Fear, a fatwa, and bloodshed: Inside the battle for Iraq’s Green Zone

Jaafar had spent several nights camped out with other Sadrists in Baghdad’s Green Zone when the ayatollah’s statement came.

Waking up around 11am in one of the protest tents that supporters of Muqtada al-Sadr had erected outside the parliament building, the 36-year-old was shocked to see Ayatollah Kadhim al-Haeri, a hard-line Shia cleric based in Iran’s Qom, accusing Sadr of "dividing the sons of the nation and sect" and questioning the legitimacy of his leadership of the Sadrist movement.

Jaafar asked several friends if the statement could be genuine, whether the ayatollah would really round upon the son of his close friend Mohammed Mohammed Sadiq al-Sadr, and what they believed the younger Sadr would do in response.

Everyone was like him, "confused and waiting for Sadr's response," Jaafar told Middle East Eye.

'We were all nervous. Haeri's statement was a fatwa against us'

- Jaafar, Sadrist protester

Since Mohammed Mohammed Sadiq’s death, Haeri had acted as a spiritual guide for the Sadrist movement based on the father’s recommendation. “He provided us with a kind of protection.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But now that protection seemed abruptly and angrily removed.

"We were all nervous. Haeri's statement was a fatwa against us,” Jaafar recalled.

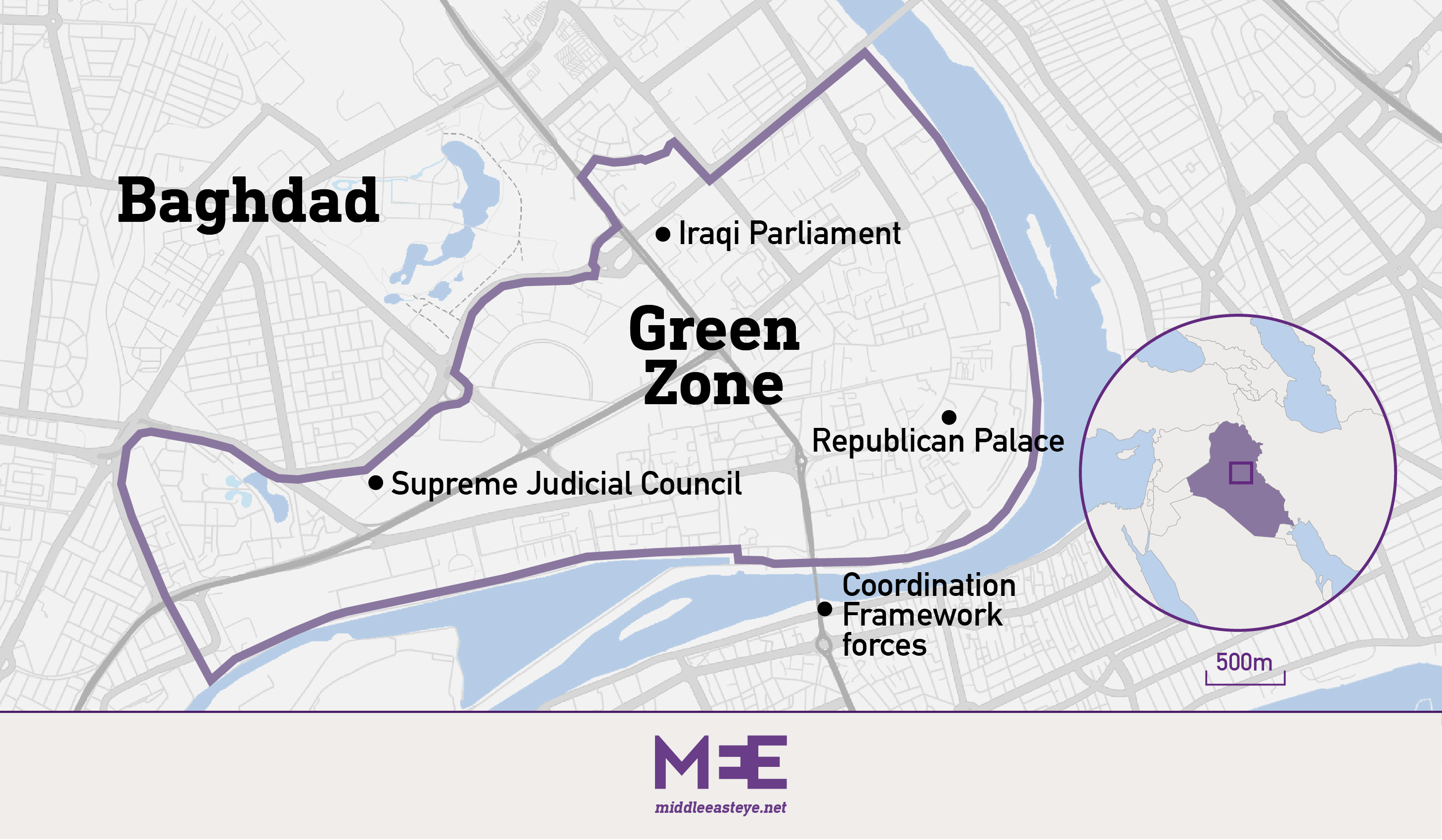

In the days before Haeri’s 29 August intervention, the Green Zone increasingly resembled a war zone.

Escalatory language by Sadr and his Iranian-backed rivals had everyone nervous, and security forces and paramilitary fighters had piled into the fortified neighbourhood.

Sadr’s response to Haeri lit the touchpaper. He suggested the ayatollah’s statement was not written “of his own free will”, but “permanently” announced his retirement from politics nonetheless.

Addressing his followers, Sadr said: "everyone is free from me."

Chaos then erupted. The Sadrists outside parliament, who had camped out there for almost five weeks demanding fresh elections, saw Sadr’s words as a green light to move.

They divided themselves into groups, and proceeded towards the nearby 14 July Square, where they stopped for about an hour, waiting for more people to join them or instructions, several protesters told MEE. Neither arrived.

"No one called us and no one was there to answer our calls. Suddenly everyone disappeared as if they weren't there," Jaafar recalled.

It was up to the protesters to choose their next destination. To their right was the presidential complex and the US embassy. In the other direction was the Republican Palace, where the prime minister conducts much of his work. They chose the Republican Palace.

Security forces in the Green Zone had strict orders not to use their weapons against the demonstrators “no matter what”.

Those around the Republican Palace were no different, a military commander serving in the district told MEE. When the Sadrists decided to occupy the complex and pile into the pool to escape the 50-degree heat, no one stopped them.

Almost an hour and a half passed. There was still no news from the protest organisers.

The leaders of Saraya al-Salam, Sadr’s armed wing, who were responsible for securing the protesters and providing them logistical support, had completely disappeared.

So it was left to Saraya al-Salam’s junior field commanders to lead this unruly mass of a few hundred men.

Around 50 Sadrists were told to stay put at the Republican Palace. The rest continued advancing towards a sit-in by supporters of the Coordination Framework, an alliance of mostly pro-Iran Shia parties opposed to Sadr, who were camped outside the Green Zone as a counter-demonstration.

"This step opened the gates of hell in our faces," said Jaafar.

The Sadrists arrived at the suspension bridge the Coordination Framework forces were based on at 2:45 pm.

Between them were Special Division troops, who started beating the Sadrists in a vain attempt to stop them from crossing the Tigris river.

"They [the Special Division troops] were begging us not to cross. They said that our crossing would mean certain death,” Jaafar said. “We did not listen to them and did not stop.”

At the end of the suspension bridge are the 2-4 metre high concrete barriers that surround the Green Zone.

The Sadrist demonstrators targeted the smaller sections, swarming over the barricades.

Lying in wait were the Coordination Framework supporters, who threw rocks at the advancing Sadrists and beat them with sticks. But they could not force them to retreat, a military commander said.

Suddenly, five armed men appeared from behind the tents. They wore black uniforms, covered their faces with black masks, and carried Kalashnikov assault rifles. They began to fire at the Sadrists climbing over the concrete barriers.

"To be honest, they were not firing at us. If they were firing directly at us, they would have killed a lot of us," said Jaafar, who was on top of one of the barriers at that moment.

As things heated up, the Sadrists decided to go back to the Republican Palace, but they didn't know that their comrades had been expelled and forces were massed there to meet them.

Heavy clouds of tear gas and mace swirled around the area, suffocating many Sadrist protesters, who also came under heavy fire.

Jaafar and his group were trying to figure out what was happening. Suddenly, a large force appeared from the vicinity of the Republican Palace. They also wore black uniforms and masks and moved in three rows.

The fighters of the first row carried batons, while the fighters of the second row brought tear gas and mace, and the third row was armed with rifles.

"They kept advancing towards us. We had gathered from everywhere. Our numbers were hundreds. We begged them. We told them we are Iraqis and you are Iraqis and there is no need for this cruelty, but none of them listened to us," Jaafar recalled.

"They were shooting chilli pepper [mace] and tear gas in the front, back, and middle with strange intensity. They didn't leave us space or time to retreat or withdraw. They acted with malice and hatred," he added.

"I felt despair. I was literally breathing in hot peppers and my eyes didn't stop running without me wiping them off. We were, literally, in the middle of hell."

About 2km separated the palace from the protest camp outside parliament. Sadrist protesters - hungry, thirsty, abandoned, and fearful - told MEE it felt like the longest journey of their lives.

It was now after 6 pm, and the sky over the Green Zone had begun to darken with a hail of bullets and rockets.

The reinforcements that Jaafar and his comrades were waiting for had finally arrived.

The Sadrist counterattack, which lasted for nearly 20 hours, ended with the killing of at least 49 fighters from Saraya al-Salam, three of the faction’s commanders told MEE.

Hundreds of others, both Saraya al-Salam and protesters, were wounded.

“The injuries of most of the fighters were in the head and chest, while the rest were random injuries,” a commander told MEE.

"Most losses were among the unarmed people participating in the sit-in who refused to withdraw. Most of them were killed due to indiscriminate shooting, and some were killed by mistake because they were caught between the two sources of fire."

Iran’s 'back-breaking' strike

When Sadr emerged at 1 pm the next day to give a news conference from his residence in Najaf’s al-Hanana, he looked exhausted and angry.

He ordered his followers to leave their positions, and then minutes later Baghdad began to regain its calm.

The guns fell silent. But questions remained.

Was last week’s violence planned? Were Sadr and his followers attempting a coup? If so, did the Shia cleric blink before he could follow it through? If it wasn’t a coup, then what on earth just happened?

As the streets were swept for bullet casings and shrapnel, no one could even definitely say who was doing the fighting.

The belief of many opponents and allies of Sadr, as well as observers, is that Sadr had been planning to seize the Green Zone for months, but underestimated the military strength of his opponents deployed in the district.

Several of Sadr's opponents told MEE that the Saraya al-Salam commanders had failed to implement the plan, which they claimed included killing Nouri al-Maliki, the former prime minister and Sadr’s arch-enemy, and striking the headquarters of the Hashd al-Shaabi, the paramilitary umbrella group dominated by Coordination Framework forces.

Yet, the course of events narrated by the key characters from both sides of the conflict, as well as eyewitnesses and officials, suggests a completely different story.

In a way, Sadr has long been trying to lead a coup against Iraq’s political system. His bloc emerged as the biggest winner from October’s parliamentary election, and he used this leverage and an alliance with Kurdish and Sunni parties to try and tear up the power-sharing system of government Iraq has followed since 2003.

This would have led to Sadr’s Iran-backed rivals being ousted from power, which they claimed was a conspiracy to hand Iraq to western and Gulf Arab powers.

Yet Sadr’s rivals found a weak spot: the cleric’s arrogance and temper.

“Encouraging him to commit some strategic mistakes was one of the most effective tactics adopted by his Shia rivals," a prominent Coordination Framework leader told MEE.

Sadr’s crowning misstep was to order his MPs to resign in June, followed by the subsequent protests at the parliament building and Supreme Judicial Council.

Meanwhile, he refused all dialogue until his demand for setting a date for new elections had been met.

Iran's intervention was expected at any moment. But no one expected that Haeri “would be the stick that Iran would use to strike Sadr”, a Shia political leader close to Iran told MEE.

The Iranians, the largest regional player in Iraq since 2003, "finally" decided to intervene to "end Sadr and remove him from the political equation once and for all by using Haeri", the leader said.

Haeri was chosen by Sadr’s father to give the cleric and the Sadrists spiritual guidance after Mohammed Mohammed Sadiq was assassinated in 1999.

A number of Shia leaders, including two seminary professors in the holy city of Najaf, told MEE that Haeri's statement was in fact a fatwa that stripped Sadr’s leadership of authority and questioned his faith.

“From the jurisprudential point of view, this fatwa stripped Sadr and his followers of the doctrinal legitimacy that Haeri had secured for them over the last two decades,” one told MEE.

Now Sadr and his followers have the problem of having no religious reference to give them legitimacy, the seminary professor said: “they have to find a quick solution".

The second seminary professor described the fatwa as “harsh and back-breaking for Sadr and his followers”.

However, many seminaries in Najaf agreed that the fatwa has a “political nature”, suggesting that Haeri was pressured to issue it.

Several Shia politicians told MEE that Haeri has been clinically dead for a while. But a number of seminaries who are in contact with Haeri’s brother, who runs his office in Najaf, said the ayatollah is sick, exhausted, and unable to perform his daily work, but still in full mental strength.

It is almost unheard of for a marjaa, the head of a seminary, like Haeri, to resign. The appointments are for life.

"There is no religious example of someone resigning or donating his followers to another. This is not mentioned in the traditions of the Shia seminaries or Shia jurisprudence,” the second seminary professor said.

Though Sadr met Haeri’s fatwa with his withdrawal from politics - something he has promised to do several times before - no one can say what will happen to the Sadrists, who have been cut adrift religiously and told by Haeri to follow Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Haeri’s move was made all the more extraordinary by the hostility that Sadr and many of his followers hold towards Iranian intervention in Iraq. Shia leaders close to Tehran said the instruction to follow Khamenei was what angered the Sadrists the most.

“The Iranians provoked the Sadrists very much with Haeri’s fatwa,” a prominent Shia politician close to Iran told MEE.

“Haeri’s statement was a frank and blatant declaration of war - launched by the Iranians against Sadr,” he added.

"The fatwa is an exclusive area for the clergy, meaning that the intelligence and the Revolutionary Guard cannot play in this area. If this statement was not issued by the office of Khamenei himself, it was issued with his knowledge and approval.”

Who was fighting who?

Though Baghdad has remained relatively quiet since the Sadrist withdrawal, violence did not end elsewhere.

Less than 24 hours later, the situation flared up in Basra, Babylon, and Karbala, where the Sadrists targeted the offices and leaders of Asaib Ahl al-Haq, a pro-Iran armed faction.

They also attacked the presidential palace complex in Basra, where a number of Hashd al-Shaabi fighters are barracked. The attack targeted Asaib Ahl al-Haq fighters exclusively, eyewitnesses and commanders from both sides told MEE.

Four fighters, two from each party, were killed, while a fifth from Saraya al-Salam died the following day from his wounds, security sources told MEE.

Muhammad Salih al-Iraqi, the obscure figure that Sadr uses to communicate his instructions and ideas to his supporters and opponents, on Thursday sent a public message to Qais Khazali, the commander of Asaib Ahl al-Haq: “I warn you, Qais. If you do not rein in your impudent militia and if you do not disavow murderers and criminals or prove that they do not belong to you, you are also impudent.

“Stop disregarding the blood of the people,” it warned.

The Sadrists' anger directed solely at Asaib Ahl al-Haq fighters seemed unjustified at first, but Sadrist leaders told MEE that the faction was one of the most prominent groups that fought the Sadrists in the Green Zone earlier that week.

"They were the ones who killed our sons. We will not allow them to return to their homes. They and their families will be our share," a Sadrist commander in Basra told MEE.

"Let's take our revenge first, then will talk."

Khazali ordered his men to exercise restraint. He also closed all his movement's offices throughout Iraq, until further notice.

Political leaders, commanders and media platforms linked to Asaib Ahl al-Haq denied its fighters, or any other force from the Hashd al-Shaabi, fought the Sadrists in Baghdad.

But three senior Hashd commanders, two of whom participated in the fighting, told MEE that it was the Hashd’s fighters who repelled the Sadrists and prevented the armed Saraya al-Salam troops from entering the Green Zone.

The three commanders said it was the 1,500-fighter-strong brigades linked to Abu Fadak al-Muhammadawi, the Hashd al-Shaabi chief of staff, that had been fighting the whole time.

They said Abu Fadak supervised the battle, under the orders of Faleh al-Fayyad, head of the Hashd.

The three commanders said that most of the leaders of the Iranian-backed factions "agreed to teach Sadr and his followers a lesson" except for three who "categorically refused to participate in the fighting for any reason".

The Badr Organisation, Kataeb Hezbollah, and Harakat Hezbollah Nujaba refused to send any fighters to fight or help repel the Sadrists, one of the commanders, who is close to Abu Fadak, told MEE.

Intervention allegations

Before midnight on Monday, many tried to stop the fighting. But any ceasefire depended entirely on the commanders of Saraya al-Salam and the Sadrist leadership.

On the other side of the conflict, Hashd and other forces were simply trying to repel the Sadrist advance, commanders on both sides said.

Several Iraqi parties asked prominent Sadrist leaders to intervene to persuade Sadr's fighters to cease fire.

Those close to Sadr said that he had begun a hunger strike in response to the violence.

None of the attempts at the time seemed serious, and in truth had little chance of success.

Sadrist leaders came to an agreement at one point to cool the fighting by midnight on Monday, but the arrangement didn't get off the ground.

“The Sadrists were very angry, and it looked as if they had been waiting for this opportunity for years," said one of the Shia political leaders who tried to mediate between the two sides.

The shooting continued until 1 pm on Tuesday and did not stop until seven minutes after Sadr issued an explicit order for his fighters to withdraw.

Sadr's televised speech, which lasted only a few minutes, alluded to an authority that had intervened to force him to retreat.

That opened the door to speculation. Later, Sadr said he had been talking about his intention to retire from politics, which was a response to Haeri’s statement.

But a number of Sadr's followers began promoting the narrative that Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the top Shia religious authority in Iraq, had demanded Sadr stop the fighting.

Some claimed that Sistani threatened to publicly condemn Sadr if he didn’t intervene.

After the shooting stopped, some Iranian-backed leaders thanked Sistani for stepping in. But rather than responding to an actual intervention, they were trying to belittle Sadr and present him as subordinate, several prominent Shia politicians said.

A day later, reports began to circulate that Hassan Nasrallah, head of Lebanon’s Hezbollah movement, was the one who intervened, at the behest of Iran.

In fact, both men did not intervene at all, according to sources close to them.

Sistani did not intervene because it was a political conflict, sources in Najaf told MEE.

Nasrallah did not intervene because he has been at odds with Sadr for years, and the cleric does not trust the Hezbollah leader and would not accept his mediation, sources within the Lebanese movement said.

Regardless, Sadr’s 20 hours of silence as all hell broke loose raises many questions about whether the cleric truly knows the consequences of his moods and actions.

Sadrist leaders told MEE that most people in his movement, including those at the very top, are frustrated and angry, and feel that Sadr has either let them down or manipulated them.

Monday's losses were the result of the lack of coordination, haste, and moodiness prevalent in the Sadrist movement. They were also the consequence of Sadr’s strict subjugation of his leaders, who were unable to independently address mistakes and contain repercussions.

"The situation is very bad. Sadr's mood and his ill-considered decisions will give one victory after another to our opponents," a prominent Sadrist leader told MEE.

"If Sadr does not succeed in containing the repercussions of the recent crisis, the fighting will erupt again within weeks, and this time it will extend to a larger area, and it will be accompanied by dozens of defections."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.