New Arab movies: The Damned Don't Cry, Hanging Gardens and others to look out for

The awards season could very well be the strangest phenomena in contemporary cinema. Every year, critics complain about the pointlessness of the Oscars race and vow to shun an enterprise that has grown increasingly bloated and inert. Yet come September, at Venice and Toronto, the same critics cannot stop themselves from forecasting potential Oscar contenders whenever a Hollywood film floors them.

As frenzy gives way to fatigue, many non-American films are lost in the shuffle. And we end up with another reaffirmation of the global dominance of the American movie machine.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Such was the malaise of this year’s Venice Film Fest - an exceptionally strong edition nonetheless dominated by US cinema: 10 American productions featured inside the competition alone, and another seven out of competition, including the current American box office champion Don’t Worry Darling.

The result was predictable: American cinema sucked the atmosphere out of everything, directing the coverage of the mainstream press and presenting endless fodder for tabloids.

What was fascinating was the fact Venice was packed with young people this year – not young film buffs but celebrity stalkers, camping on the red carpet in the hunt for footage of the like of Harry Styles and Florence Pugh to boost their TikTok profiles. Star power might not always put bums on seats, but it certainly attracts internet traffic.

Venice was all about clickbait and increasing bandwidth this year. Non-American cinema, by contrast, was relegated to the margins, and the great publicity that filmmakers from around the globe were dreaming of never came.

Toronto was unabashedly Hollywood; non-American films have always had to fight for attention at a festival regarded as a launchpad for the Oscar season.

Both festivals took place at the end of the summer blockbuster season, and the attention afforded to American cinema at both was oppressive.

Theatres, including independent cinemas, have become more reliant on Hollywood offerings to survive

Even more so than in pre-pandemic times, smaller non-American films have struggled to attract a general audience. Theatres, including independent cinemas, have become more reliant on Hollywood offerings to survive.

The global economic crisis and political turmoil are swelling the need for escapist fares – the kind of mindless, disposable cinema Hollywood crafts expertly.

The fear is that, in this cash-strapped world, only Hollywood spectacles are worthy of the cinema release, leaving bold voices from elsewhere to seek their audience in the cluttered space of streaming platforms.

Arab cinema belongs in that latter category, with the Arab selection receiving a tiny fraction of the coverage given to the likes of Blonde or the new Spielberg film. It’s a shame, because many of those pictures offered exciting new perspectives.

The Damned Don’t Cry

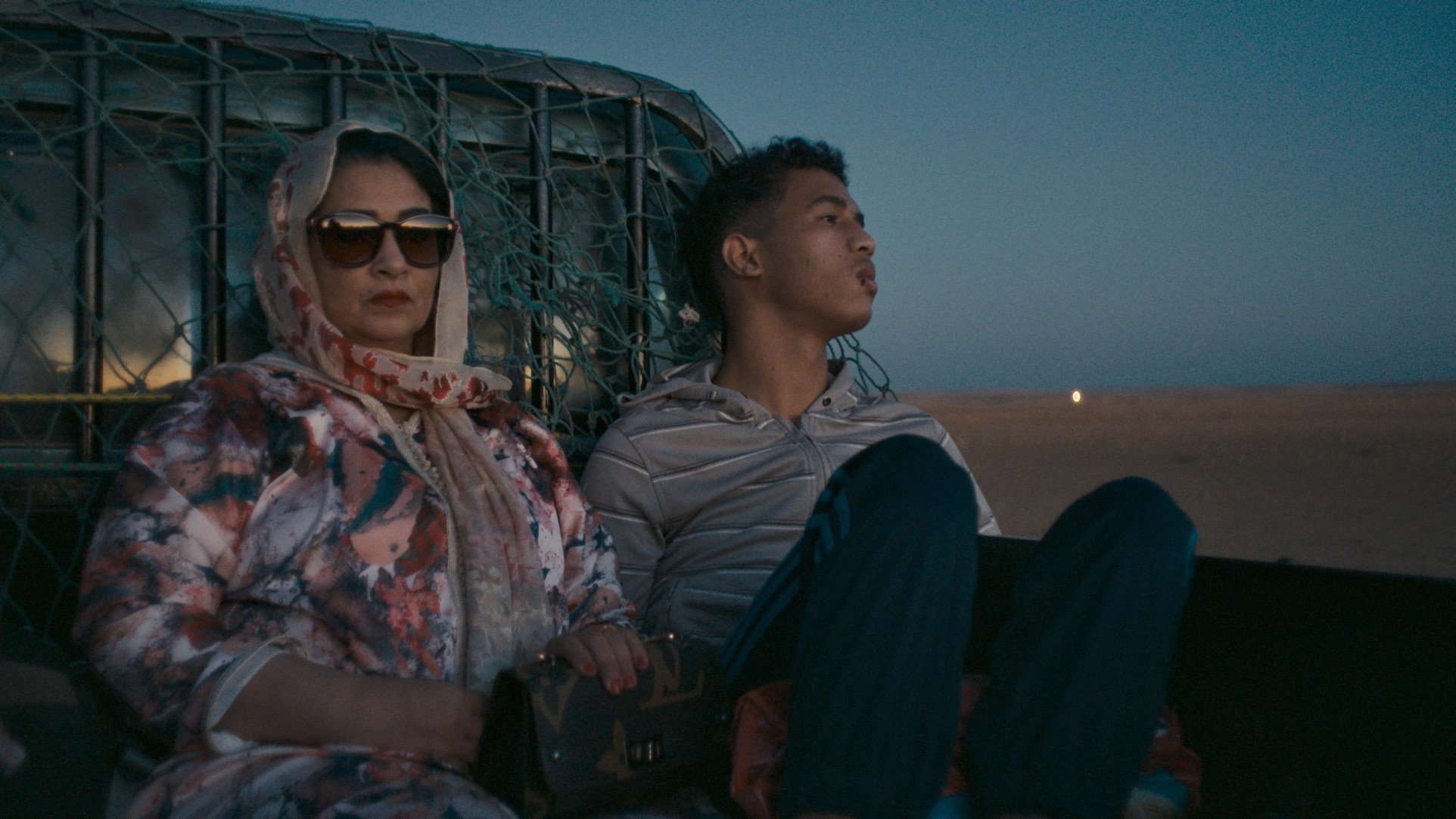

The standout Arab picture at Venice 2022 was The Damned Don't Cry, the second feature of British-Moroccan filmmaker Fyzal Boulifa, who won accolades in 2019 for his debut Lynn + Lucy, which also premiered in Venice.

While Lynn + Lucy was a wholeheartedly British kitchen-sink drama centred on white characters, The Damned Don't Cry is a Moroccan film through and through.

Aicha Tebbae, in one of the most dazzling Arab performances of the year, is vivacious Fatima-Zahra, a former sex worker in Casablanca and a middle-aged mother well past her prime. Yearning for a fresh start where nobody knows her, she moves to Tangier along with her angry, uneducated teenage son, Selim (Abdellah El Hajjouji).

The love-hate relationship between Selim and his mother grows thornier when she shows interest in a pious, married bus driver unaware of her past. Selim, meanwhile, starts to question his sexuality when a setup with an admiring gay Frenchman progresses into a stormy affair.

The Damned Don't Cry is, on the one hand, a story about an atypical mother unapologetic about her past. Fatima-Zahra acknowledges her disadvantaged position in a society where she can never be her real self - a stance that transforms her into a chameleon that can shift to whatever colour men want her to be.

The agency she once enjoyed thanks to her looks has faded, and thus accepting the courtship of a dull man like the bus driver and embracing religion become her way out of a potential life of solitude and economic duress.

The Damned Don't Cry is an intrepid exploration of the mystery that is the Arab mother-son bond

On the other hand, The Damned Don't Cry is a daring come-of-age tale of a sexually confused young man who can only explore his sexuality through servitude or prostitution.

Although sympathetic and initially likeable, the Frenchman who takes in Selim turns out to be afflicted with a neo-colonialist mindset - a civilised face subtly subjugating his young Moroccan lover.

More than anything, The Damned Don't Cry is an intrepid exploration of the mystery that is the Arab mother-son bond. Selim and Fatima-Zahra have a co-dependent relationship typified by years of unshakable resentment and disappointment towards one another.

Like many Arab mothers and sons, the two are not what they want each other to be: Fatima-Zahra is embarrassing to Selim, while Selim is too inconsiderate and unreliable to be the man of the house. Their presence is destructive to one another, yet the two cannot live without each other for long. Boulifa captures this dynamic astutely and maturely.

Not quite revolutionary road

The most remarkable aspect of The Damned Don't Cry is how it breathes new life into melodrama, the genre most associated with Arab cinema.

The same cannot be said of the second Moroccan film at Venice, Yasmine Benkiran’s debut feature Queens, which falls flat in its attempt to tackle the buddy road movie.

Headstrong convicted drug dealer Zineb (Nisrin Erradi) breaks out of prison to save her 11-year-old troublemaker daughter Ines (Rayhan Guaran) from being thrown into a child protection centre.

Accompanied by Ines, Zineb hijacks a truck and forces the hapless mechanic - an unhappy young wife, Asma (Nisrine Benchara) - to drive them to the safety of the distant Atlas region.

The three are tracked down by newly promoted cop Batoul (Jalila Talemsi), who must prove her worth to her facetious elderly partner, Nabil (Hamid Nider).

The shadow of Thelma & Louise looms large over every scene in Queens - a shadow Benkiran fails to escape. Ridley Scott’s iconic picture was revolutionary for giving its women protagonists full agency to reclaim their lives and their womanhood, away from the men who had subjugated them. Scott, along with writer Callie Khouri, did not shy from violence - a tool they deemed indispensable for the emancipation of their heroines.

Benkiran does not go that far, delivering instead a sometimes affecting but ultimately derivative film that does not deviate from familiar North African feminist discourse. Her women are all victims of masculine tyranny, whether husbands, fathers or colleagues.

Daradji's is a dystopian portrait of an abandoned postwar Iraq, a godless wasteland populated by orphan children robbed of their innocence

Zineb, Asma and Ines find solace and courage in each other, while Batoul gains her independence by being single and excelling in her work. The bullish Zineb is the film’s most captivating character - unapologetic in using whatever means to survive in patriarchal Morocco.

Alas, Benkiran cannot conjure up a fitting vehicle for her character, and halfway through it becomes clear that viewers are in for a predictable fare.

While the film is visually striking, in parts thanks to the use of the desert as a liberating no-man’s-land devoid of gender rules, Benkiran does little to nothing with the road movie genre.

A watchable picture that squanders the electrifying possibilities offered by its genre, Queens ultimately suffers from Benkiran’s reluctance to take chances and instead occupy a middle ground free of invention. This is a movie that never takes off.

Death of the American dream

More ambitious is Hanging Gardens, Ahmed Yassin al-Daradji’s debut feature, which made history for being the first Iraqi movie selected for Venice’s official line-up.

Impoverished child As’ad (Hussain Muhammad Jalil) and his 28-year-old brother Taha (Wissam Diyaa) are war orphans who struggle to make ends meet by scavenging among war detritus in the outskirts of Baghdad.

Their relationship begins to fracture when As’ad finds a sex doll apparently left behind by American soldiers.

As’ad develops a fixation with the doll, and before long he sets up a mobile brothel that gradually distorts his hold on reality.

Eerie and unabashedly perverse, Daradji's is a dystopian portrait of an abandoned postwar Iraq; a godless wasteland populated by orphan children robbed of their innocence. Admirably, the filmmaker’s gaze is cold and distant; his approach is more forensic than the typical Iraqi yarn, never descending into sentimentality.

Unlike most recent Iraqi films, Hanging Gardens does not attempt to capture the horrors of the American invasion or its tragic aftermath. Mixing fantasy and heightened reality, it is a rare Iraqi picture dwelling in the wrecked psyches of frustrated young men ignorant of their sexuality and struggling with repressed desires.

It is nonetheless a portrait of the Iraq the US left behind. The American doll replaces the illusionary American dream Iraq never knew; a fantasy sold to a people with nothing to hold on to. Their liberation amounted to endless rubble and perverse fantasies.

Male fantasy and occupation

Equally affecting but cinematically less adventurous is Firas Khoury’s Alam, another debut feature that premiered in Toronto.

The Palestinian coming-of-age story centres on Tamer (Mahmoud Bakri), a high school student torn between the daily chores of being a Palestinian in Israel and his emerging adolescence.

Forced into political apathy by his overprotective father and the occupying Israeli state, Tamer’s dormant existence is shaken when new student Maysaa (Sereen Khass) joins his class. Infatuated, Tamer realises the only way to get close to Maysaa is to join a perilous mission she’s involved in: to replace the Israeli flag on their school’s rooftop with a Palestinian one in the days leading up to the anniversary of the Nakba.

Khoury opens a portal into the little-seen world of young Palestinians in Israel, a world that bears uncanny resemblance to the copious autocracies in the region. Tamer and his friends spend their days drinking, partying and talking of the sex they never have.

In a place where their history and identity is distorted and wiped out, where resistance has proven time and again to be futile, intoxication, be it alcohol, sex or love, is the sole source of comfort.

The flag replacement, a reaction against the revisionist history Tamer and his schoolmates are forced to accept, assumes different meanings through the course of the story: a rebellious exploit, a reaffirmation of robbed identity, a pushback against the occupier, and in the poignant conclusion, an act of self-actualisation.

In the most profound scene of the film, Tamer remembers an uncle telling him that real freedom is not to raise the flag of one’s country… real freedom is to be able to burn it.

Khoury explores these ideas with subtlety and thoughtfulness, underlining the convoluted relationship between the elusive Palestinian nationhood and liberty, between nationalism and self-determination. Unfortunately, these ideas are undermined by a lethargic drama and tepid filmmaking.

Alam suffers from a sluggish tempo, dragged down by excessive exposition and the unconvincing courtship between Tamer and Maysaa. Deficient in both charisma and soulfulness, it’s difficult to see what the striking Maysaa sees in Tamer. For his part, Tamer’s introspective journey is more genuine and stirring than his puppy romance, which often feels little more than male fantasy.

Cinematically, Alam is visually flat, save for a few scattered moments: Khoury implements a literal translation of his story, adopting no visual point of view to the material at hand.

He does toy with the conventions of the high-school drama by framing his coming-of-age story within the uniquely Palestinian context, but fails to find an engaging visual language to capture the frustrations and the dreaminess of teenage life.

Despite its shortcomings, Alam remains essential viewing, if not the transcendant cinematic experience it could have been.

The Damned Don’t Cry is screening at the London Film Festival from 5 October. Alam is showing at Rome Film Festival’s official competition from 13 October.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.