Topoly: Discovering a taste of Tehran in Cuba's Havana

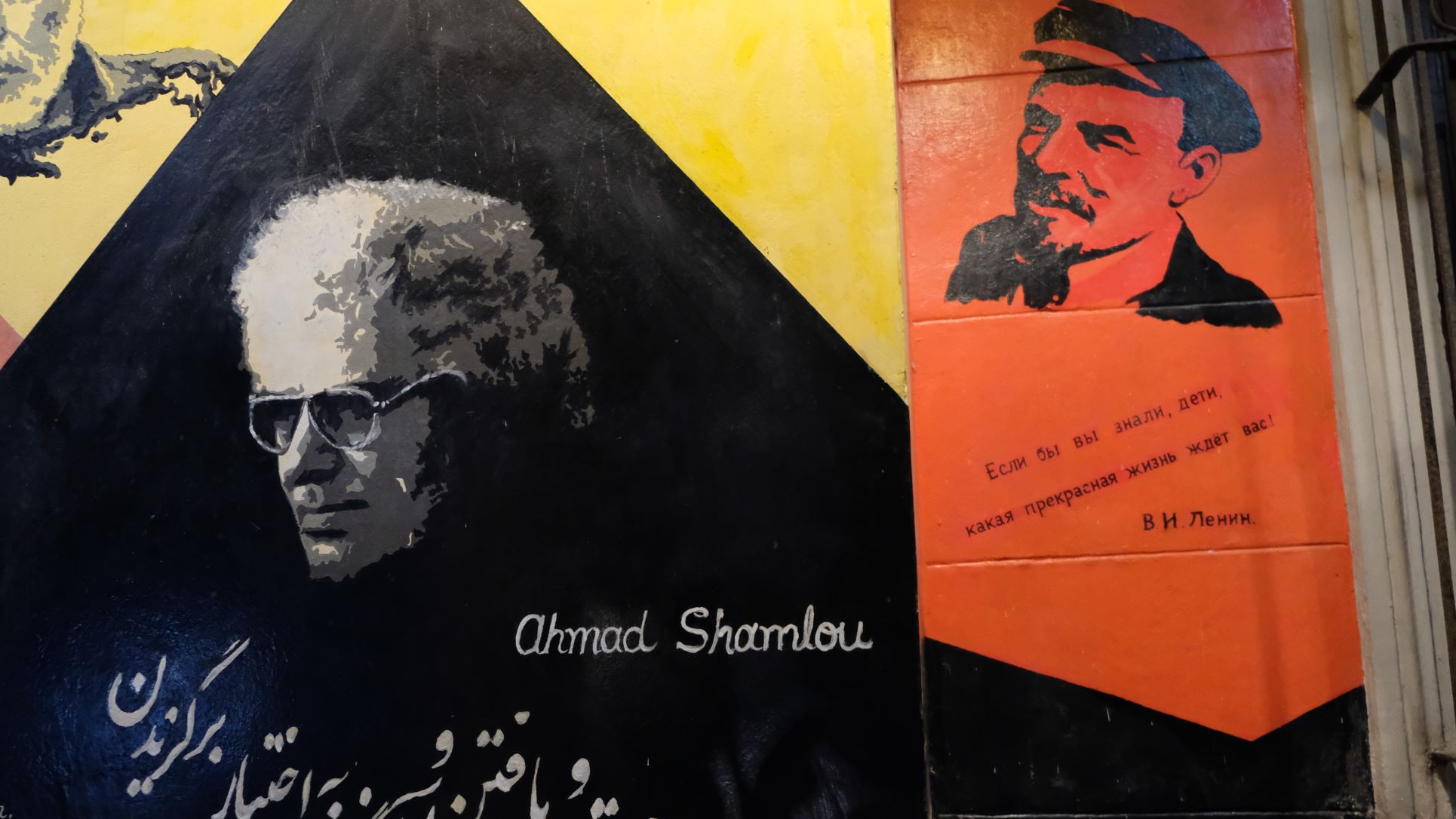

Vladimir Lenin never met the Arab music sensation Umm Kulthum or the Iranian poet Ahmad Shamlou but the three of them hang out together in Havana, painted on the walls of Cuba’s first and only Iranian restaurant.

Iranian-French polymath Farrokh Nourbakht founded Topoly in 2014 as a way to support cultural exchange.

Nourbakht is himself a jack of all trades; he calls himself an interior designer, owns a chain of Middle Eastern restaurants around the world, and acted in A Hero, an Iranian movie that won last year’s Cannes Grand Prix.

'Our two countries have more in common than we think. They are two revolutionary people, very similar in thought and worldview'

- Ali Chegeni, Iranian ambassador

Nourbakht and his restaurant go against the grain in more ways than one. At a time when thousands of Cubans are leaving for better opportunities abroad, Nourbakht has decided to take his chances investing in the Caribbean island.

While diplomatic relations between the two countries are defined by drab official delegations, Topoly tries to nurture Iranian-Cuban ties with food and merriment.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"We’re separate" from the Iranian embassy, Nourbakht says in a mix of Spanish and Persian. "I work for myself, because the restaurant has alcohol and dancers, and they may not like that."

However much Iranian officials may disagree with Nourbakht’s style of business, they have given him a cautious green light, and use his restaurant as a venue for promoting Iranian culture. At the grand opening of the restaurant, Iranian Ambassador Ali Chegeni gave a speech praising the "great role" of artists in consolidating relations.

"Our two countries have more in common than we think," he noted. "They are two revolutionary people, very similar in thought and worldview."

A shared experience of revolution

Although the Cuban and Iranian revolutions happened for quite different reasons - one is socialist, the other theocratic - the countries have had remarkably similar experiences afterwards.

For decades, the United States has attempted to roll back both revolutions with military threats and economic sanctions.

President Barack Obama offered both Havana and Tehran a chance to make amends with Washington, leading to a few years of increased trade and hope for future improvements.

The Democrat's successor, the Republican Donald Trump, condemned diplomacy as weakness and imposed an even harsher economic embargo than before.

Succeeding Trump, the Biden administration has made some moves towards a re-opening with Cuba. That's how I discovered Topoly.

American tourism to Cuba has been banned since the 1960s, as US law forbids spending any money in the Cuban economy.

Then, as part of its outreach to Cuba, the Obama administration allowed an exemption for educational “people-to-people” visits. Trump severely curtailed the programme, and the coronavirus pandemic nearly killed it, but US officials announced in May 2022 that they would be reopening the possibility of group tours.

Given how uncertain the course of US-Cuban relations has been, I jumped at the opportunity, and signed up for the first legal trip I could find.

Then I got a curious Facebook message from an Iranian-American classmate. Since I was in Havana, I should eat at her uncle’s restaurant, she said. It was called Topoly, an affectionate Persian word for a chubby person.

'Go start a restaurant'

The restaurant is located in Vedado, the business district of Havana, about five minutes north of Revolution Square, home to the famous Che Guevara mural.

Topoly is a cosy, perfectly Instagrammable spot, plastered with the same kind of inspirational quotes from literature that can be found in an artsy New York cafe.

But there’s a twist: much of the decor is Marxist or Middle Eastern themed. Next to murals of Marilyn Monroe and Albert Einstein, there’s Che Guevara and Frida Kahlo.

A set of dolls in traditional Iranian garb sits on top of the refrigerator. One of the couches features a carpet with a map of Iran woven into it, each province in a different colour.

And, most importantly, the menu is a mix of Iranian and Cuban flavours. There are tropical fruit cocktails named after Iranian cities. The hot drinks - either tea in the Iranian style or coffee in the Cuban style - come with both Iranian rollet cakes and Spanish flan.

For delivery, the restaurant advertises pizza in the style popular with Cubans, which is to say rubbery-looking.

I had khorak, a traditional Iranian lamb stew, cooked in the style of Cuban ropa vieja, served with avocado and baked beans.

A few weeks later, over the phone, Nourbakht explains the logistics of running an Iranian restaurant in the Caribbean. At the moment, he’s in Tehran; he frequently travels between Cuba, France, and Iran. And despite the shortages in Cuba, he can get his hands on all the important Iranian ingredients but one. We struggle a bit in both Persian and Spanish before I figure out that he’s talking about turmeric.

Nourbakht had been in the restaurant business for over three decades. Topoly began as a chain of Middle Eastern restaurants in France. Surprisingly, they serve Lebanese rather than Iranian food, as according to Nourbakht: “Iranian food is very dry to the French”.

His involvement with Cuba began during the Obama-era boom in tourism. Nourbakht visited first as a tourist, then "took a liking" to the country. He began visiting frequently, organising artistic and cultural events to introduce Cubans to Iranian society.

"Then I decided to stop all this coming-and-going, and just move to Cuba," Nourbakht explains.

"They didn’t give me permission to do cultural work. [Cuban authorities] said, ‘you can’t start up a cultural centre, that’s the embassy’s job.’ I asked what I could do, and they said, ‘go start a restaurant, you can do whatever you want there!’"

'Striver cosmopolitans'

Topoly has hosted live music festivals and dance performances. Nourbakht has also worked with the embassy to host poetry and cinema showcases.

The target audience is Cubans, not Iranians. Nourbakht estimates that there are maybe "ten" Iranians who live on the entire island, as the contacts between the countries are all high-level delegations.

Johns Hopkins University professor Narges Bajoghli, an Iranian-American with relatives in Cuba, has written about Iran’s people-to-people contacts with Latin America.

In revolutionary countries, the people who benefit from the revolution are often “striver cosmopolitans” who feel like they’re playing catch-up with their country’s old westernised bourgeoisie.

It’s that class of people who helped set up Iran’s contacts with Latin American countries, during the populist conservative presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Ahmadinejad’s government went on a diplomatic blitz throughout the developing world in the mid-2000s. Iranian universities welcomed Latin American students, while Iranian delegations visited other countries under US sanctions.

Socialist states like Cuba and Venezuela became off-the-beaten-path opportunities for Iranian investment.

“In Cuba, that’s dried up for several years now,” Bajoghli notes.

It turned out that resource-poor Cuba had little to offer Iran, especially compared to oil-rich Venezuela. Nor is there much room for private investment in a socialist system.

“You can’t just start a supermarket,” Nourbakht points out.

Cultural gap

Today, Bajoghli says, the embassy in Havana is one of the less desirable destinations for young Iranian diplomats. And the Iranians who do end up in Cuba don’t necessarily mingle with the locals.

“There’s a lot of cultural differences, especially with Caribbean nations, not only with drinking and dancing, but also with styles of dress,” Bajoghli says.

Rum is a deeply-rooted part of Cuban culture, including the traditional religious practises of santeria.

'People find a lot of commonalities, and understand the doublespeak that you have to do in revolutionary states'

- Narges Bajoghli, Johns Hopkins University

Revealing clothing, suggestive dancing, and sexual music are in fashion. All of these go against the conservative Islamic morality that the Iranian government has tried to promote, sometimes by force of law.

However, Iranian diplomats or businessmen "who want a different way of doing things" can’t necessarily avail themselves of the opportunities Cuba presents, Bajoghli says.

While she has seen Iranian expats “out drinking all night” in bigger countries, Iranians on official business in Havana "can’t really sneak around, because Cuba is so small".

In other words, it’s not worth it to risk one’s career over a bottle of Havana Club rum. Better to wait for a more exciting post in Europe or Asia.

Nourbakht has a much easier time. He’s a private citizen who came to Cuba as a tourist. And while he works with the Iranian embassy on some cultural events, his livelihood doesn’t depend on either government.

There are other Iranians like Nourbakht, who visited Cuba as tourists and came back with an appreciation for Cuban culture. A few of them founded a Cuba-themed cafe in Karaj, the sister city of Tehran.

Nourbakht was planning to bring Cuban musicians to Iran for a performance, but the coronavirus pandemic put the plans on hold, he says.

The Cubans in Tehran, meanwhile, "mainly stay among themselves, or with other Latin Americans on diplomatic missions to the country," according to Bajoghli.

"They’re not having exchanges with Iranians who are much more open when it comes to alcohol or social issues. They’re building relationships with the people who elected Ahmadinejad."

Despite the cultural gaps, Iranians and Cubans do have a lot to talk about.

"People find a lot of commonalities, and understand the doublespeak that you have to do in revolutionary states," Bajoghli explains. "On the surface, the political or social situation is supposed to look one way, but you know it’s something different."

It's something Nourbakht is certainly familiar with.

The film he played in, A Hero, follows a prisoner named Rahim who accidentally becomes famous by doing a good deed. But the deed turns into a headache for everyone involved, and Nourbakht plays a parole officer, called Salehi, trying to clean up the mess, sometimes with a few white lies.

"You think it's only about what you want?" he says in the film. "The reputation of all of us is at stake."

The film’s director won international accolade for the movie, including the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. Nourbakht, however, stays humble.

"I’m not an actor," he says. "I just had an opportunity."

Editor's note: This article was written before Hurricane Ian hit Cuba and before the ongoing protests in Iran.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.