrafts," writes Cecilia Baeza, a political scientist and academic focusing on diasporas.

"Very quickly, however, they successfully expanded their business to other manufactured products, and most were able to open up their own shops within a few years.”

When the community first arrived in El Salvador they were officially classified as "Turks" due to their Ottoman origins, as was the case with other Ottoman migrants to the region.

This categorisation however soon took on a pejorative connotation, and the community was subjected to racial discrimination. The Salvadoran elites of European descent - known as "criollos" - had a particular distaste towards the growing community of "Turks".

“Upon their arrival [Palestinians] faced a lot of rejection. The bourgeoisie of El Salvador considered them people of a lower class,” Simaan Khoury, the head of the Palestinian Union of Latin America and member of the Salvadoran Palestinian Association, tells Middle East Eye.

This was reflected at an institutional level. In 1921, a change was made to national immigration laws which classified Chinese and Arab migrants as “pernicious”.

Under the dictatorship of President Maximiliano Hernandez Martinez in the 1930s, strict immigration laws targeting "Turks and other ethnic minorities" were introduced.

In 1933, Martinez enacted a law that prohibited the arrival of Black and Asian migrants, as well as those hailing from Arabia, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine and Turkey.

In 1936, he introduced an additional law banning Arabs from opening any new businesses throughout the country.

“They [Palestinians] were survivors and achieved a lot. They began to work in commerce and soon sparked a revolution,” Khoury says.

Overcoming discrimination

Nonetheless, the Palestinian community was able to overcome the discrimination and institutional neglect and blossom into a thriving community that has helped form modern-day El Salvador.

“It's sad that they had to endure that, but it brings us great pride to know how we’ve gotten to where we are today. Frankly, we have a very good social, economic and political standing,” Khoury adds.

The contemporary development of El Salvador cannot be understood without a smattering of Palestinian and Arabic surnames and families that helped the country grow.

The Nassers, Handals, Simans, Sacas, Safiehs, Zablahs and Bukeles all played a role in shaping the Central American country.

The consolidation of the first wave of Palestinian migration as a generation of salesmen and peddlers allowed those that followed to secure a greater financial foothold, with which they progressed up the economic and social ladder.

Many Palestinian families focused on the textile industry or set up successful storage units, which produced newfound economic wealth. This wealth was reinvested into education in order to bolster future generations’ hopes of social mobility.

“They were empowered economically, their families made sure that they went to school, that they got the education and could now see the fruit of this investment," Aljamal tells MEE. "Many of them are middle class, they're well-to-do economically, politically and culturally.

“They are very empowered because of the kind of jobs their ancestors worked and the racism they endured, and they wanted to change this.”

Palestinian plazas and presidents

Within a few generations after their arrival, Palestinians had become prominent figures in the world of Salvadoran politics, business and medicine.

“Palestinians form an essential part of the fabric of the country," Marwan Jebril Burini, the Palestinian ambassador to El Salvador, tells MEE.

"Those who are of Palestinian origin are in key and important positions in all sectors. They contributed a lot, at all levels, especially economically.

“They are an important engine of the country's economy, but they also contributed a lot politically.”

'Those who are of Palestinian origin are in key and important positions in all sectors'

- Marwan Jebril Burini, Palestinian ambassador to El Salvador

The community’s political strength is demonstrated by the fact that El Salvador’s current president, Nayib Bukele, is of Palestinian heritage.

His grandparents were Christians who hailed from Bethlehem and Jerusalem and resettled in El Salvador in the early 20th century.

“Having a president of Palestinian roots is a great source of pride,” Khoury admits.

However, Bukele is not the country’s first prominent politician with Palestinian roots. In fact, he’s not even the first Salvadoran president of Palestinian origin.

The 2004 presidential election in the Central American country was contested between two Salvadoran-Palestinians: the conservative Antonio Saca and the leftist Schafik Handal, with the former going on to be elected.

When Handal died in 2006, his coffin was draped in the flags of El Salvador and Palestine in homage to his roots.

The social imprint left by the country’s Palestinians can also be seen on the streets of San Salvador, El Salvador's capital city.

In the city, one can find the Villa Palestina housing complex, made up of streets bearing the names of Palestinian cities, as well as Palestine Square and Yasser Arafat Square.

For many Salvadoran-Palestinians such as Khoury, the community’s history, presence and influence in their adoptive home is a long-standing source of pride.

“I’m proud of having Palestinian roots and of being Salvadoran. Without our integration, we wouldn’t be in the position we are in economically, socially and politically,” he says.

This article is part of a series. To find out more about other Middle Eastern communities around the world, stay tuned for the next piece, due to be published next week.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.