Muqtada al-Sadr: How one man assumed so much power in Iraq

On 29 August, the influential Iraqi Shia leader Muqtada al-Sadr announced his "retirement" from the political scene.

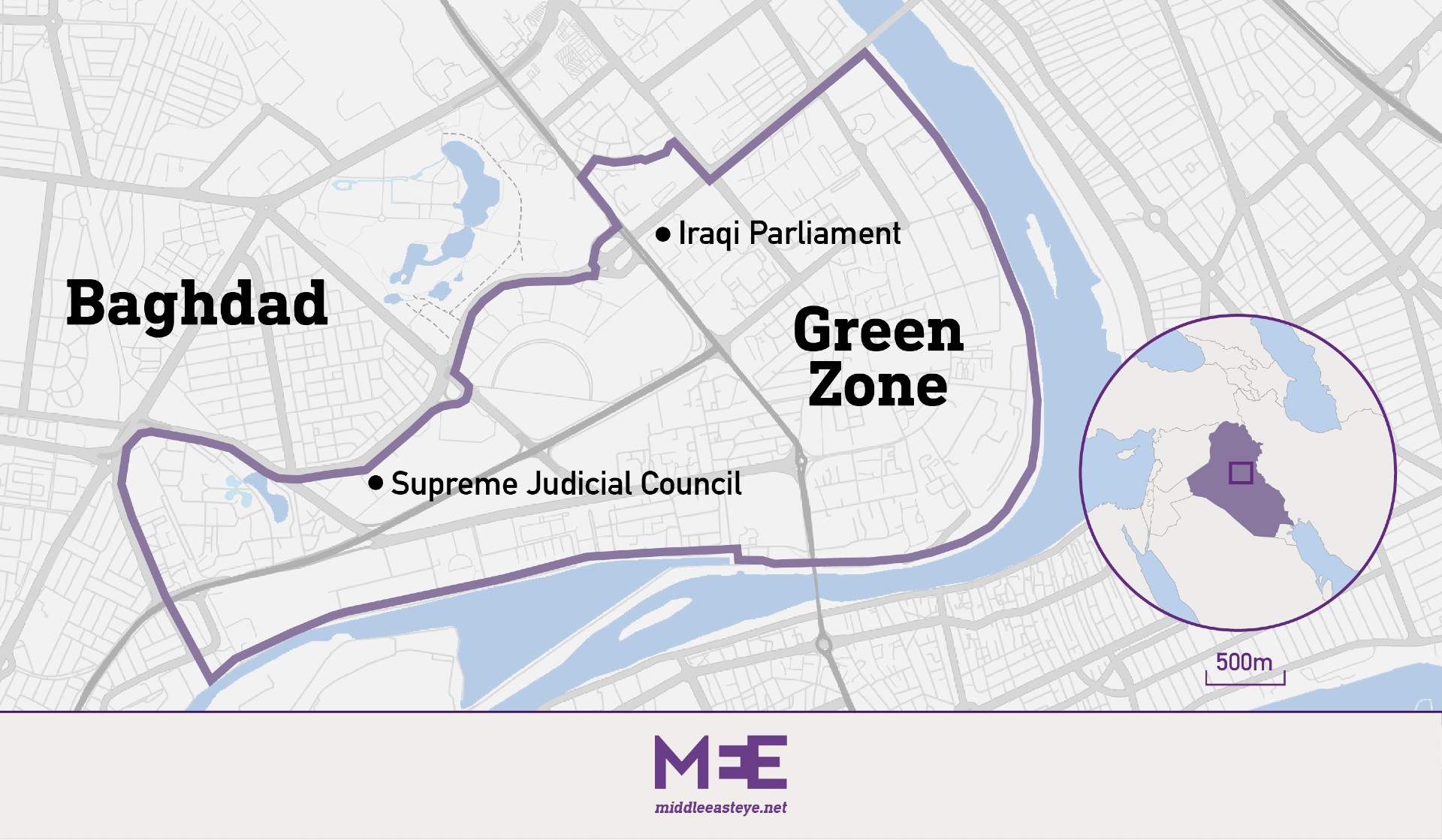

In response, his followers took to Baghdad's supposedly fortified Green Zone and ransacked various government buildings. Regional government buildings across the country were occupied by Sadr's supporters. A countrywide curfew was imposed, security forces and other armed groups got involved and within 24 hours dozens had been killed.

Shortly after midday on 30 August, Sadr gave a press conference urging his followers to end the protests and withdraw from the Green Zone. They promptly did. In response, the curfews were lifted.

Over the space of less than a day, Sadr illustrated once again the power he has to plunge Iraq into chaos and then, with an order, seemingly pull it back from the brink.

The past two decades since the 2003 invasion of Iraq have established Sadr as arguably, with the possible exception of Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the most powerful single individual in Iraq.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Originally the leader of armed forces opposed to the US-led occupation, he has established himself as a nationalist, an opponent of foreign interference and a champion of the poor.

But his ability to mobilise millions of supporters (often armed) with a word unnerves those who see his power as a threat to Iraq's weak democracy and the authority of the state.

Son of martyrs

The 48-year-old Muqtada al-Sadr was born in Najaf during the rule of the Iraqi Baath Party and then vice president Saddam Hussein and president Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr.

Sadr's father, Mohammed Sadiq, and relative and father-in-law, Mohammed Baqir, were both highly influential clerics, and to this day their faces regularly adorn placards and banners of Sadrists and other religious and political factions in Iraq.

Both were killed by Saddam Hussein and are regarded as martyrs and advocates of the poor by many Shia.

Although often referred to by media as a "cleric" with religious authority, Sadr is not a marjaa, religious jurist, like his father and father-in-law were and is not bestowed with the authority to issue religious rulings.

Indeed, the apparent impetus for his decision to announce his retirement was an apparent slight made by Ayatollah Kathem al-Haeri on Monday.

Haeri announced his own retirement from his role as marjaa, a position which he had taken up in succession to Sadr's father and which saw him as one of the main sources of religious authority for Sadr's current followers. Following his retirement, supposedly for health reasons, Haeri told his followers to seek religious authority instead from Iran's supreme ruler, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

He also warned against the divisive rhetoric of those who claimed to follow Mohammed Sadiq and Mohammed Baqir but do not have religious credentials - an implicit slight against Sadr and his claim over the legacy of his relatives.

Despite the lack of religious credentials, however, Sadr was able to capitalise on his heritage and organise the impoverished and marginalised Shia communities of Iraq into a political movement and armed militia (the Mahdi Army) following Saddam's downfall.

The sprawling Sadr City region of Baghdad, named after Sadr's father and previously named Saddam City and Thawra City at various points, has long remained his heartland, but he commands support among Iraqi Shia across the country.

For many years after the overthrow of his erstwhile enemy Saddam, Sadr led his Mahdi Army in an armed rebellion against the coalition forces occupying the country.

He would later reform the Mahdi Army into Saraya al-Salam (Peace Brigades) and become involved in parliamentary politics, calling for an end to corruption, the dismantling of the militias and technocratic reform of the country's economy.

Despite his attempt to portray himself as an opponent of Iraq's establishment, numerous governments have included ministers linked to his movement, while Sadrists are present across the country's institutions.

And while in recent years he has advocated the end of sectarianism in Iraq, in the mid-00s his Mahdi Army was responsible for much of the brutality that swamped the country and saw sectarian killings of Sunnis, Christians and other groups.

Questions still remain about Sadr's involvement in the death of senior cleric Abdul-Majid al-Khoei, who was killed in an attack by an angry mob in the holy city of Najaf in 2003. The US has long suspected Sadr had ordered the killing of a potential rival.

Sadr has also condemned liberalising tendencies in Iraqi society, railing against LGBT people and the mixing of men and women.

His attempts to reinvent himself as a nationalist anti-corruption force in the country led him to throw his weight behind the anti-government movement that began to gain national momentum in 2015.

His followers piled into the movement, which before then was led by secular civil society activists, and, while this added considerable numbers and weight to the situation (leading to an earlier incident of Sadrists breaking into the prime minister's office), many saw it as a hijacking.

A similar problem emerged after the 2019 October uprising. While Sadr and his supporters at first backed the anti-government Tishreen movement, he eventually turned against it and allied with his erstwhile rivals in the pro-Iran camp in suppressing the movement.

The current crisis

His Sairoon party came first in last October's parliamentary elections (though most Iraqis did not vote), and he then attempted to push for the formation of what he called a "majority government" along with Sunni and Kurdish allies.

However, he was unable to secure enough support among other parliamentarians to form a government, and in June, in a supposed attempt to break the deadlock, Sadr ordered his MPs to withdraw from the assembly.

The occupation of the Iraqi parliament, which started on 30 July, nominally came in response to the nomination of Mohammed Shia al-Sudani as a potential prime minister by the Shia Coordination Framework, the alliance of parties that has held sway in the parliament since Sadr's MPs withdrew.

Sudani was a minister in the government of Sadr's arch-rival, Nouri al-Maliki, and saw his nomination as an afront.

In the October 2021 elections, Maliki's State of Law coalition managed to secure the third-highest number of seats in the parliament, and as part of the Coordination Framework he had been looking to make a political comeback.

This has helped stoke tensions with Sadr, who despises Maliki for leading a deadly 2007 crackdown on his Mahdi Army. The problem worsened after the release of a leaked audio tape last month in which Maliki was purportedly heard to describe Sadr as "bloodthirsty" and a "coward" whose political ambitions would destroy Iraq.

Following the leak of the tape, Sadr demanded that Maliki leave politics entirely, and since then the confrontational stance between the two has only worsened, with the former premier being seen brandishing weapons in defiance of Sadr's takeover of the parliament.

'I apologise'

Sadr apologised for the violence on Tuesday, in a speech that drew commendation from the country's prime minister.

"I apologise to the Iraqi people, the only ones affected by the events," Sadr told reporters in Najaf, after giving his followers one hour to leave the Green Zone.

In response, Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi thanked Sadr for his actions in shutting down the violence.

"His Eminence Muqtada Al-Sadr's call to stop violence is the epitome of patriotism and respect to the sanctity of Iraqi blood," he wrote in a statement.

"His speech emplaces national and moral duty upon all to protect Iraq and stop political escalation and violence and, to immediately engage in dialogue."

Whether dialogue will now be possible in Iraq is unsure, but the very fact that the prime minister of Iraq was compelled to commend Sadr for shutting down a conflagration he was largely responsible for is arguably an indication of how much power he has.

For many Iraqis, though, the ongoing violence is simply a fact of life, over which they have virtually no say.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.